Freight driver by day, dairy farmer by… day. Meet Paul along with his 20 Jersey cows and learn about the 100 year legacy of the Fantello farm.

Ben and His LegenDairy Maple View Farm

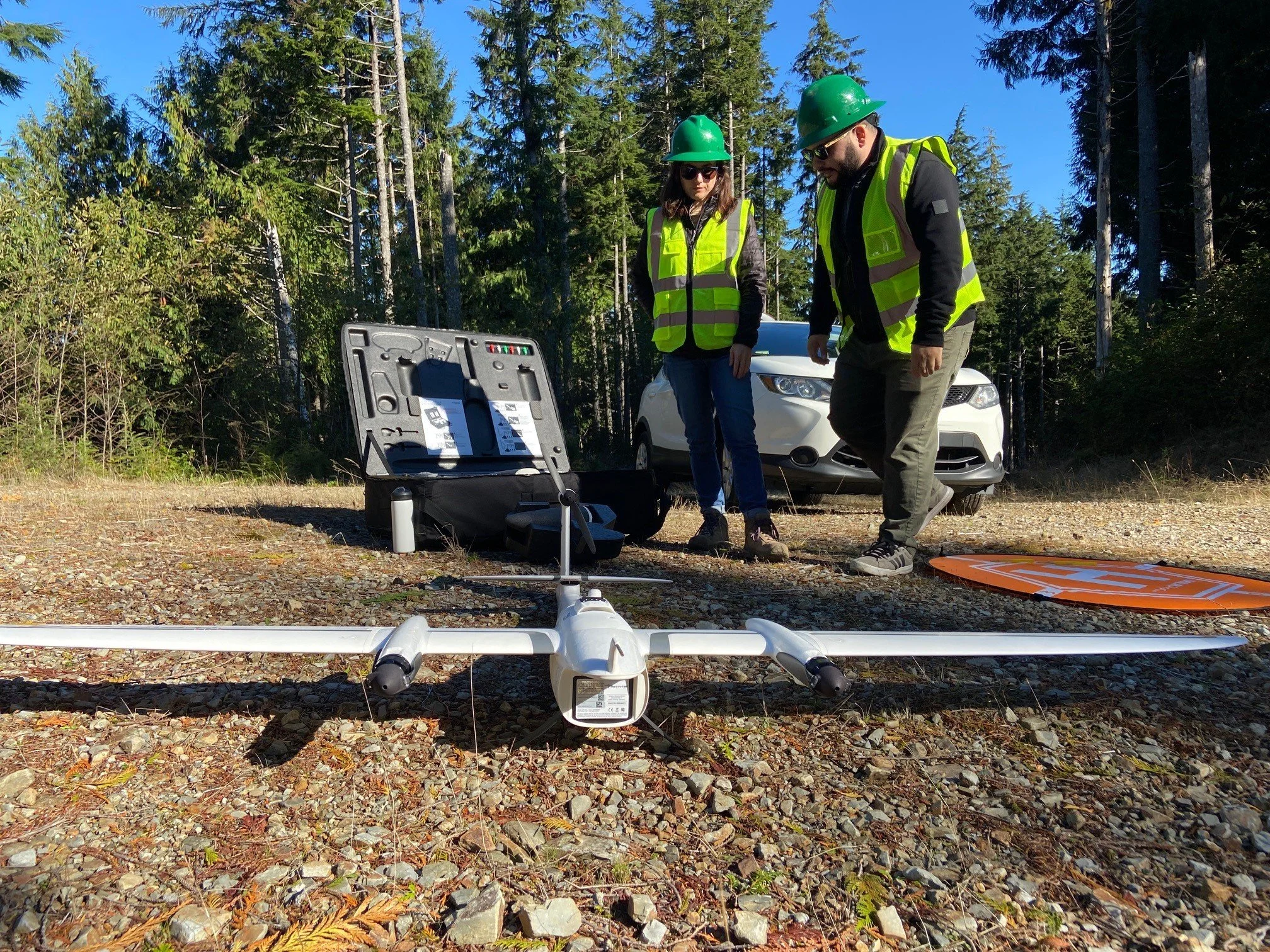

A New Tool for Farmers in a Changing Climate

Farms as Whole Ecosystems

From Photos to Community Empowerment — Follow These Farmers' Journeys

A Tasty Tour of Sustainability at Seattle Culinary Academy

Farming, from Field to Pint Glass

Sink your teeth into trivia on Washington’s favorite fruit

If the old adage is true—that an apple a day keeps a doctor away—then the world owes a lot to Washington.

The Evergreen State produces more than half of all apples grown in the United States for fresh eating, according to the Washington Apple Commission. In fact, Washington apples are sold in all 50 states and more than 50 countries, meaning that many a person enjoy the fruits of Washington’s labors.

For Washington residents, our expansive apple orchards are one reason it’s easy to buy and enjoy local fruit.

Each and every Washington apple is picked by hand, and there are more varieties than a person can remember. The industry here is based primarily on seven principal varieties: Red Delicious, Gala, Fuji, Golden Delicious, Cripps Pink and Honeycrisp.

But an enterprising eater can sink their teeth into many more varieties, including rare heirlooms. Or search farther afield for your favorite of more than 7,500 varieties grown worldwide.

The sweet, crunchy apple is a large part of the economy and culture in Eastern Washington, home of Nature Conservancy Leadership Council and former board member Jack Toevs. For Jack, growing apples is a family operation, now involving his son. “The family has been involved in farming for centuries,” he said. “It’s our heritage.”

He’s observed many changes over the years. For example, the Red Delicious has been overtaken in popularity by the Gala. And many growers – himself included – have gone organic, meeting the public’s demand for more healthy and sustainable fruit. Our state cultivates 14,000 acres of certified organic orchards, according to the Washington Apple Commission.

It seems Washington has an ideal climate for apple production – particularly organic apples. “It’s a dry climate, with fewer problems for disease and insects. It’s just been a great place to grow apples,” said Jack.

In addition to serving as a Conservancy board member, Jack and his wife volunteer as stewards at the Conservancy’s Beezley Hills Preserve, which sits atop the hills visible from their orchard in the town of Quincy. This Eastern Washington preserve is awash with wildflowers every spring.

In Eastern Washington apple country you’ll find a strong connection between people and nature. That’s one of the reasons why The Nature Conservancy has a presence here, as well as in the Yakima Valley to the south and Skagit farmlands to the west. It’s the kind of win-win connection the Conservancy strives to create in communities everywhere we work: conservation that will bear fruit for generations.

Photovoice Project Shines a Light on Farmers' Challenges, Hopes

Video: How a Skagit Valley Farm is Adapting Amid Climate Change

Gratitude for Harvest

By Mike Stevens, Washington State Director for The Nature Conservancy

Harvest season brings the bounty of earth and sea to our tables.

In the Pacific Northwest, we enjoy plentiful seafood, fruits and vegetables, grains and meats, even wine and beer that come from within a day’s drive.

Yet ancient Romans built roads to transport salt, grain and olive oil to the capital. Today we’d be hard-pressed to do without our coffee, tea, or chocolate here in the Northwest.

How can we work both locally and globally to ensure that natural systems that sustain our food supply—clean fresh water, a healthy living ocean, productive soil—will support the coming population of 9 billion? And how do we protect and restore wild places in the face of global demands for land and water?

In Washington, the Conservancy is collaborating with farmers around Puget Sound to preserve working farms and expand practices that produce clean water and healthy soils. We’re partnering with commercial fishermen and tribes on the coast to sustain fishing. We’re supporting statewide solutions to floods and droughts that threaten water for drinking, farms and fish.

Globally, the Conservancy is working with food growers, from large companies to local farmers, to keep soils healthy and water quality high. In Brazil we’re working with agricultural giant Cargill and with local farmers on practices to combat deforestation and protect the Amazon. In Kenya, we’re working with families who raise livestock to improve market access while protecting their lands and wildlife. Learn more at https://global.nature.org/content/the-next-agriculture-revolution-is-under-our-feet

The work we do to protect nature and our food supply is not possible without your support. In this season of gratitude, I am most thankful for your generous gifts.

Learn more about our work

A Piece of History Gone But Not Forgotten

Written and filmed by Joelene Boyd, Puget Sound Stewardship Coordinator

Recently, a piece of history was removed from the landscape at Port Susan Bay Preserve. The house that had been a part of the landscape for over 60 years is now gone. Homesteader, Menno H. Groeneveld bought the house for a bargain price as the Interstate freeway was expanding through Seattle and moved it to the property so the story goes.

Groeneveld was an ambitious man who inherited a portion of the tidelands of Port Susan Bay back in the 1950’s. Initially he thought his inheritance was agriculture land until, upon his arrival from the mid-west, he realized it was not. However, he didn’t let that dampen his dreams and set to work building a dike around 160 acres so that he could pursue his calling - farming.

Every time I think of all of the options that someone in his shoes could have done I’m struck by the pure determination he must have had to embark on building a dike around then mud and estuary and start a farming operation.

In 2012, The Nature Conservancy removed this outer dike and restored 150 acres to estuary habitat to support juvenile Chinook Salmon, water birds and other estuary dependent fish and wildlife species.

As I watched the house come down I knew it was the right thing for conservation and giving this piece of land back to the natural world. But I was also sad that this piece of history was being erased from the landscape.

What's next for this area? In the immediate future I will plant some annual grass to keep the weeds at bay but longer term it would be great to restore native trees and shrubs and install a kiosk of sorts for people to come, congregate and learn about Port Susan Bay and The Nature Conservancy's amazing work in restoring and protecting this special place.

The house is now gone but the story of this man and his resolve will stay with me for a long time to come.

Learn more our Port Susan Bay

Farming for Wildlife

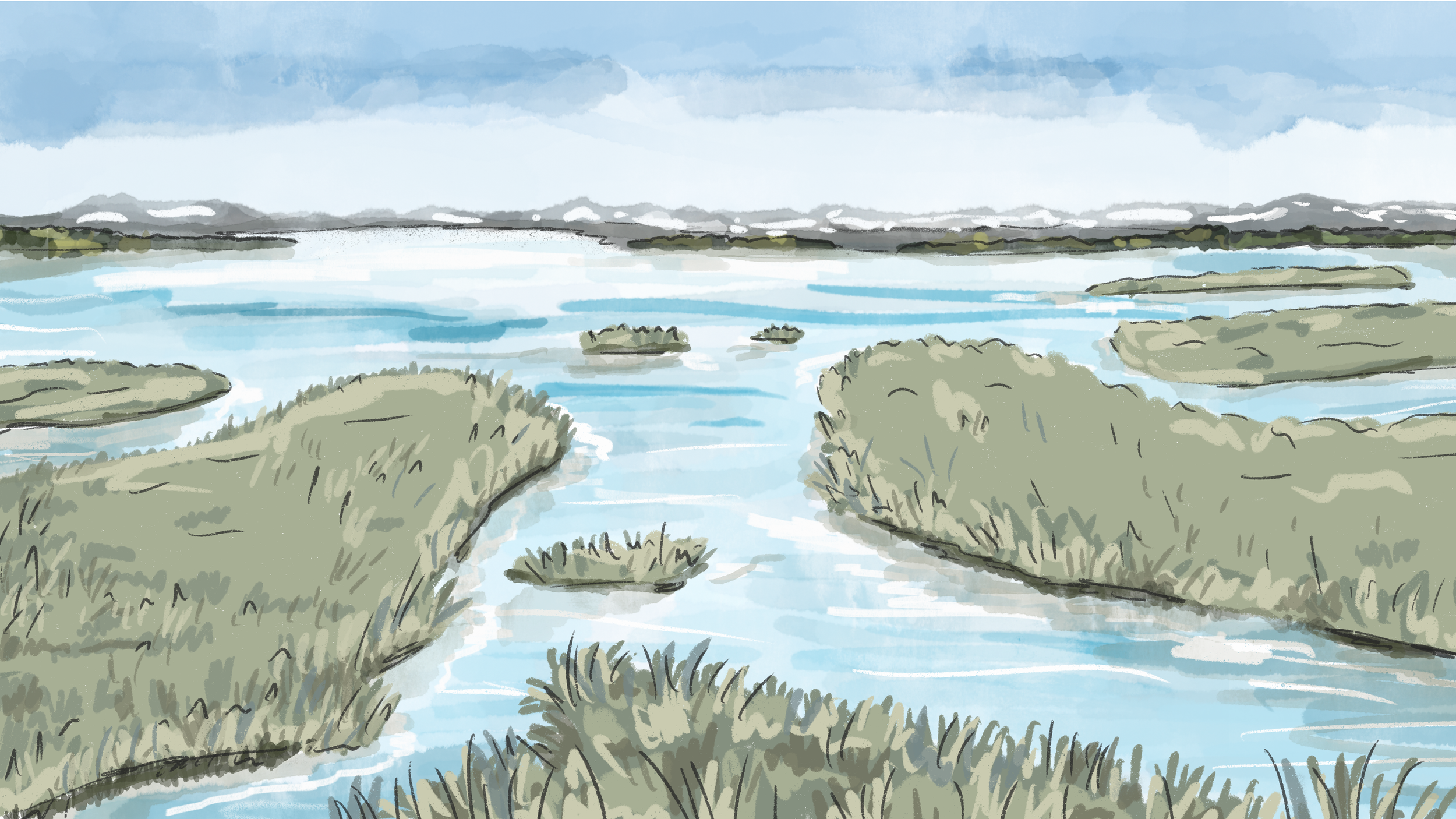

Farmers in Washington’s Skagit River Delta in northwest Washington State are adding a new crop to their fields — shorebirds.

By flooding parts of their fields with 2 or 3 inches of water for part of the year, these farmers are creating new or improved habitat for shorebirds such as Western sandpipers, black-bellied plovers, dunlins and marbled godwits and at the same time improving the health of the fields for farming.

The dedicated farmers are participating in an innovative research project The Nature Conservancy has launched in cooperation with Washington State University, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Skagitonians to Preserve Farmland, and the Western Washington Agricultural Association.

Called “Farming for Wildlife,” the project is about finding ways to help provide some of the shorebird habitat that’s been lost while also supporting local farms. The partners involved are studying the relationship between three farming practices (mowing, grazing, and flooding) and habitat for migratory shorebirds. The intent of the experiment is to discover how habitat rotation can be compatible with crop rotations in the Skagit Valley.

THE SKAGIT DELTA COMMUNITY

The Skagit Delta is a vibrant rural community—one of the last strongholds of farming in Western Washington and a bread basket both regionally and nationally. The local community is rightfully proud and protective of its family farming heritage which reaches back for generations.

At the same time, the delta is rich in wildlife. Though altered over the years by human development, diking and draining, the delta continues to support tidal marshes and riverine habitats which host one of the largest and most diverse concentrations of wintering raptors on the continent.

And in recent winters, biologists surveying the delta have counted more than 150,000 dabbling ducks and more than 65,000 shorebirds, underscoring its status as a critical stop along the Pacific Flyway.

A WIN FOR FARMERS AND FLIERS

Worldwide, shorebirds have suffered dramatic population declines, and one of the greatest threats to these populations is the loss of wetland habitats. In the Skagit Delta, we’ve lost 70 percent of estuarine and 90 percent of freshwater wetlands. Despite that loss, the Skagit Delta still supports 70 percent of Puget Sound shorebirds during migration. Kevin Morse, the Conservancy’s Puget Sound program manager describes the delta as “one of the last best places for shorebirds.”

“They’ve lost this type of habitat along their migratory routes,” Morse said.

The real payoff will come if the Conservancy learns which practices are successful and can be replicated in other areas of the country. As part of the study, the Conservancy has rigorously monitored use of the habitat by shorebirds at different tide heights, as well as the presence of weeds, invertebrates in the soil and overall soil condition. If significantly higher numbers of shorebirds are feeding in the pilot fields than in neighboring farm fields, and the soil condition is measurably improved, and farmers embrace the treatments, that will spell success.

“If 100 years from now,” farmer Dave Hedlin said, “there are healthy viable family farms in this valley and waterfowl and wildlife and salmon in the river, then everyone wins.”

A Ride Through Puget Sound

Last night, I needed to get into a better head space, and I knew that being outside would do it. I grabbed my bike and headed straight from my neighborhood on the hill to the flatlands below. The houses thinned out and soon I was in open farmland.

One of my favorite ride starts out along the Skagit River. I don’t see the river because there’s a dike between the road I’m on and the river, but the mark of the river is evident. The road winds and twists – something not many roads in the flat lands do because they’re on a big grid system – and I discover new sights and sensations around each corner. A house with an orchard, the alpaca farm, wide open fields. The very ground that I’m looking out over is a product of the river. This silty, rich soil is some of the best in the world for farming.

Some places I pass through are shady because of the towering cottonwoods that grow next to the river. An eddy in the wind patterns brings the river’s cool air to greet me as I heat up from the exertion of my pedaling. Soon I’m in Conway and pass over the green waters of the south fork Skagit. My first “hill” is the bridge that carries me over the river.

I continue across Fir Island where the farmland stretches out toward salty Skagit Bay. I stop in when I see a friend out in his yard. He and his crew have butchered a hog today and planted 10,000 young plants he will grow for winter vegetables. He notes that my steel-framed bike is a good thing on these Skagit County chip-seal roads, and a bike-savvy farm hand nods in agreement. The sun is fading and we all want to head in for dinner. I hit the road again, now passing over the north fork Skagit River (hill #2!) and onto rocky, wooded Pleasant Ridge. The quiet forested roads here offer up choruses of bird song.

Soon I’m on the flat lands again – I take the long, straight roads now and my shadow stretches out in front of me. I am racing the sun for home. My mind is clear and I remember why it is that I live and work here. This place is a patchwork of bountiful farms, open space, towering trees, cool river air, friends and community.

I am home.

Jenny Baker is a Restoration Manager with TNC. She is grateful to be involved in work that impacts places around Puget Sound like the Skagit delta.

Conservation Can Be Delicious

Meet Kevin Morse

Our Puget Sound Working Lands Program Director!