Our Director of Strategic Partnerships, Bob Carey, shares a moment of solitude and deep appreciation for salmon on the upper Skagit River.

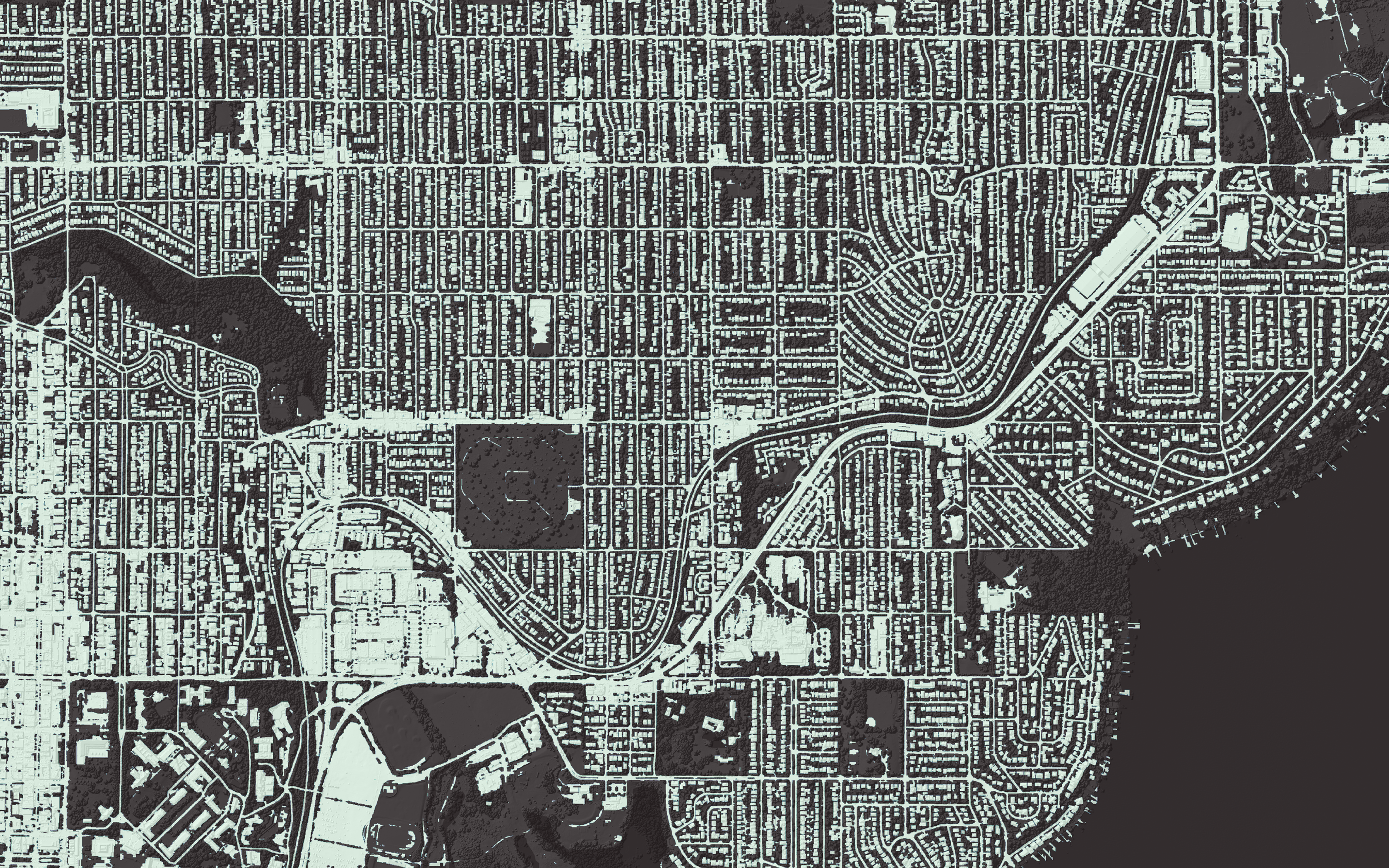

Water 100 – Engaging the Business Community to Regenerate Puget Sound

The Water 100 Project. is an initiative of The Nature Conservancy and Puget Sound Partnership. This initiative includes scientists, engineers and policymakers working together to identify the 100 most substantive solutions for a clean and resilient Puget Sound. Together, we are looking to integrate the resources and speed of the private sector to take meaningful action toward a water resilient future.

Water 100 Project Inspires Solutions for Puget Sound

A new initiative is driving to align this incredible pool of talent and ingenuity to tackle one of the most pressing challenges facing our region – how to address the threats of pollution, development and climate change to the body of water that defines this region, Puget Sound itself.

“None of us can solve the challenges of Puget Sound on our own,” says Jessie Israel, our Puget Sound Conservation Director. Through the Water 100 Project, an initiative of The Nature Conservancy and the Puget Sound Partnership, we’re creating a movement that brings together the Puget Sound business, government, NGO and scientific communities to identify, assess, fund, and implement the 100 most substantive solutions for improving our region’s water.

Kathy Woodward - Projects and Innovation Manager

Forests and Swift Water: A Love Story

We filled in the last puzzle piece at Foulweather Bluff

This latest acquisition protects the Preserve’s second-most important physical feature, after its namesake 50-foot feeder bluff, a brackish marsh which is fed by a freshwater drainage from the northeast. This site has been identified by the Washington Natural Heritage Program as one of the top 20 most significant coastal wetlands in the Puget Sound region. The driftwood berm separating the marsh from Hood Canal is breached periodically by winter storms and high tides, introducing a more saline element into the marsh.

Innovations in Flood Risk Management - a Conversation with Pew Charitable Trusts and More

Washington state’s innovative Floodplains by Design program is leading the way toward holistic river and floodplain management, bringing together all the benefits of investing in river restoration: communities protected from flooding, thriving farms, habitat for salmon and other wildlife, clean water, and recreational opportunities.

Protect Nature: Vote No on I-976

NOAA grants $1.5 million for salmon habitat restoration

Puget Sound Science - A Human-Centered Approach

We are all the end users of science for the Puget Sound. No amount of money or science alone is going to protect and restore the Puget Sound. But, people changing their behavior will. Design the right tools that connect people to what they care about in to the Puget Sound each day and people will change. Design thinking starts with learning what they care about.

The Only Constant is Change: Explore How Rivers Meander Over Time

Boeing Gives Big to Support Our Work to Clean Up Puget Sound

Two-Minute Takeaway: What is an Atmospheric River?

November 'Photo' of the Month: Water's Effect on the Landscape

Two-Minute Takeaway: What is Riprap?

Local Scientists Work on Water Supplies Around the World

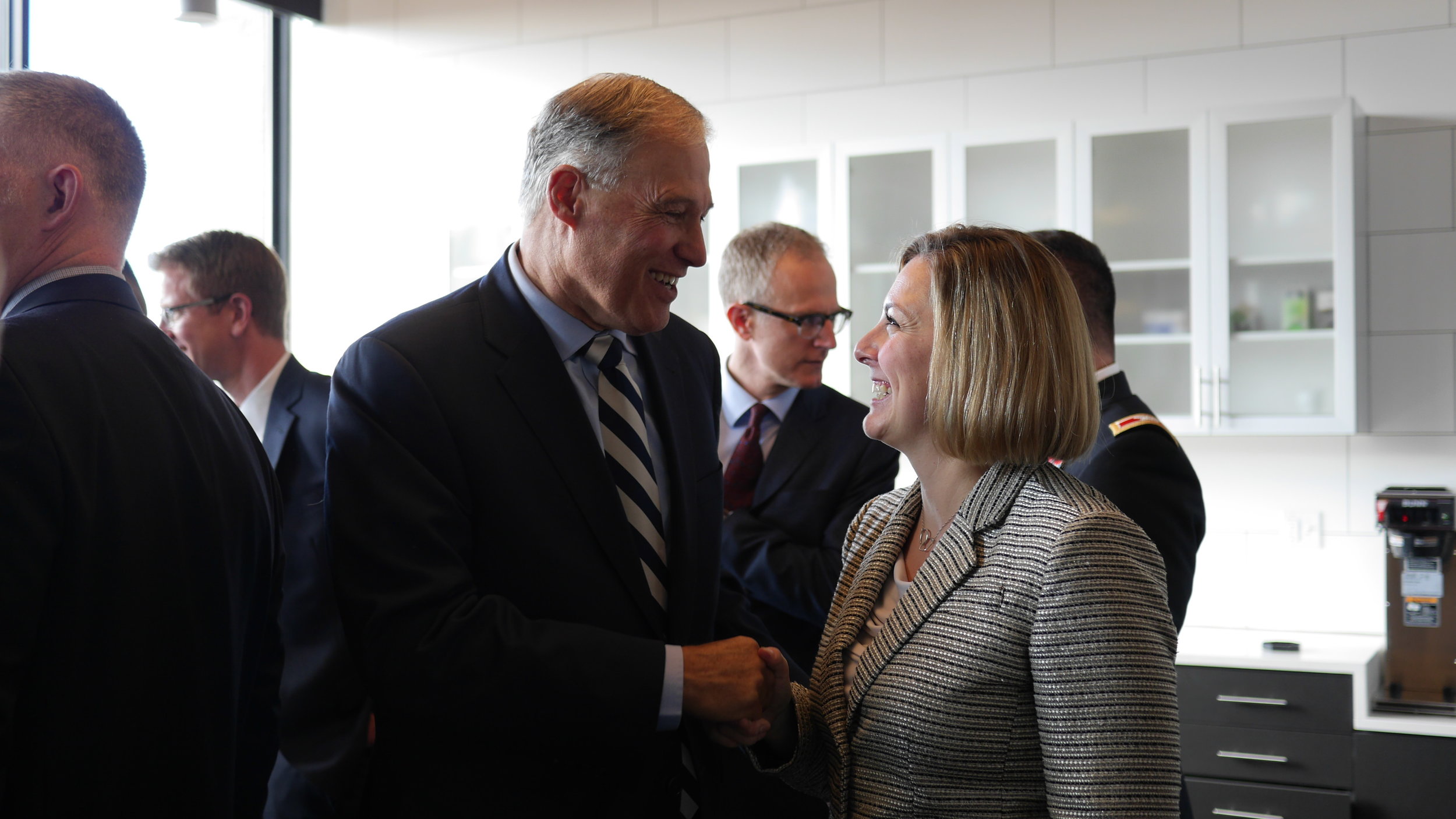

Making history in Puget Sound and in our kitchen!

“High five to Christy from CEQ! This is better than a fourth quarter Seahawks drive!” -Chairman Mel Sheldon, Tulalip Tribes

“Save the salmon and we save the Orca... In saving the Orca, we save ourselves.” -U.S. Congressman, Denny Heck

By Jessie Israel, Director, Puget Sound Conservation

Photo by Zoe Van Duivenbode

Puget Sound is a national treasure. We have orcas off our downtown shorelines, tribal histories that date back thousands of years, salmon running in our urban streams, right in the midst of one of the fastest growing regions in the country.

We were proud to host a news conference with our local, state, federal, and tribal partners about White House efforts to take the next step in saving this national treasure. As he stood in our conference room, looking out at the Sound in all its beauty, Governor Inslee said, “Today’s announcements mark an important step on the path to restoring the health of Puget Sound, the recovery of our salmon species and fulfilling our nation’s commitment to Washington’s tribes.”

As one of America’s largest estuaries, Puget Sound is of national and tribal treaty significance. Recovery efforts are starting to yield results, but damage still outpaces recovery.

President Obama and Congress acknowledge that recovery in Puget Sound is still possible, and provide funding commensurate with that awarded to other estuary programs, such as Chesapeake Bay or the Great Lakes.

We are gratified to see this announcement, which elevates Puget Sound recovery as a national priority and will improve alignment among federal, tribal, state, local and non-governmental actions for salmon, for Puget Sound, and for Tribal treaty rights.

White House News Release: Taking Action to Protect the Puget Sound Watershed

Governor Inslee News Release: White House, Washington state and federal leaders announce new initiatives for Puget Sound recovery

KING: Puget Sound recovery effort gets a 'historic' $600M boost

Seattle Times/AP: Obama Administration steps up efforts to protect Puget Sound

KUOW: Puget Sound In Line for Environmental Health Boost

Northwest Public Radio: New Federal Action Plan for Puget Sound Restoration

Seattle PI: Obama Administration steps up to the plate on cleaning up Puget Sound

KOMO: Feds step up efforts to protect Puget Sound marine life

KNKX: New Federal action plan for Puget Sound restoration leverages tribal treaty rights

CEQ: Taking action to protect the Puget Sound watershed

Honored guests joined TNC team at our Washington Field Office for today’s news conference:

• Jay Inslee, Washington State Governor

• Mel Sheldon, Tulalip Tribes Chairman

• Leonard Forsman, Suquamish Tribe Chairman

• Denny Heck, U.S. Congressman

• Derek Kilmer, U.S. Congressman

• Christy Goldfuss, White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) Director

• Col. John G. Buck, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

• Dennis McLerran, Regional Administrator EPA

• Barry Thom, Regional Administrator NOAA

• Martha Kongsgaard, Chair, Puget Sound Leadership Council

Our approach to recovery here is unique: we have aligned the Tribes, federal agencies, state and local governments, and multiple NGOs to agree on approaches to recovery. Increased federal action and support will accelerate this good work.

Key take home points from today’s event:

- The federal government is taking new action to protect and restore the Puget Sound watershed, through the establishment of a Federal Puget Sound Task Force and a new Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) directing federal agency restoration activities in the region.

- White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) and federal agencies are announcing new federal funding commitments to improve estuary health and contribute to salmon recovery:

- A $248 million investment from EPA, the State of Washington and Puget Sound tribal governments, over the next five years, which will go toward improving estuary health. EPA is contributing $124 million through the National Estuary Program, matched with an additional $124 million from the State.

- Two completed habitat studies by the Army Corps and partners with recommended funding. The first, the Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project, recommends approximately $450 million in large-scale estuary and coastal habitat restoration. The second, the Skokomish River Basin Restoration Project, recommends a $20 million project to open over 40 miles of habitat along the Skokomish River.

- An additional $100 million commitment by the Army Corps of Engineers to improve fish passage at Mud Mountain Dam, located on the White River, with an initial $30 million included in the President’s FY2017 budget to begin construction.

A Critical Ingredient to Washington's Hops

Written by Kara Karboski, Kristen Taggart & Ryan Anderson, Washington RC&D Council

Photographed by Heather Hadsel

Washington State is a land shaped by fire and water. Mighty rivers have formed our landscapes and help to support wildlife, power our homes and cities, and water our farms. Likewise, fire has existed in the forests, prairies, and shrub-steppe of our state for thousands of years as an important agent of change and rejuvenation.

Toward the Yakima Valley, the Naches and Yakima Rivers flow out of the Cascade Mountain’s forested slopes in central Washington State and into the Columbia River. The Yakima River is one of the most productive watersheds of the Columbia. Unique folds in Columbia basin basalt (LAVA!) combined with gravel and sediment created vast floodplains that once were, and soon will be again, critical habitat for upwards of a million adult salmon returning to the Yakima Valley throughout each year.

CelebrateForests and Beer with OktoberForest

The water that runs from the snow and forests of the Cascades has become a vital economic driver in modern times. The valley’s sun, soil, and irrigation supply, along with its hard working community, have created a hop industry that supplies approximately 70% of the nation’s hops. That means 70% of our beer is dependent on reliable, clean water that originates in the forests of the eastern Cascades.

September and early October bring familiar and odorous reminders that Yakima is “Hop Town, USA.” Crews cut hop vines off of trellises and haul them to various processing facilities while the familiar smell of beer’s most distinct flavoring agent – hops – drifts through town. Occasional whiffs of smoke from prescribed fires blow through town as well. These autumnal smells are both important to the beer industry and to the forest. Beer needs clean water that has been filtered and stored in healthy forests. The dry forests of the eastern Cascades need occasional low-severity fires to protect them from devastating fires and to preserve their necessary function of providing clean water.

But our forests are unhealthy. Natural fires, started by lightning during the dry months, used to dance their way across the eastern forests of Washington. These low- to moderate-severity fires are necessary for the health of the forests and served to burn through the vegetation on the forest floor returning nutrients to the soil, naturally thinning the forests, opening up the understory for new plant growth, and creating important habitat for wildlife. Periodic fires like these reduced the available build up of fuels for the next fire, continuing the cycle of low- to moderate-severity fires.

We have been very effective at fighting fires to protect forest resources and communities. This has resulted in the suppression of natural fire which would otherwise reduce the buildup of dead vegetation. With higher fuel loads, fires burn hotter and faster. And these fires are much more difficult and costly to fight. These megafires are consuming resources – economic, environmental and human – at an unacceptable rate.

Megafires can affect water supplies in devastating ways. Without vegetation to slow down the movement of water, it can move large volumes of soil, ash, and other sediment. Although sediment movement, landslides, and debris flows are all normal processes in the Cascade Mountains, they can occur at super-natural scales if our forests suffer burns that are also super-natural. During Washington’s Carlton Complex Fire, for example, massive debris flows destroyed infrastructure such as irrigation systems, roadways, and buildings. When debris flows like this occur above reservoirs or water intake structures, capacity of those systems can be lost for long periods of time or indefinitely. This is on top of the water quality lost due to more silt running into waterways. These events change the clarity of water, its taste and odor, and can result in other adverse effects on water.

If our forests are not treated, through mechanical thinning or planned and coordinated burns called prescribed fire, a highly destructive fire could cause a disruption of our clean, reliable water, impacting our hop production, drinking water, and brewing industries and create major expenses for water users.

Healthy forests and the reliable water they produce are not just for beer, but for the benefit of all downstream communities. Some communities are recognizing the risk from uncharacteristically large and destructive fires and the potential impacts these fires would have on their clean water supply. In New Mexico, a community in the Santa Fe Watershed recognizes the value of healthy forests for providing clean water. This type of investment is also seen in the Rio Grande Water Fund. Communities are recognizing the risks and are protecting their watersheds with investments from utilities and other funders that depend on healthy forests.

In our state, the Washington State Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network is working to connect communities that live in fire prone areas so that they can learn from one another, share resources, and support each other when fires affect them. Understanding the impacts of fires on our water resources is one piece of this complex issue, and communities are coming up with local solutions that work best for them.

The Yakima Valley is blessed with hops and beer, forests and fish. Both fire and water play an important role in supporting these natural resources. We can protect these resources and our communities by recognizing the role fire plays, both good and bad, and by addressing these risks for the benefit of all.

Read about our work in Yakima Valley

Learn more at OKtoberForest.org

Stilled by the Streams: September Photo of the Month

Written & Photographed by Katherine Scheulen, Northwest Photographer

This particular photo is meant to evoke calmness, the almost meditative state you feel when gazing at any creek, river or stream. The dusky light, the smoky water, the stillness of an evening where only rushing water roars in your ears.

I really wanted some bluish, low, dusky lighting, so my girlfriend and I waited until evening to wander out to the Old Robe Canyon trail along the Mountain Loop Highway. I wanted to pick somewhere with a good steady flow of water and a trail that wouldn’t be too strenuous to hike back in the dark. Robe is a well-built trail that fit the bill. I set up my Nikon D3300 on a tripod looking out toward the Stillaguamish River, framing it with a few close rocks and a point of rock jutting out into the water. Set the aperture to f/16 with a long exposure since I really wanted the water to look glassy and almost smoky, a good contrast to the jagged roughness of the rock. I had my girlfriend actually press the shutter for me as I scrambled out onto the point. Having one person in the shot to show the scale of the landscape is a great tool I enjoy using. The only trouble was getting me to hold still long enough for the shot!

Landscape photography attracts me in many ways, but especially as a device telling a story about wild places. I grew up in western Washington, the daughter of a mountaineer and an avid recycler backing the 80’s when recycling wasn’t just a given. Conservation and leave no trace ethics are practically in my blood. I cherish and respect our public lands. My hope is always that my photography reflects those feelings, whether it be an intimate look at an individual leaf in its perfectly niche design or a huge panorama to shrink ego and lift the spirit.

Seattle is her home, and she is a native Washingtonian. Katherine has been hiking since a very young age with her father, who was an avid mountaineer in the 80’s and 90’s. Recently, she has started to do a bit of backpacking too and can’t wait for her next adventures. Follow her adventures on instagram: @hiker_katherine

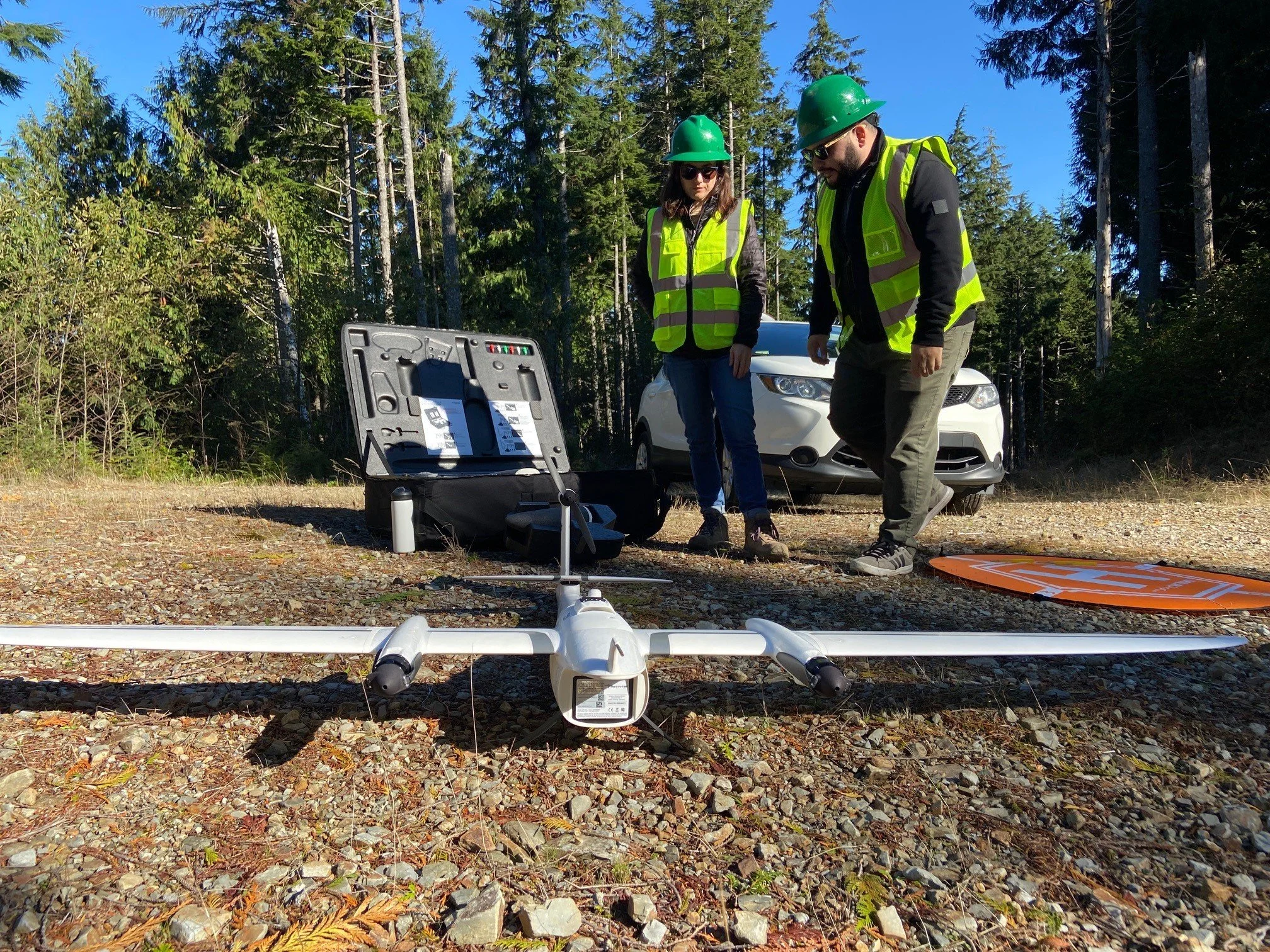

Jared Rivera: A Doris Duke Conservation Scholar

Written & Photographed by Kat Morgan, Puget Sound Community Partnerships Manager

On a chilly morning in the North Sound, 20 semi-sleep deprived undergraduates from across the country (there were some fireworks and late nights at their campsite the previous night) stood in our Mount Vernon office parking lot learning about who The Nature Conservancy is, and our work in Washington, particularly Puget Sound. These were the 2016 cohort of Doris Duke Conservation Scholars, a program sponsored by the University of Washington. This two year program is designed to help foster and ultimately increase diversity in the conservation workforce. These were the first-year students – freshmen and sophomores - participating in this 8-week field program in Washington. They visited conservation projects and professionals around Puget Sound, learned about current conservation needs and issues, and about the people doing this work. We toured our Mount Vernon office to give them a sense of what it might be like to work for The Nature Conservancy, and then headed to one of our flagship project sites – Port Susan Bay. Most students knew the Conservancy purchased and conserved lands. Only one knew that we actively managed those lands, or that we supported and implemented large-scale, landscape changing projects beyond our own ownership.

After hearing about the needs for restoring floodplain systems across Puget Sound, they had lots of questions about how you work with communities to do this work. What kinds of outreach were required, and how did you go about it? We talked about how each community has different needs, and you approach each community differently depending on the circumstances and people involved. They nodded their heads when we talked about the similarities – in each community, you ask questions and listen. You listen a lot - to understand what is needed, what is important to the people who live in that place, and you work together to find space for all those needs in a project.

We toured the Port Susan Bay restoration project site at low tide, when all the restored tidal channels and estuarine marsh were visible and visited the flood return structure, installed to address local flood issues as part of the project. Migrating shorebirds moved around the shallow pools left by the tide. The students marveled at the remoteness of the site, even though houses are visible all around, and the subtle energy, where at a distance everything appears very still, but when you get closer, you see song and shore birds flitting round the marsh, rushes moving in the breeze, and raptors on the wing looking for lunch.

As we wrapped up the tour, we turned the tables and I asked questions of this group of future conservation professionals. Jared Rivera is one of the Doris Duke scholars. He studies environmental engineering at UCLA. As a Native American, Jared is very interested in the intersection of social justice and conservation, in making sure Native American communities are engaged in problem-solving and decision-making around natural resources. Jared appreciates the interdisciplinary teams the Conservancy puts together to tackle conservation problems, and one day, when he finishes his environmental engineering degree, is interested in a seat at the table.

PROFILE

Name: Jared Rivera

Hometown: Murrieta, Southern California. Going to college at UCLA.

Murrieta is located in the center of the Los Angeles San Diego mega region of 20 Million people. After interstate 15 was built in the 1980’s, suburban developments started being constructed. Today, Murrieta is known as a commuter town and the largest employer is the school. I know this area though. I have family on Camano Island. It’s really interesting to hear about your projects here.

Childhood Dream/what did you want to be when you grow up?:

Until I was 17, I wanted to join the Marines. Then my ideas changed. I had an AP bio teacher who taught us about ecology and took us on field trips to the Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies. I was fascinated by a project they were working on of sustainable algae fields for biomass production. I applied for a student study program at the Wrigley Institute and was accepted.

What about our work do you find most inspiring? What is most surprising?

The Levees at the Port Susan Project. The fact your conservation organization isn’t afraid to make changes to the environment, and to build infrastructure if it will help you accomplish your goals. Humans have already meddled with nature to mess it up. The only way to fix it is to keep meddling.

What would you most like to see The Nature Conservancy work on that you didn’t hear about today?

I would like to see The Nature Conservancy become more involved in social justice issues. Particularly as a Native American, I would like to see more indigenous communities included in the problem-solving and decisions around our natural resources.

What would make you want to work for us?

I am really excited about the interdisciplinary approach you described bringing experts from all different fields together to problem-solve, to have a seat at the table, particularly involving social justice issues.