Information and resources for adapting to climate change.

Empowering Farmers as Conservation Leaders

Our Most Memorable Maps and Graphics from 2018

Q&A: How Will Snohomish Farms Endure Climate Change?

A New Tool for Farmers in a Changing Climate

How Safe is Your Home?

Nooksack Levee Project Shows Success of Floodplains by Design

Two-Minute Takeaway: What is an Atmospheric River?

On moving ground in the Skagit Valley: observing sediment and climate change

Written by Jenny Baker

Senior restoration manager for The Nature Conservancy in Washington, based in Mount Vernon

Most of my time is spent on projects where I see both river and tidal processes at work moving sediment toward what I call the "big pond" of Puget Sound. When moving water gets close to that big pond, the sediment settles out in the lowest parts of river channels and out across marshes and beaches.

We've had several major storms this winter that have given me a glimpse of how sediment movement will change with climate change — it is estimated that bigger and more frequent floods in the Skagit River could carry three to six times more sediment toward Puget Sound. At the same time, sea-level rise will move the edge of Puget Sound — and the zone where sediment settles — farther up river channels.

And we may already be seeing this in the Skagit Valley. Eric Grossman, a scientist from the U.S. Geological Survey, has looked at how the river bed has changed over the last 35 years. He found that a lot of sediment has settled and the river bed has gotten shallower. Below is a graph showing that the depth of the river bed at a location near Mount Vernon has gotten shallower by almost 10 feet between 1975 and 2012 (the lower portions of the graph is the river bed).

This has ramifications for how much room there is for water to flow through the river channel and out into Puget Sound — sediment deposited farther upriver means less room for floodwater before it spills out into homes, businesses and farms. And sea-level rise adds to the impacts communities experience as higher tides back the rivers up into shallower channels. Dikes and levees along rivers were built for historic sea levels and river flows. But we're seeing already water spilling over dikes close to Puget Sound. Below is a photo of a dike on Fir Island during a storm in March.

Most might not think about changes in sediment being associated climate-change impacts, such as flooding. But as I am learning, changes in the amount of sediment that comes down rivers and settles out can be a major contributor to climate-change impacts in communities located near lowland rivers. Expect to hear more about sediment and climate change impacts in the future.

A River Revolution: From 0 to 56 in four years

Written by Bob Carey, Strategic Partnerships Director

Maps by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

Floodplains by Design, a public-private partnership aimed at revolutionizing river management across Washington, came together in 2012 with the goal of making our communities safer and rivers healthier. It started as a concept: get the leaders of programs and interest groups that influence coastal and riverine floodplains out of their silos, have them work together to figure out how to manage these landscape in a collaborative, integrated fashion, and we’ll collectively do a better job of delivering society’s goals of reduced flooding, stronger salmon runs, clean water, economic development and a high quality of life.

Floodplain managers of various sorts – county flood managers, tribal fisheries biologists, agricultural drainage districts, conservationists, etc. – embraced the concept, having seen the folly of trying to “control rivers” and the inefficiency of trying to manage only one cog in a complex social and environmental landscape. In 4 short years the concept has evolved into a broad partnership – a “movement” in the words of one local partner. The “movement” has benefitted from strong support from the state legislature which has given $80M to the Washington Department of Ecology for the new state Floodplains by Design grant program.

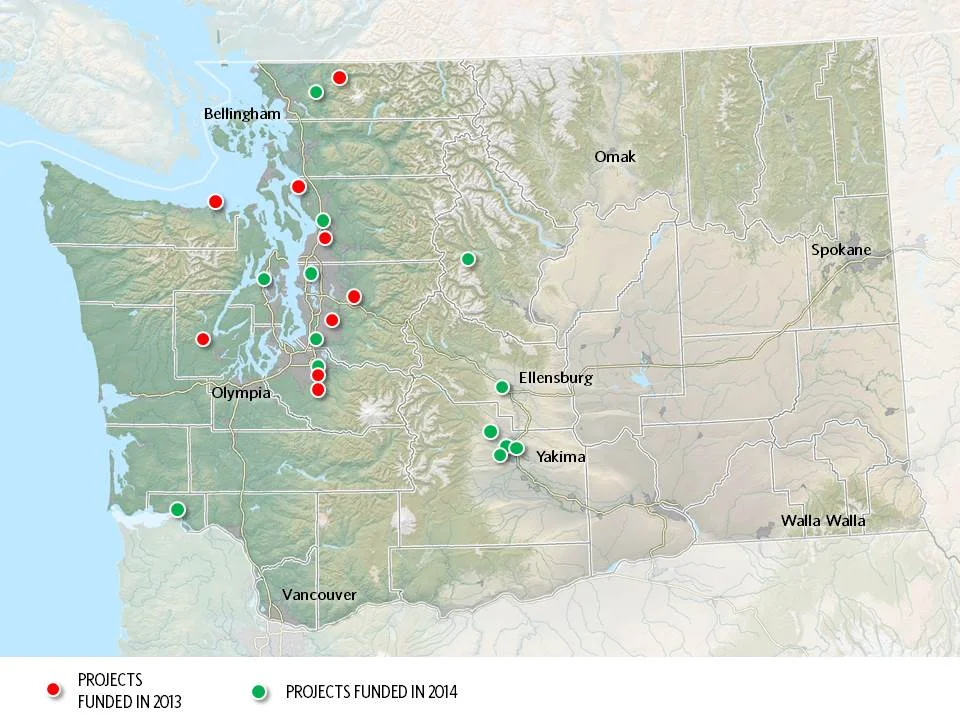

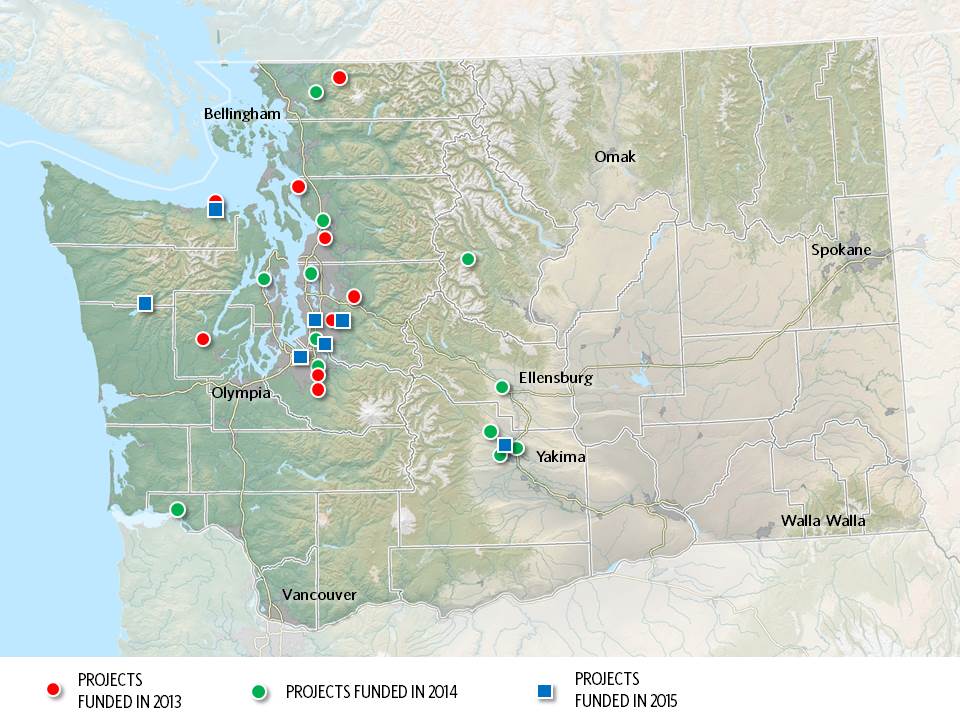

Erica Simek Sloniker, Cartographer and Visual Communications specialist for The Nature Conservancy, has produced a map series that documents the evolution from concept to movement. The initial 9 Floodplains by Design demonstration projects were funded by the state legislature in 2013. 2014 brought 13 more and 2015 another 7. Earlier this year, the Department of Ecology received 56 proposals for the next round of funding – an indication of the strong interest in joining this river revolution.

For more information visit www.floodplainsbydesign.org .

Floodplains: Revisited

Written & Photographed by Robin Stanton, Media Relations Manager

I revisited two Floodplains by Designs sites on the Puyallup River – the Calistoga Reach project in the town of Orting, and the South Fork project a few miles north and downriver from there.

These were both projects designed to re-connect the Puyallup River with its historic floodplain, provide more salmon habitat, and reduce the threat of flooding to people.

The Calistoga Reach project was completed in November of 2014—a week later the river hit a flood stage that previously had sent thousands of people fleeing from their homes. This time, Building Official Ken Wolfe said, “We didn’t have to deploy even one sandbag.” The river rose again in 2015, and again the town stayed dry.

Today, you can see the reclaimed natural areas that in times of flood give the river room to rise, and also offer refuge to juvenile salmon and other wildlife and walking paths for people.

The South Fork project is a new side channel for the river, again giving the water places to go when the volume is high, along with great salmon habitat. It’s being completed in stages, and by the time it’s finished, it will be a mile-long side channel, the longest on the Puyallup River. Engineers Jeffrey Davidson and David Davis helped me scramble all over the site, Pointing out new channels created by the river, engineered logjams that are evolving as the river runs through, and new gravel bars and sediment deposits brought down from Mount Rainier by the power of the river. Salmon are using the site, and they’ve seen black bear and deer out there as well.

It's remarkable to see how nature can come back and revive when you give it a chance!

Act Locally, Share Globally

Written by Bob Carey, Strategic Partnerships Director

Photographs by Flickr Creative Commons

Just a few short hours north of Seattle and set in the vast beauty of British Columbia, the Conservancy's Floodplains by Design program was the featured topic at a Canadian Water Resource Association workshop in Surrey. More than 30 WATER resource management leaders overwhelmingly responded positively when, at the close, their president asked if they were inspired by this work happening just south of the border. Their response was just as positive when asked if they’d like to see such a program in British Colombia and on the Fraser River.

The gathering of representatives from BC’s major cities, the BC government, the Fraser River Basin Council and environmental and academic groups represent those on the forefront of managing the Fraser River – the largest river in both BC and the Salish Sea, and the watershed with the highest flood risks in Canada. The strong affirmation that the “Floodplains by Design” approach makes sense and is applicable across the border made me proud to be part of a team leading the charge in making the region’s rivers more resilient for people and nature.

Restoring nature to address societies most pressing challenges is a prominent theme in the Conservancy's global conservation agenda. Our Floodplains by Design work in Washington is one of the best success stories of accomplishing this at a meaningful scale. Having secured $80M in new funding and helped catalyze 30 projects across the state, in which the restoration of nature and reduction of community risks are being pursued hand-in-hand, it’s clear that the approach can deliver tangible benefits to people and nature. That is why the invitations to share our story are numerous.

In addition to myriad audiences in Washington, over the last couple years our WATER team members have shared the Floodplains by Design story with a variety of national and international audiences, including: China Coastal Wetland Conservation Network (China), Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference (Vancouver, BC), American Planning Association (Phoenix), Association of State Floodplain Managers (Atlanta, Seattle), National Academy of Sciences (Washington DC), North American Water Learning Exchange (Pensacola, Phoenix) and the NW Floodplain Management Association (Post Falls, ID).

There are many great things about working for The Nature Conservancy, among them – the ability to innovate, the ability to scale up our work, and the ability to export beyond our borders.

It’s a recipe for making real change in the world.

Floodplain Restoration along the Olympic Discovery Trail

A win-win project for people, nature and our treasured salmon

Written by Jenny Baker, Senior Restoration Manager, and Photographed by Julie Morse, Regional Ecologist

When a popular recreational trail on the Olympic Peninsula was damaged by a flood and closed last February, there were two options: either 1) fix the trail for walkers and bikers, or 2) fix the trail for walkers and bikers AND do it in a way that improved fish habitat and reduced flood risk. The choice was obvious: build a project with many positive outcomes.

The Olympic Discovery Trail is a rails-to-trails system that currently extends from Discovery Bay to Port Angeles and receives 100,000 visits per year. When a portion of the trail over the Dungeness River near Sequim was damaged, walkers and bikers were anxious to get it fixed quickly. Randy Johnson, Habitat Program Manager with the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, saw a great opportunity for a win-win-win project, but he had to act fast to make sure the project could incorporate benefits to fish and flooding, and get the trail back in use.

The damaged section was part of a 585-foot-long trestle supported by creosote pile structures every 16 feet across the floodplain. Fill had been placed across an additional 165 feet of floodplain to meet the pile-supported trestle. These structures caused a major blockage, wracking up wood, blocking flood flows and requiring that the river be “trained” to go under a bridge. This essentially forced the river into one place and cut it off from the floodplain. Healthy rivers move around in their floodplains, creating vital habitat for fish, storing floodwater and keeping people nearby safe. These processes had been severely limited by the trestle and fill.

Because the project had several positive outcomes and support from various stakeholders, it moved forward quickly. Using funding from Floodplains by Design, Salmon Recovery Funding Board, Bureau of Indian Affairs Climate Adaptation fund and other sources, the design was completed, permits were obtained and construction was underway before the end of August. By early October, the old pilings had been removed and new footings to support a just a few concrete posts - 180 feet apart instead of 16 feet apart - were being constructed.

By December 2015 the reconstructed trail will be completed, allowing the river access to an additional 750-foot-wide floodplain. Recreational trail users will be able to get back on the trail. Viewing platforms will allow groups of students and birders to gather out of the way of walkers and bikers, and take in the river and its wilder inhabitants.

This year there has been a large number of pink salmon returning to the Dungeness River to spawn. When we toured the project site in early October, the river was alive with fish hovering over their redds. As an avid biker myself, I love that there are trails like this where I can look down and see salmon spawning.

The Olympic peninsula provides critical habitat for several species of threatened salmon. The last few years have seen some big restoration projects completed, between JimmyComeLately, the Elwha River Dam removals, and now several projects along the Dungeness River and estuary. It’s inspiring to see the impact these big projects are having on restoring salmon habitat.

Welcome to Flood Season

Written by Julie Morse, Regional Ecologist, The Nature Conservancy in Washington

Photogrpah by Andy Porter, Northwest Photographer

It’s flood season here in Western Washington. That’s nothing new of course. Puget Sound rivers have reached flood stage over 1400 times in the last 20 years. It’s just part of life here.

Albeit, a very stressful part of life. Especially for floodplain managers whose jobs it is to minimize the damage caused by swelling rivers that naturally want and need to jump their banks – wreaking havoc on people’s homes and businesses, undermining transportation corridors, and putting lives and our economy at risk.

Ken Wolfe has one of those unenviable floodplain manager jobs. He is responsible for safety of the City of Orting which sits on the Puyallup River -one of the most flood prone rivers in the State. So it’s strange to see him walking around with a big smile on his face this time of year.

Last week a “pineapple express” or what the weathermen call an “atmospheric river” moved through our region bringing heavy rains. These storms are common here and can result in flooding, especially in the fall when there’s little snowpack in the mountains to absorb all that rain or when it warms rapidly after snowfall so rain and snow melt create a double whammy. The Puyallup River was raging and peaked at over 16,000 cubic feet per second.

The last time the river got that high was in January 2009, when it broke through the levee and caused 26,000 people to be evacuated in the Puyallup River Valley, in and around the City of Orting It resulted in one of largest urban evacuations in the State’s history. Despite the fact that it was the 4th highest flow ever recorded on the Puyallup, this year only a handful of residents voluntarily evacuated.

And instead of overseeing the chaos of filling 17,000 sandbags as he did in 2009, Ken Wolfe is smiling.

Just last month major phases of the Calistoga Reach Floodplains by Design Project was completed.

In Orting, the City moved 1.5 miles of the levee back to expand the width of the river corridor by up to 4 times - giving the river more room to spread out and slow down. Clearly, it worked, and has helped dramatically reduce the flood risk for this community.

Meanwhile, just downstream, this summer Pierce County completed an effort to reconnect about 150 acres of floodplain and carve a new side channel to the river. During last week’s high flow, this new channel took about 30% of the flow out of the mainstem Puyallup, dramatically reducing pressure on riverbank levees that protect a large subdivision.

The project in Orting is one of the first Floodplains by Design projects to be completed, and the first to stand the test of a big flood. What’s more, in addition to the dramatically reduced flood risks in this area, these projects are also providing other important community benefits. The side channels and reconnected floodplains provide critical salmon spawning and refuge habitat. And when the waters recede, city and county residents are left with about 2 miles of scenic riverfront open space.

The City of Orting and Pierce County deserve kudos for working together on a large stretch of river to implement projects that combined, reduce flood risk, restore critical habitat for salmon and improve the quality of life for residents of the area. This is exactly what Floodplains by Design program is all about – working together to implement big projects that produce big results.

Related Blog Posts

Fisher Slough & the Flood

The Skagit River crested at 31.5 feet on the river gauge in Mount Vernon on Saturday morning. This is the highest river we’ve seen since the Fisher Slough project was completed and the highest the Skagit River has been since 2006. That said, it’s nothing compared with the biggest floods seen on the Skagit in 1990, 1995, 1906, 1951 (all ~37 feet).

This is the first time the flood overflow structure has been been needed and its working beautifully! The flood storage area was approaching capacity and rather than overtopping our new levees, potentially damaging these levees, and sending the water to places we don’t’ want it to go, the water went over the emergency spillway made of rock built for these types of events.

This was inspirational. The structure was working beautifully, the levees were containing the flood waters and the there was no standing water on the adjacent farmland. The entire project was operating as expected. It was something to behold and evidence of the exceptional work of the project team and our partners!

This wouldn’t have been possible if not for the collaboration and trust from the local farming community, Dike Districts and partners such as WWAA and their inclusive, transparent knowledge into the design process!

Learn more about Floodplains by Design.