Floodplains by Design—a collaborative and community driven approach for reimagining floodplains—is being used as a model for flood prevention and management across the U.S. and internationally, creating floodplains that work for people and nature

Floodplains Beyond Borders

Building Climate Resilience: The Urgency of Updating the Growth Management Act

Innovations in Flood Risk Management - a Conversation with Pew Charitable Trusts and More

Washington state’s innovative Floodplains by Design program is leading the way toward holistic river and floodplain management, bringing together all the benefits of investing in river restoration: communities protected from flooding, thriving farms, habitat for salmon and other wildlife, clean water, and recreational opportunities.

The Only Constant is Change: Explore How Rivers Meander Over Time

Creative Ideas to Put an End to Flooding Risk

Two-Minute Takeaway: What is an Atmospheric River?

Two-Minute Takeaway: What is a Floodplain?

Do you have launching toe? Probably not, unless you’re a levee!

Model Restoration Project is Working for Salmon and for Farmers

The Two-Minute Takeaway: What is a Floodplain?

Honoring Our Floodplain Champions

Natural resource leaders honored at first Floodplains by Design celebration

Written by Bob Carey, Strategic Partnership Director

Agencies and tribes recognized for their leadership in improving river management to improve flood protection, restore salmon habitats, improve water quality, and enhance outdoor recreation. More than 150 people came together to celebrate the Floodplains by Design Partnership and honor seven floodplain champions and project partnerships at a dinner Monday, September 12, in Seattle.

The Floodplains by Design Partnership, led by the Washington Department of Ecology, The Nature Conservancy, and the Puget Sound Partnership, identify and support large-scale projects that are built from the ground up by local governments, tribes and community stakeholders. Collectively the partnership is pursuing a vision of collaborative, integrated management delivering results to help Washington’s communities and ecosystems thrive.

In four short years, with the support of $80M in new state funding, the Floodplains by Design partnership has reduced flood risks to hundreds of families in 25 communities while restoring habitat along 10 miles of salmon-producing rivers, protecting 500 acres of farmland and creating new river access and trails.

“Floodplains by Design is not just a grant program, it’s a movement!” Bob Carey from The Nature Conservancy told the celebrants. “It’s a movement to put our shoulders together to make our communities safer from flooding, to make our salmon runs stronger, and to ensure future generations have local food, clean water, and recreational opportunities.”

Three locally-driven river management partnerships were recognized as 2016 Floodplain Luminaries, for their steadfast pursuit of an integrated, resilient river management program and delivering results in support of a prosperous community and healthy environment:

· The Yakima River Floodplain Project

· The Dungeness River Floodplain Partnership

· Puyallup Floodplains for the Future Partnership

Four organizations were honored as 2016 Floodplain Champions for their steadfast support of integrated, resilient river management programs that deliver results for a prosperous community and healthy environment, include:

· Washington State Department of Ecology

· US Environmental Protection Agency

· Tulalip Tribes

· Puget Sound Conservation Districts

Award presenters included Washington Sen. Karen Keiser, D-Kent, Rep. Richard DeBolt, R-Chehalis, Rep. Steve Tharinger, D-Dungeness, King County Executive Dow Constantine, NOAA Fisheries Regional Administrator Will Stelle, Puget Sound Partnership Executive Director Sheida Sahandy, and Washington Department of Ecology Program Manager Gordon White.

Presenting sponsors for the Floodplains by Design conference were Anchor QEA, ESA, HDR Inc. and Northwest Hydraulic Consultants. Dinner sponsors were Watershed Science & Engineering, Northwest Regional Floodplain Management Association and WEST Consultants. Funding for the Conservancy’s engagement in Floodplains by Design has been provided in part by the Boeing Company and The Russell Family Foundation.

Learn more about Floodplains by Design

A River Revolution: From 0 to 56 in four years

Written by Bob Carey, Strategic Partnerships Director

Maps by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

Floodplains by Design, a public-private partnership aimed at revolutionizing river management across Washington, came together in 2012 with the goal of making our communities safer and rivers healthier. It started as a concept: get the leaders of programs and interest groups that influence coastal and riverine floodplains out of their silos, have them work together to figure out how to manage these landscape in a collaborative, integrated fashion, and we’ll collectively do a better job of delivering society’s goals of reduced flooding, stronger salmon runs, clean water, economic development and a high quality of life.

Floodplain managers of various sorts – county flood managers, tribal fisheries biologists, agricultural drainage districts, conservationists, etc. – embraced the concept, having seen the folly of trying to “control rivers” and the inefficiency of trying to manage only one cog in a complex social and environmental landscape. In 4 short years the concept has evolved into a broad partnership – a “movement” in the words of one local partner. The “movement” has benefitted from strong support from the state legislature which has given $80M to the Washington Department of Ecology for the new state Floodplains by Design grant program.

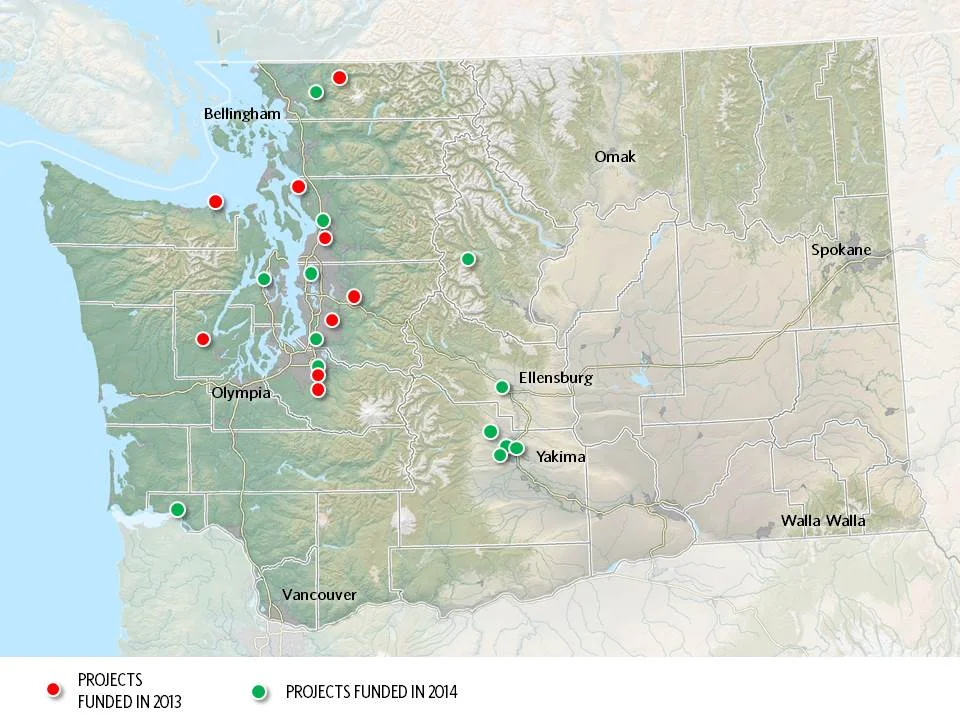

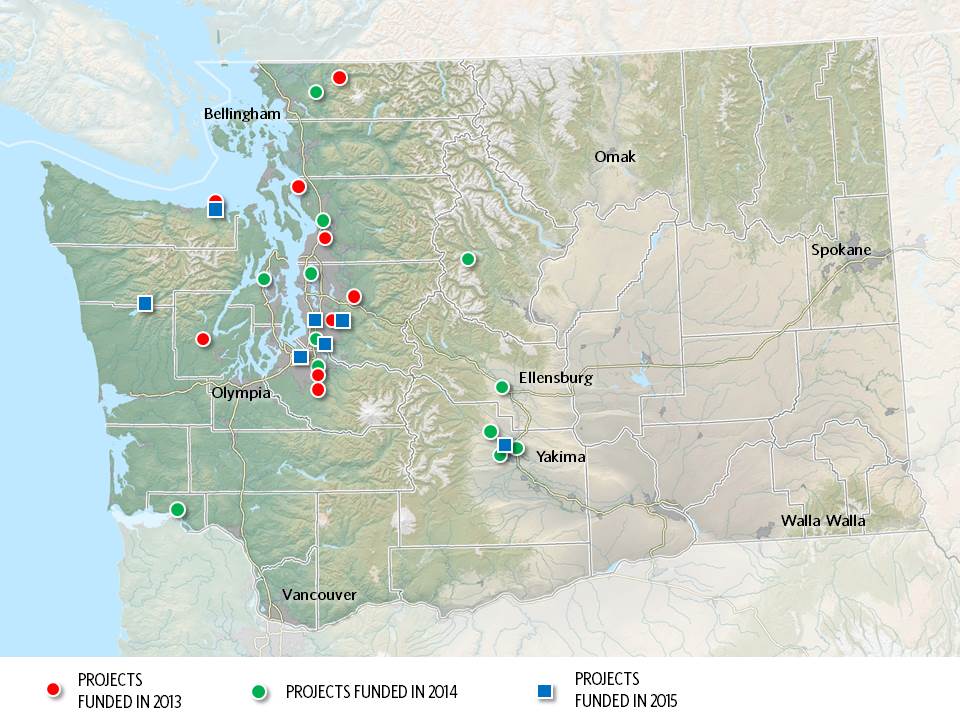

Erica Simek Sloniker, Cartographer and Visual Communications specialist for The Nature Conservancy, has produced a map series that documents the evolution from concept to movement. The initial 9 Floodplains by Design demonstration projects were funded by the state legislature in 2013. 2014 brought 13 more and 2015 another 7. Earlier this year, the Department of Ecology received 56 proposals for the next round of funding – an indication of the strong interest in joining this river revolution.

For more information visit www.floodplainsbydesign.org .

Floodplains: Revisited

Written & Photographed by Robin Stanton, Media Relations Manager

I revisited two Floodplains by Designs sites on the Puyallup River – the Calistoga Reach project in the town of Orting, and the South Fork project a few miles north and downriver from there.

These were both projects designed to re-connect the Puyallup River with its historic floodplain, provide more salmon habitat, and reduce the threat of flooding to people.

The Calistoga Reach project was completed in November of 2014—a week later the river hit a flood stage that previously had sent thousands of people fleeing from their homes. This time, Building Official Ken Wolfe said, “We didn’t have to deploy even one sandbag.” The river rose again in 2015, and again the town stayed dry.

Today, you can see the reclaimed natural areas that in times of flood give the river room to rise, and also offer refuge to juvenile salmon and other wildlife and walking paths for people.

The South Fork project is a new side channel for the river, again giving the water places to go when the volume is high, along with great salmon habitat. It’s being completed in stages, and by the time it’s finished, it will be a mile-long side channel, the longest on the Puyallup River. Engineers Jeffrey Davidson and David Davis helped me scramble all over the site, Pointing out new channels created by the river, engineered logjams that are evolving as the river runs through, and new gravel bars and sediment deposits brought down from Mount Rainier by the power of the river. Salmon are using the site, and they’ve seen black bear and deer out there as well.

It's remarkable to see how nature can come back and revive when you give it a chance!

Act Locally, Share Globally

Written by Bob Carey, Strategic Partnerships Director

Photographs by Flickr Creative Commons

Just a few short hours north of Seattle and set in the vast beauty of British Columbia, the Conservancy's Floodplains by Design program was the featured topic at a Canadian Water Resource Association workshop in Surrey. More than 30 WATER resource management leaders overwhelmingly responded positively when, at the close, their president asked if they were inspired by this work happening just south of the border. Their response was just as positive when asked if they’d like to see such a program in British Colombia and on the Fraser River.

The gathering of representatives from BC’s major cities, the BC government, the Fraser River Basin Council and environmental and academic groups represent those on the forefront of managing the Fraser River – the largest river in both BC and the Salish Sea, and the watershed with the highest flood risks in Canada. The strong affirmation that the “Floodplains by Design” approach makes sense and is applicable across the border made me proud to be part of a team leading the charge in making the region’s rivers more resilient for people and nature.

Restoring nature to address societies most pressing challenges is a prominent theme in the Conservancy's global conservation agenda. Our Floodplains by Design work in Washington is one of the best success stories of accomplishing this at a meaningful scale. Having secured $80M in new funding and helped catalyze 30 projects across the state, in which the restoration of nature and reduction of community risks are being pursued hand-in-hand, it’s clear that the approach can deliver tangible benefits to people and nature. That is why the invitations to share our story are numerous.

In addition to myriad audiences in Washington, over the last couple years our WATER team members have shared the Floodplains by Design story with a variety of national and international audiences, including: China Coastal Wetland Conservation Network (China), Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference (Vancouver, BC), American Planning Association (Phoenix), Association of State Floodplain Managers (Atlanta, Seattle), National Academy of Sciences (Washington DC), North American Water Learning Exchange (Pensacola, Phoenix) and the NW Floodplain Management Association (Post Falls, ID).

There are many great things about working for The Nature Conservancy, among them – the ability to innovate, the ability to scale up our work, and the ability to export beyond our borders.

It’s a recipe for making real change in the world.

Rebuilding an Estuary, Designed by Nature

Written by Beth Geiger, Northwest Writer

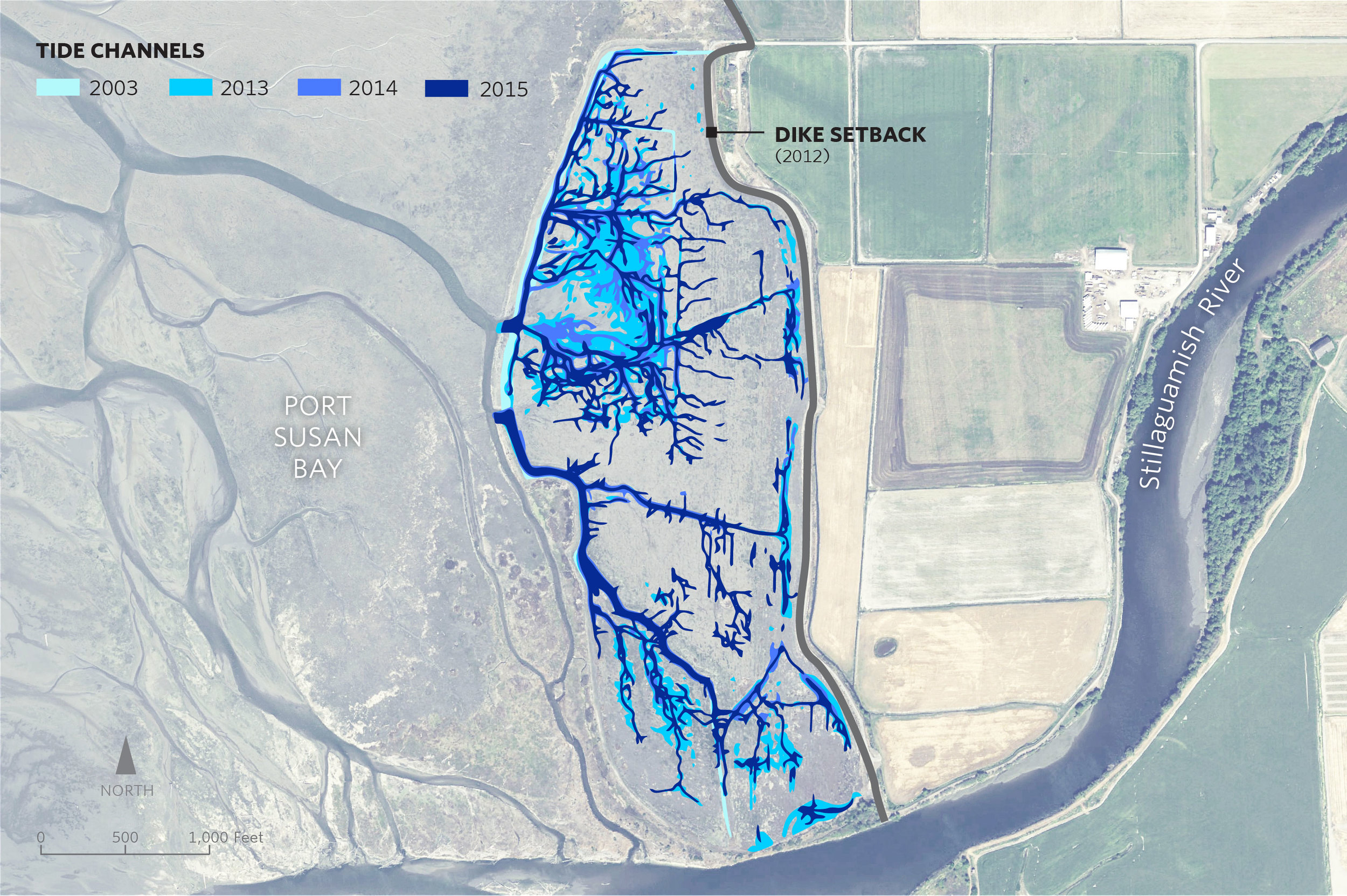

Graphics by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

A dramatic change has taken place in a marsh in Port Susan Bay, near Stanwood, Washington. In just three years the total length of tidal channels naturally increased tenfold, from 2,300 to 23,000 meters.

Tidal channels are key to a well-functioning estuarine ecosystem. Channels increase habitat diversity, which in turn increases species diversity. Juvenile salmon use the channels, dabbling ducks use them, and invertebrates that provide food for other species use them.

Scientists like Roger Fuller, an ecosystems ecologist at Western Washington University, are chronicling the new tidal channels, along with other changes here. Fuller says the development of so many new channels is “a big surprise.”

Marsh Revival

The new channels started forming in 2012, after The Nature Conservancy removed 7,000 feet of dike that had separated the 150-acre marsh from the rest of Port Susan Bay since the 1950s. The dike removed had over time diverted Hatt Slough, the Stillaguamish River’s biggest distributary channel, south where it spills into Port Susan Bay. That dike had also cut the marsh off from its main source of fresh water and sediment.

With marsh, river, and Puget Sound connected again, natural processes took over. Critical estuary habitat quickly began to be rebuilt. A natural revival was underway.

The channels are a big part of this revival. “Channels build connections, creating the intimate links that tie the marsh, tide and river together,” Fuller explains. “They serve as the trade routes of the estuary, funneling water, sediment, fish, and the organic matter that fuels the entire estuarine food web back and forth between marsh and tidal flat.”

Sound Science

Supported by the Conservancy, Fuller and other scientists including Greg Hood with the Skagit River System Cooperative, and Eric Grossman, Christopher A. Curran and Isa Woo from the United States Geological Survey have been studying the channels and other ways that this estuary is recovering.

The researchers analyze before and after data, and compare the restoration area to a nearby reference marsh which has never been diked. They measure suspended sediment, water temperature, salinity, current, as well as topographic and ecological changes.

New tidal channels aren’t the only “before and after” they’ve seen. When the dikes were in place, the area inside them had been starved of its natural influx of sediment from the Stillaguamish River. The estuary had subsided until it was a meter lower than the surrounding tidelands in some places. It functioned more like a pond than a dynamic estuary. For example, there was no access or protected estuarine habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon transitioning from the Stillaguamish River into Puget Sound.

With the dike removed scientists have recorded a measurable rise in the height of the marsh. During those years the sediment delivered to PSB was unusually high in part due to the March 2014 Oso landslide. However, the data suggest that even if the marsh gets half as much sediment in future years, it may still rise fast enough to keep up with the rising sea level, estimated to be an average of about 24 inches by 2100.

Lessons from Nature

Fuller says that being surprised by nature here isn’t all that unexpected. “The one thing I knew before the restoration was that I would be surprised by the changes triggered by the restoration,” he says. “There's been so little research on restoration in northwest estuaries that I knew it would be really interesting to watch it unfold.”

The restoration project is part of the Port Susan Bay Preserve, which includes 4,122 acres of estuary that the Conservancy acquired in 2001. The science being conducted here reaches much further than the Preserve itself. Along with learning new lessons, we are applying scientific concepts and models honed under this and other Conservancy projects such as Fisher Slough.

Together, these projects demonstrate that carefully planned restoration can have complementary, not conflicting, benefits for people, salmon, farms, and wildlife. The Conservancy-led Floodplains by Design provides the partnerships and funding that ensure these lessons can extend to restoration projects all over Puget Sound.

As a result of diligent science and critical partnerships like this, we are learning how to make Puget Sound more resilient as climate changes, and sea level rises.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK IN PUGET SOUND

LEARN HOW CLIMATE CHANGE WILL AFFECT THE REGION AND WHAT WE'RE DOING TO ADAPT

Packing Passion: Community Sits at Heart of Floodplain Planning

Written by Jeanine Stewart, Volunteer writer

In the political world of environmental activism, so often the tendency is to side with one issue at all costs, destroying any and all interests that get in the way.

That’s not the case for The Nature Conservancy’s Puget Sound community relations manager Heather Cole, who joined last October. She works with communities to find environmentally sound solutions to Puget Sound major river systems.

The major question she’s tasked with? How to help communities in Puget Sound develop floodplain management visions – minimizing flood risk in areas prone to flooding while also improving ecosystem benefit, such as improving salmon habitat and water quality – that take into account the often-conflicting interests of a diverse list of stakeholders.

“Local jurisdictions, , tribes, farmers, diking districts, for example – they all have competing values for how they want to manage the same piece of land,” Cole said. “The question is, how do we integrate all those multiple values of the local community?”

Read more about the Conservancy’s work in floodplains here.

Rapid population growth necessitates swift movement on these discussions. The Puget Sound region’s population will likely grow 8 percent between 2014 and 2020, and 28 percent by 2040, according to the Puget Sound Regional Council.

This puts pressure on local jurisdictions to allow more construction. Meanwhile, farmers face a daily struggle to make a living from the same land. And the region’s iconic salmon need habitat and clean water. All these needs must be balanced with those of flood safety, Cole explains.

She’s now hard at work on the first step of balancing these interests, identifying the barriers that get in the way of conservation planning by collaborating with all the parties involved, including local leaders.

Working through conflicting interests to find common ground is Cole’s specialty. She brings nearly a decade of experience working for the state of Washington on natural resource issues, doing research, planning and community development. She also received a master’s in international development and environmental analysis in Australia.

Cole sees each group’s interests as a key piece of the puzzle rather than barriers to a tunnel-vision view of the solution.

“Coming from a natural resources perspective and working in the natural resources field for a number of years, you come to realize that these issues can’t be solved with a technical silver bullet,” Cole said. “We have to understand the people landscape. People are part of the problem, and they are part of the solution.”

This simple and clear-headed approach is a calming reprieve from the complex and lofty goals Cole has her eyes on.

Asked to summarize her work, she says it focuses on “integrated floodplain management where local groups can find agreement on strategies and actions for our rivers that have multiple benefits, such as improving flood safety, agriculture preservation and restoring floodplain connections that support endangered species like salmon; while also bringing in climate change information so that we are making wise investments today that will survive in a changing climate fifty to a hundred years from now.”

Integrating Climate Into Floodplain Planning

Written by Robin Stanton, Media Relations Manager

Photographs by Chris Hilton, Grant Fundraising Director

Floodplain leaders from around the Puget Sound region gathered today for a workshop on advancing floodplain restoration, including a new focus on integrating climate change data.

“There’s a big gap between what we know and what we’re doing about it,” says Julie Morse, the Conservancy’s regional ecologist.

“It’s not unique to Puget Sound, we find it all over the country.”

At today’s workshop, floodplain leaders will begin to develop strategies for including climate impacts into the work they’re already doing.

The Conservancy has been working with the University of Washington Climate Impacts Group to take its recent Puget Sound Climate Synthesis Report and turn it into information that is really useful to city, county and state leaders grappling with these issues on the ground. Today’s workshop is a chance for floodplain leaders to work hands on with this information.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR FLOODPLAINS WORK

New tool can help plan for future flooding

Written by Kris Johnson, Senior Scientist, The Nature Conservancy

Flooding is increasingly becoming a fact of life along the Snohomish River. In early December the severe flooding in the cities of Snohomish and Monroe inundated homes and farms and closed roads and a city park. For residents in the area it was déjà vu all over again, as just weeks before some of the same areas experienced a separate major flooding event. Clearly, managing flood risk along the Snohomish, and throughout western Washington, is challenging yet essential to the lives and livelihoods of millions of people.

And climate change is compounding this problem: warmer temperatures are leading to sea level rise and higher tides, and more winter precipitation is falling as rain rather than snow, causing flashier flows in the rivers. Understanding how flood risk is changing and incorporating best-available information into planning and decision-making is crucial for communities in Puget Sound.

With this in mind the Nature Conservancy led a recent pilot project to both evaluate how climate change might impact flooding and then provide this information to local decision-makers. In partnership with the University of Washington Climate Impacts Group and West Engineering we assessed how varying scenarios of climate change could alter flooding in the Lower Snohomish River and cause potentially greater impact to farms and buildings and infrastructure.

This analysis suggested that in just a few decades what is currently considered a “100-year” flood could be much more severe and could inundate part of I-5 near Everett and cause nearly 20% more costly property losses (see image).

To make this information useful and readily available we created new Floodplains by Design ‘app’ on the Coastal Resilience decision support tool so that local partners with the Sustainable Lands Strategy in Snohomish County could integrate maps and images of potential flooding into their project planning and decision-making process.

Managing increasing flood risk while sustaining high-value agriculture and also restoring salmon populations and protecting the environment will be a major challenge in Puget Sound in the 21st century. Rigorous science and sophisticated tools, like those developed by The Nature Conservancy for the Lower Snohomish River, can provide local communities with the best-available information that can help them plan accordingly.

10 Months and 2 Days on the Dungeness River

Written and Photographed by Randy Johnson, Habitat program manager, Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe

Aerial Photographs provided by John Gussman

Since the first of February 2015, four floods have rumbled down the Dungeness River. The first one damaged the old creosoted RR trestle and closed the Olympic Discovery Trail (ODT). The three floods in the past six weeks have occurred while we've been building the new pedestrian bridge that will replace the trestle. During the floods, the river has migrated 230 feet west. Had the trestle not been removed, at least 15 pile bents - 75 creosoted piling, creosoted timbers, and bridge decking - would have been knocked down and strewn all the way from the Dungeness River RR Park to Dungeness Bay.

It was a given that the Tribe would replace the trestle's functions for users of the Olympic Discovery Trail. 10 Months and 2 days later, the entire 585' of trestle and its dripping creosote are gone from the floodplain forever and 720 feet of salmon friendly and river worthy pedestrian bridge is connected to the ODT. All 750 feet of new bridge are now in place, and just a few relatively minor tasks remain. The construction access road is being removed, and by the end of today both floodplain channels will be flowing free again. You can look forward to the ODT being reopened soon.

Floodplains by Design funding was a perfect fit for this project because of the program’s focus on reconnecting rivers to their floodplains for fish and flood risk reduction, and the additional community benefit of recreational access.

Thank you everyone for your role in making this bold vision a reality.