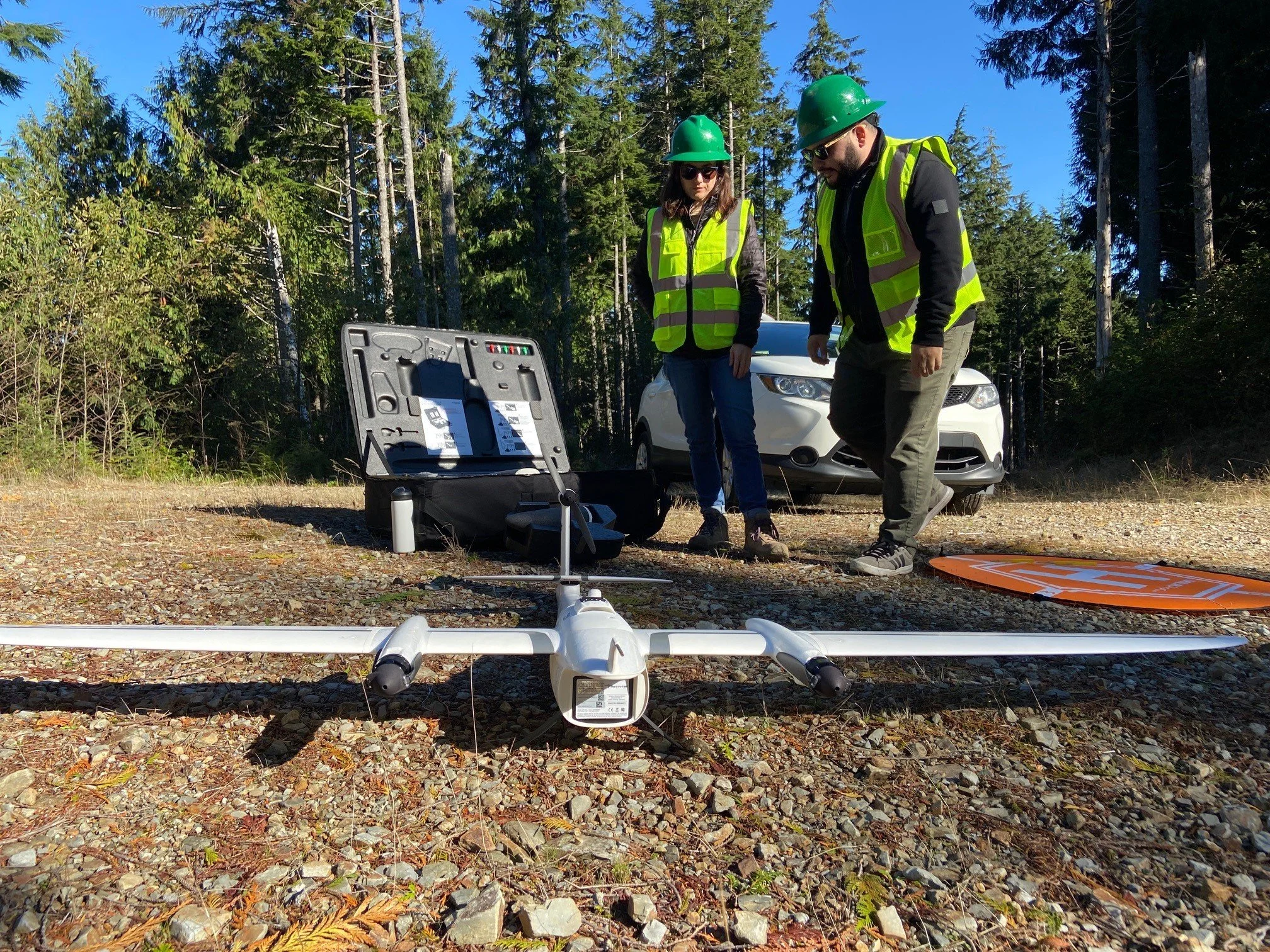

Drones have emerged as a groundbreaking tool extending our reach beyond the limits of human exploration. While many are familiar with seeing the possibilities in adventure photography or package delivery, the use of drones in conservation has become increasingly creative for those both out in the field and in the lab.

When Restoration Gets Explosive

Using dynamite for restoration may seem like a paradox, but at TNC’s Port Susan Bay Preserve, we explored dynamite as a way to create estuary channels. The inspiration behind this method was to see if explosives could reduce the ecological impact of channel creation in comparison to using heavy machinery.

Taneum Watershed Trails: A Restoration Story

Catching Animals... on Camera in the Ellsworth Creek Preserve

Where the Water Meets the Sea

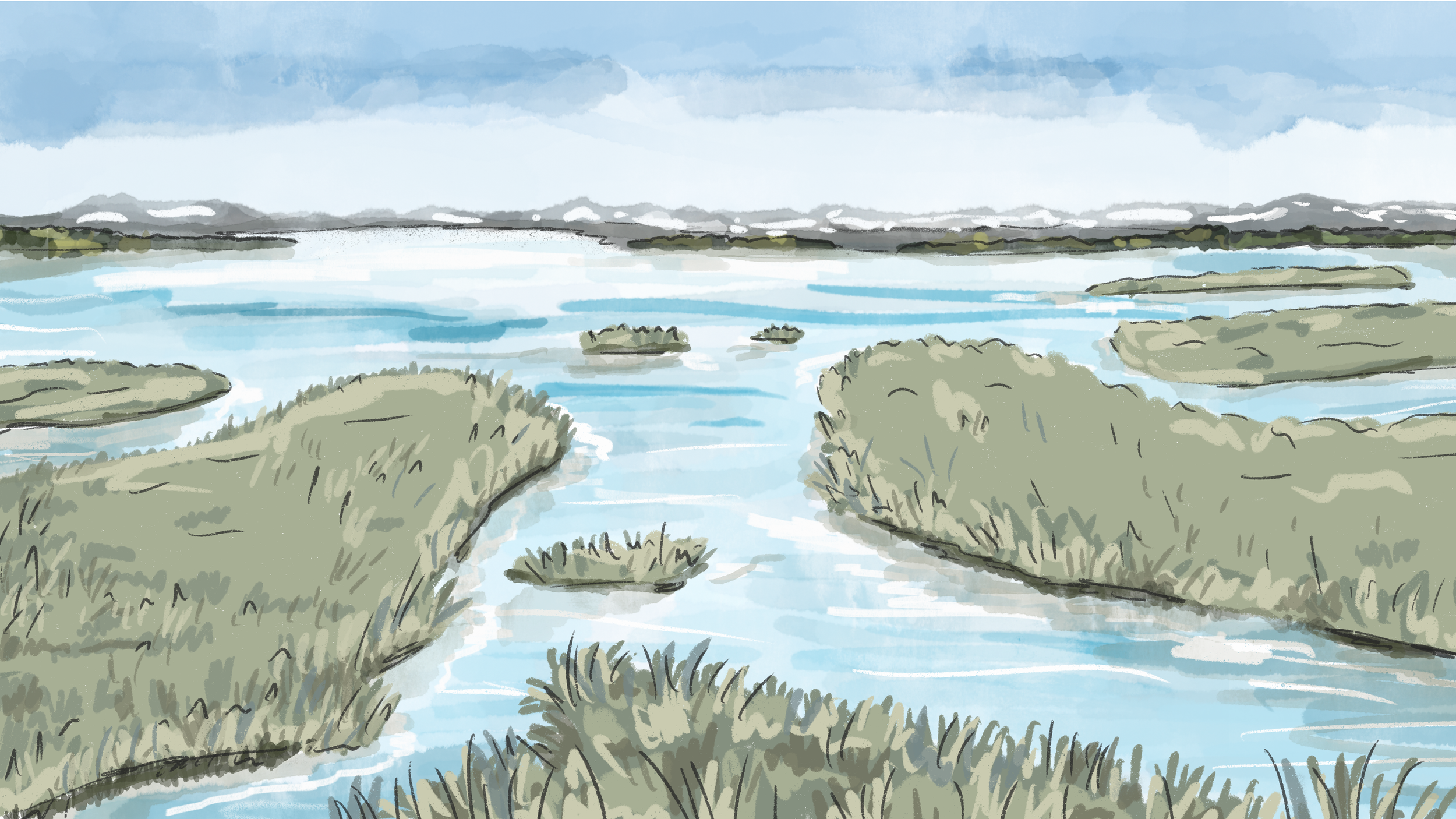

KCTS9-Crosscut interviews Dr. Emily Howe, Aquatic Ecologist at The Nature Conservancy for their “Human Elements” series where Emily talks about her personal connection to marshes and how she is working to restore these unique—and messy—ecosystems.

Keep Washington Evergreen

Mission Moment: Wonder and Respect for a Life-Giving System

When the Forest Flies

In September 2020, thanks to the funding from the state Washington State Coast Restoration and Resilience Initiative, The Nature Conservancy completed a step towards whole system restoration of our coastal streams on our Olympic Forest Reserves. The grant funded a series of thinning, planting of native riparian trees, weed treatments, and, most impressively, the installation of large woody debris jams "log jams" in Shale Creek, a tributary of the Clearwater and Queets River. See helicopters placing log jams in the river

Puget Sound Science - A Human-Centered Approach

We are all the end users of science for the Puget Sound. No amount of money or science alone is going to protect and restore the Puget Sound. But, people changing their behavior will. Design the right tools that connect people to what they care about in to the Puget Sound each day and people will change. Design thinking starts with learning what they care about.

Hurst Creek Log Jams Quickly Show Benefits for Salmon

Do you have launching toe? Probably not, unless you’re a levee!

Restoring America’s Forests Annual Meeting

Written and photographed by Ryan Haugo, Washington Senior Forest Ecologist

At the end of September several of us had the pleasure of representing the Washington chapter at the Conservancy’s annual North America “Restoring America’s Forests” conference in northern Arizona. Restoring America’s Forests is a formal network of over 13 demonstration landscapes across North America where the Conservancy is pursuing conservation through collaborative, ecological restoration on our national forests. Within Washington, the Restoring America’s Forests network incorporates both the Tapash Sustainable Forest Collaborative and the North Central Washington Forest Health Collaborative.

Northern Arizona is home to one North America’s largest, most ambitious ecological restoration efforts – the Four Forests Initiative (better known as 4FRI). Here the Conservancy has been instrumental in driving a science based approach to the restoration of millions of acres of dry, fire-adapted forests that are suffering from over a century of wildfire suppression.

The similarities (and differences) between the forests of Northern Arizona and eastern Washington are striking. Just as in eastern Washington, the dry forests of northern Arizona have experienced record breaking wildfires in recent years. The dry forests of northern Arizona are adapted to (and depend upon) frequent, low severity fire. Many of the recent “mega-fires” however, are well outside the range of conditions to which the forests are adapted. These fires threaten not only local communities but also the abundant fish and wildlife habitat, clean air and water, and recreational opportunities that draw people from across the globe to northern Arizona. Similar to eastern Washington, restoring the health and resilience of these forests depends upon using a combination of tools including mechanical thinning (logging), controlled burning, and managed wildfire to thin out the incredible density of small trees that have grown up in the absence of natural wildfire.

Finally, the economic viability of restoring dry forests in both northern Arizona and eastern Washington depends upon a forest products industry that has largely vanished from the local landscapes in recent decades. The differences are important to understand. The dry forests of northern Arizona are simpler, primarily with one tree species (ponderosa pine), and are typically much flatter. Both of these factors ease the implementation of ecological restoration treatments in comparison to eastern Washington.

A highlight of our 4FRI field tour including seeing first-hand the ingenious in-cab tablet technology that TNC has helped to develop. The tablets are designed to increase the efficiency of implementing ecological prescriptions during forest thinning projects. We also had the opportunity to visit the newly developed NewPac Fibre sawmill in Williams, AZ. This sawmill processes the trees harvested during restoration thinning and provides sustainable employment opportunities for local communities.

Most importantly however, was the opportunity to share successes, failures, and lessons learned amongst all of the Restoring America’s Forests landscapes. During these meetings we dive in deep to the policy, science, and partnership issues facing our work to restoring our National Forests. The Restoring America’s Forests network provides the opportunity to make and maintain personal connections between a forest ecologist in Washington State, a forest policy expert in Washington DC, a fire manager in Arkansas, and a forest manager in Arizona. These are powerful relationships and help to make the Conservancy such an effective conservation organization.

Learn more about our forestry work

Rolling Back the Pavement

Written by Tammy Kennon

Photographed by Melissa Buckingham, Pierce Conservation District

Pavement does not have to be permanent. The Puget Sound Conservation Districts, a collaboration of the Puget Sound’s 12 districts, reminds us that it’s possible to bring nature back into our urban landscapes.

Tacoma’s Hilltop neighborhood has reclaimed a derelict, crumbling parking lot and gained a multi-use green habitat. The project, completed in June, now serves dual use as a community gathering space and a natural filtration system for otherwise polluted runoff. The transformed space now filters on-site more than 130,000 gallons of polluted runoff a year.

Thanks to its natural beauty, economic growth and the thriving tech industry, the Puget Sound region is one of the most rapidly urbanizing areas in the nation. Our population grows by more than 200 people every day and by some estimates will top 7.5 million by 2030. Often, this growth puts our green spaces in a losing tug-of-war with urban development. Sprawling pavement, rooftops and roadways send increasing levels of polluted runoff into our vital waterways, creating one of our most urgent environmental challenges.

Reclaiming even small patches of pavement and restoring nature’s filtering systems can have a significant effect in mitigating stormwater pollution, while at the same time reenergizing urban neighborhoods and improving quality of life within our communities.

For the Tacoma Hilltop project, the Pierce Conservation District (PCD) enlisted more than 100 members from the community to help select a site and participate in its transformation.

“We partnered with Tacoma’s Healthy Homes Healthy Neighborhoods program to identify unfunctional space,” said Melissa Buckingham, Water Quality Improvement Director of the Pierce Conservation District. “Feast Art Center was moving into the area and wanted to create an outdoor community space. It just all came together.”

With funds from Boeing and The Nature Conservancy, the Feast Arts Center, an art school and gallery, converted 4,500 square feet of derelict pavement at south 11th and south Sheridan into a vibrant community gathering space featuring an outdoor silent movie theater, rain garden and a green multi-use lawn for events. The perimeter includes a drivable area to accommodate a variety of community events that might utilize food trucks or blood drive vehicles.

“The building and the lot had been a vacant eyesore for many years, so many in the community are grateful for the change,” said Todd Jannausch, co-owner of Feast Arts Center. “We use the space to host a variety of free events, classes and performances for the community.”

Bringing nature back into our urban environment can do more than just energize the neighborhood. A growing body of research suggests that living near green space inspires physical activity, improves neighborhood safety, boosts the economy and helps children learn. The bottom line: It’s easier being green!

The success of the Feast Arts Center depave project is a welcome reminder that we can reclaim a natural habitat in the urban environment, proving that humans and nature can thrive together in the same space.

Celebrating Fir Island Restoration

By Jenny Baker, Senior Restoration Manager

Photos by Jeanette Dorner; Alison Hart, Washington department of Fish and Wildlife

The Fir Island Farm ribbon cutting was a wonderful event celebrating project completion with the large community of folks who have helped usher the project to the finish line over the last seven years.

This 131-acre project restores habitat for salmon, improves flood protection and drainage infrastructure for agriculture and provides public access at the intersection between the fertile farms of Fir Island and the salty marsh beyond.

See the breaching of the dike that let the tide back in after 100 years.

A new dike keeps neighboring farmland dry, while we still make room for thousands of juvenile salmon. Read more about the project here.

Central Cascades Forest Restoration Project Honored

Photographed by John Marshall

A groundbreaking forest restoration project led by The Nature Conservancy here in Washington has been honored with the SFI Leadership in Conservation Award at the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) 2016 Annual Conference.

“At its heart, the Manastash-Taneum Resilient Landscape Restoration Project recognizes that good forest management, which includes responsible harvesting, allows fire-, insect-, and disease-resistant forests to thrive and also benefits a diversity of species,” said the award announcement.

"We are so pleased to recognize the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the Yakama Nation, both SFI Program Participants, and their partners the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, The Nature Conservancy, and the U.S. Forest Service," said Kathy Abusow, President and CEO of SFI Inc.

"These forests will benefit if they are managed in ways that allow them to better tolerate wildfires. Responsible harvesting, followed by controlled prescribed burning, should help reduce crown fires, which are more dangerous and difficult to control. This is a practical way to help mitigate some of the damage that climate change is expected to cause," said Laura Potash, coordinator for the Tapash Sustainable Forests Collaborative, which brings all the project partners together.

Read the full press release here

Read more about the project here

Volunteer Stories: Supporting the Pacific Northwest

Written by Jill Irwin, Volunteer

Photo Credit: Milo Zorzino

With explosive growth in the Pacific Northwest—especially in Seattle and Portland—more and more people are adding to the stresses on our rich and complex natural environment. How about pitching in to help keep this place beautiful and restore damaged habitats?

Recently a group I'm involved with spent part of a day volunteering with the Nature Conservancy at one of their sites in the Puget Sound region. (One of the cool things about helping out the Nature Conservancy is that their sites are often scenic and rarely open to the public. Hence, no crowds.)

On a breezy Sunday morning, about 10 of us, an eclectic collection of Zen Buddhists, a retired teacher, father and son duck hunters, conservation biologists, and more, met up near and carpooled to a private property to access the Livingston Bay Pocket Estuary site on Camano. Our goal for the day: pull invasive Scotch broom, which changes the chemical composition of soil and crowds out native plants.

Our Nature Conservancy coordinater for the event, Lauren Mihel, gathered us in a circle for introductions before heading down through the woods to the beach.

"What's your name and what are you excited about for fall?" she asked as an ice breaker.Our responses varied from "making soup again", "fall colors," "cooler weather and rain," and mine: "hiking to see the golden larches." Then we headed down to the estuary with tools for uprooting the Scotch broom and big plastic bags for picking up trash.

We spent a few hours uprooting most of the Scotch broom we could spot, and some of us walked the beach looking for trash.

On the outside of the pocket estuary, exposed to the ebb and flow of the tides, a lot of trash had washed up—plastic bottles, plastic lighters, plastic bags, a few stray shoes, old tires, bits of plastic, and even a big plastic trash can.

I filled a big bag until it got too heavy to squeeze in anything else. Sadly, this much trash, predominantly plastic refuse, is now common, even on wilderness beaches and shorelines. So there are plenty of opportunities to help clean up on your own, too.

We finished up a bit earlier than the allotted time, and gathered for Lauren and fellow coordinator Joelene Boyd to talk a bit about the site, ongoing restoration efforts here that began in 2012, its value as refuge for juvenile salmon, and the Nature Conservancy's programs in general. It's all part of a larger restoration effort in the area.

In a sweet gesture, Lauren passed around tins of excellent chocolate chip cookies she made for the group. And of course it was a beautiful, peaceful place to spend several hours on a sunny Sunday.

Overall it was a thoroughly enjoyable and rewarding day well spent. I met good people, got better acquainted with people I already knew, felt a sense of accomplishment, was outside moving in fresh air, and learned more about our precious Salish Sea ecosystem.

While there are many options for volunteering with the Nature Conservancy, there are lots of other organizations that could use your help too. Here are a few:

The U.S. Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest needs volunteers for many things such as trail maintenance and youth programs.Conservation Northwest has many volunteer needs for things like monitoring wildlife and planting native trees. EarthShare Washington and Oregon have a variety of volunteer and organizational needs. Portland Audubon and Seattle Audubon have active and well-organized volunteer programs. Sierra Club offers lots of ways to get involved. Washington Trails Association has regular work parties. The Portland-based Mazamas has lots of volunteer needs.

I could go on and on, although time doesn't permit it right now. Maybe you would like to suggest some ways to volunteer and your favorite environmental organizations by leaving a comment below! Or let me know if you'd like me to contact you with more ideas. Because it's important!

The Volunteer Crew

Seattle-born Jill Irwin blogs about the environment and everyday adventures in the Pacific Northwest. Read more of her stories on her blog Pacific Northwest Seasons

Creating a Movement for Our Rivers and Floodplains

Written by John Lombard, Lombard Consulting

In the ten years since my book, Saving Puget Sound, came out, Floodplains by Design is the most impressive regional initiative that I have seen for Puget Sound conservation. Focusing on floodplain restoration, it is tackling one of the most important parts of the landscape for conserving Puget Sound as an ecosystem, serving as a model for how we might address other key issues, such as the Puget Sound shoreline and stormwater management. Even more impressive, while starting in Puget Sound, Floodplains by Design has quickly grown into a statewide initiative.

Taking a multi-benefit approach, Floodplains by Design recognizes that virtually by definition any major action in floodplains affects multiple interests—agriculture, salmon recovery, flood hazards (locally, downstream, and even sometimes upstream), and often a significant amount of development and infrastructure. We have traditionally funded actions in the floodplain from different pots focused on these different interests, which tends to lead to partial solutions, conflicts with the other interests, and insufficient resources to take a more holistic view—even when that holistic approach is cheapest and better for everyone in the long run.

Floodplains by Design is a model for how to approach these types of issues more effectively. It is a perfect example of a role that The Nature Conservancy can fit extremely well—facilitating a partnership that takes a creative approach to a common problem across the region and state, and attracting legislative and funding support because it offers real solutions and brings communities together.

John Lombard is the owner and principal of Lombard Consulting. He is the author of the book Saving Puget Sound which won the Haig-Brown Award for environmental writing from the North Pacific International Chapter of the American Fisheries Society.

Visit http://www.floodplainsbydesign.org/ to learn more

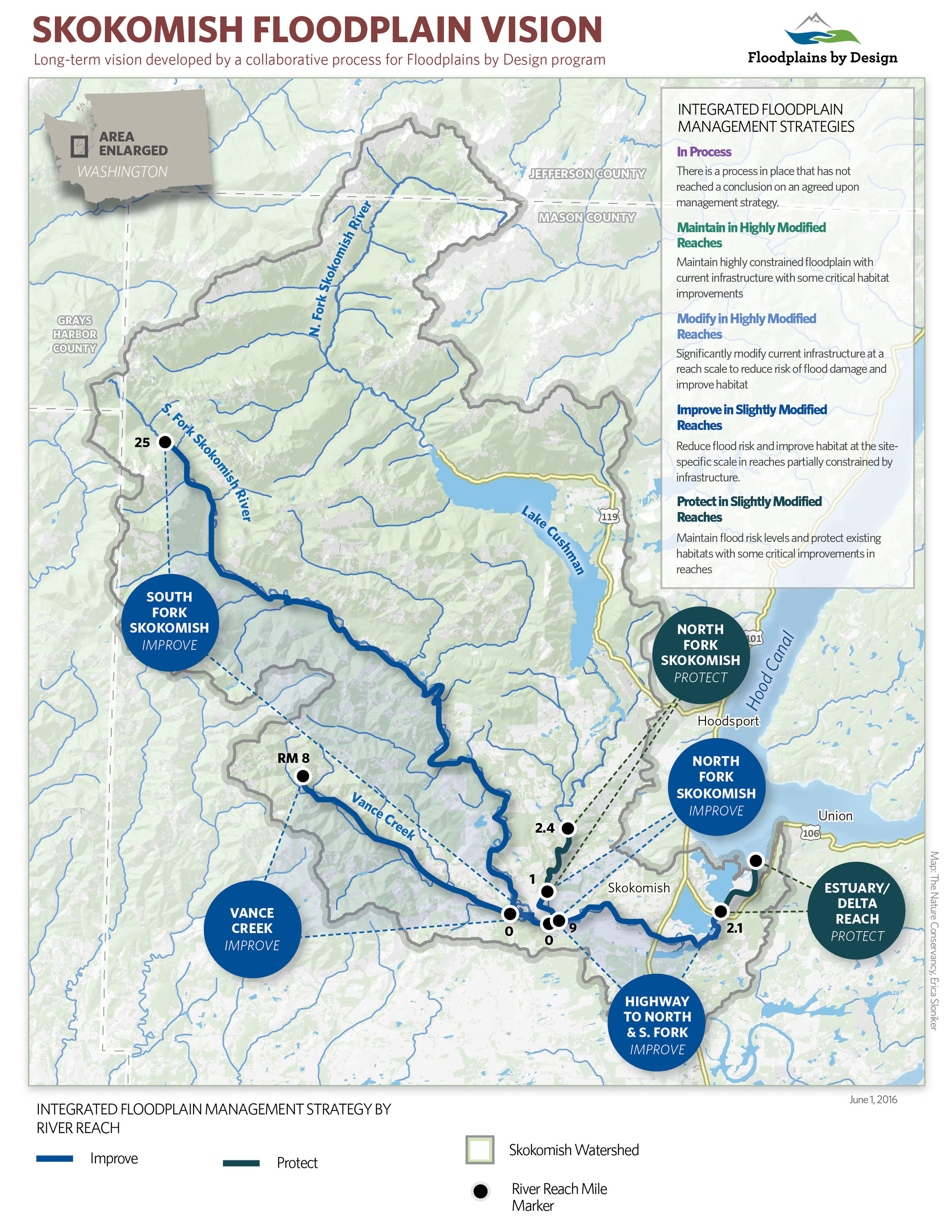

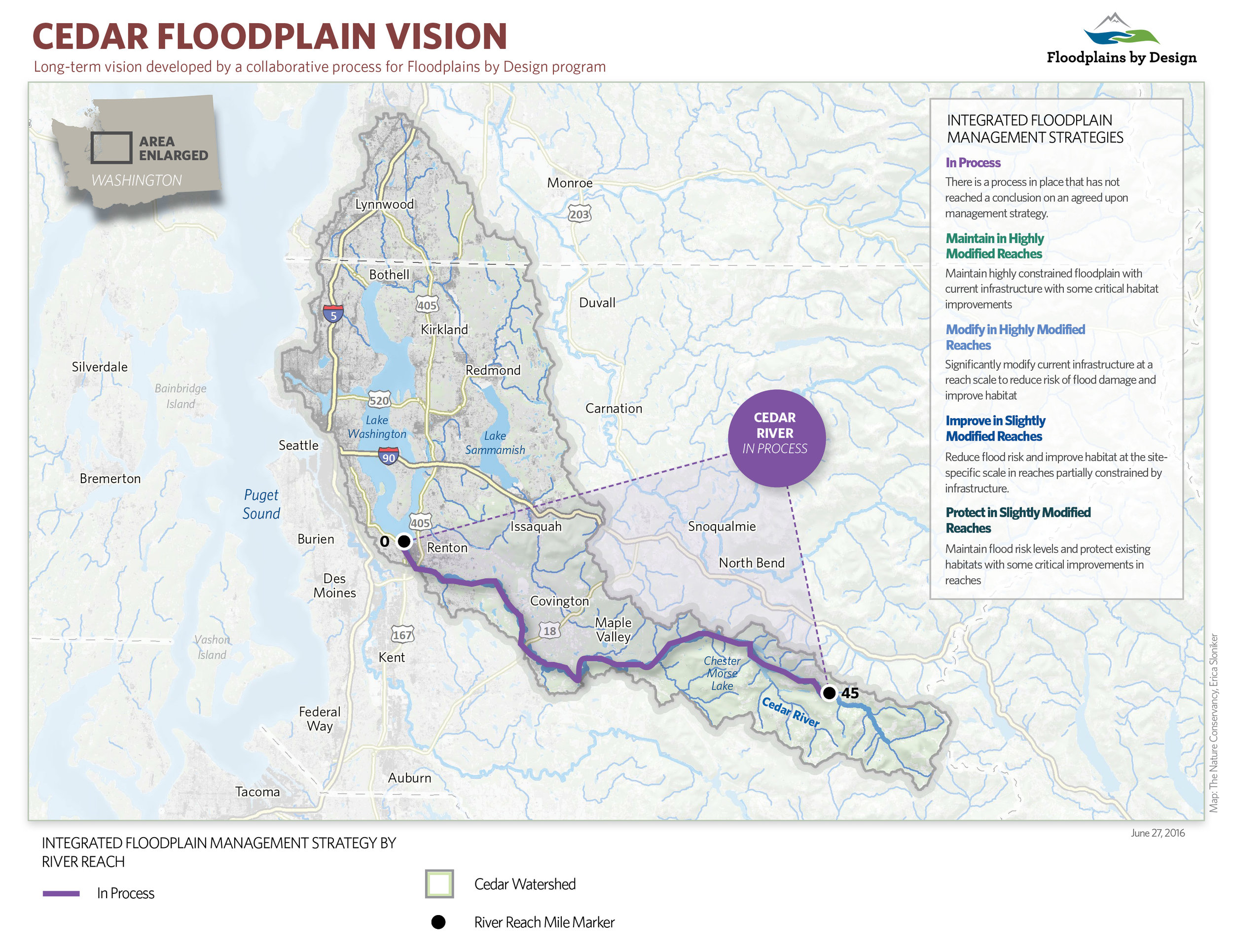

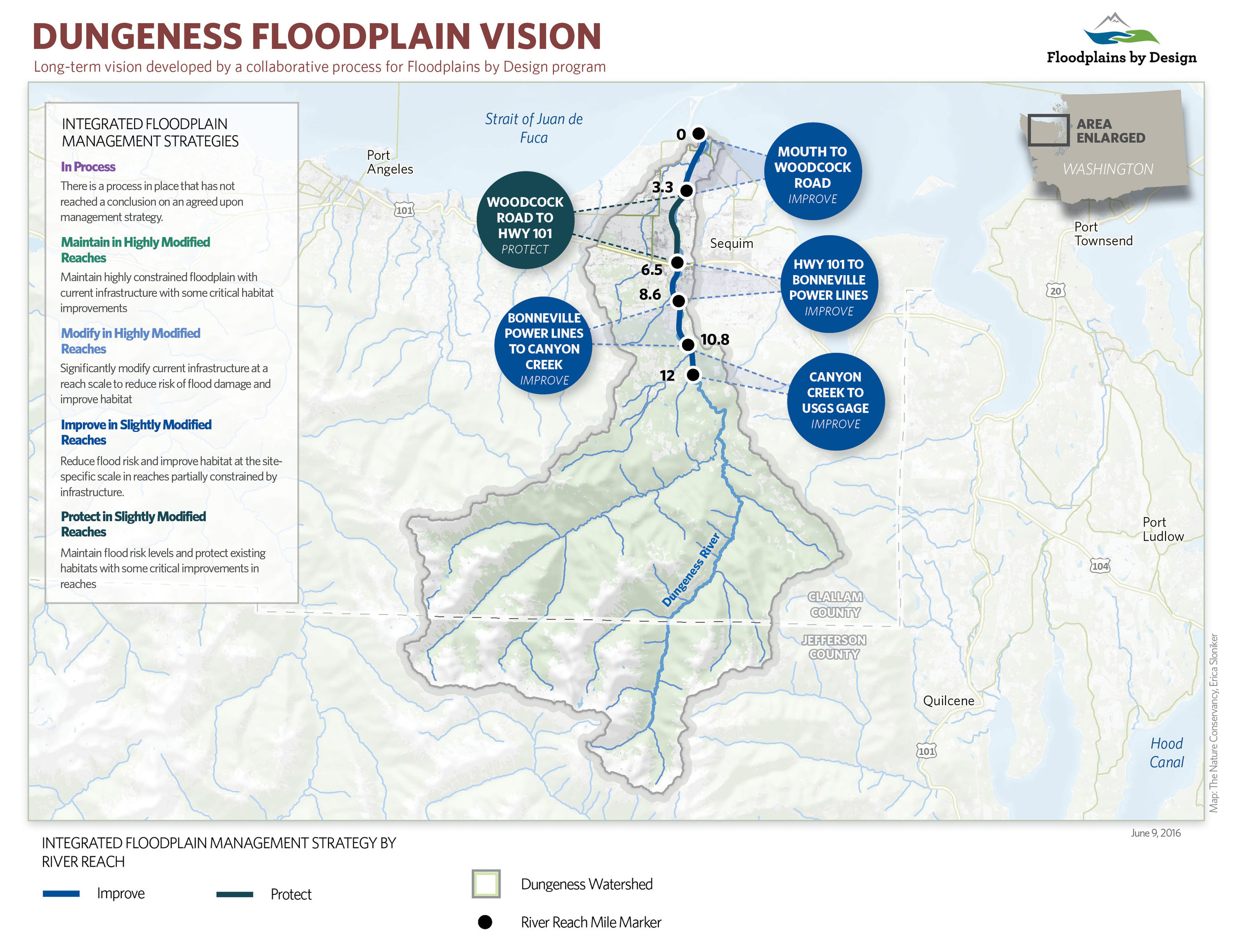

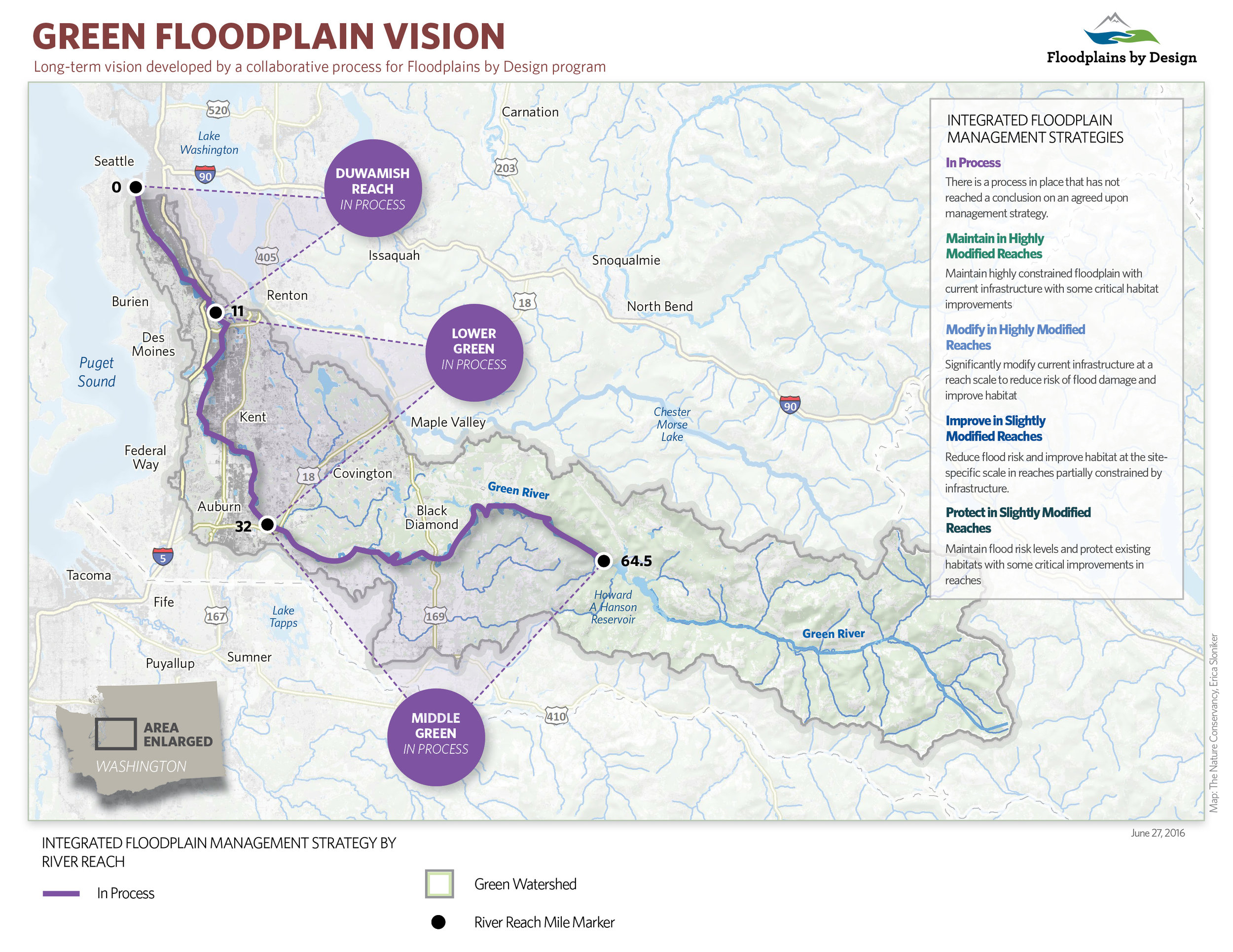

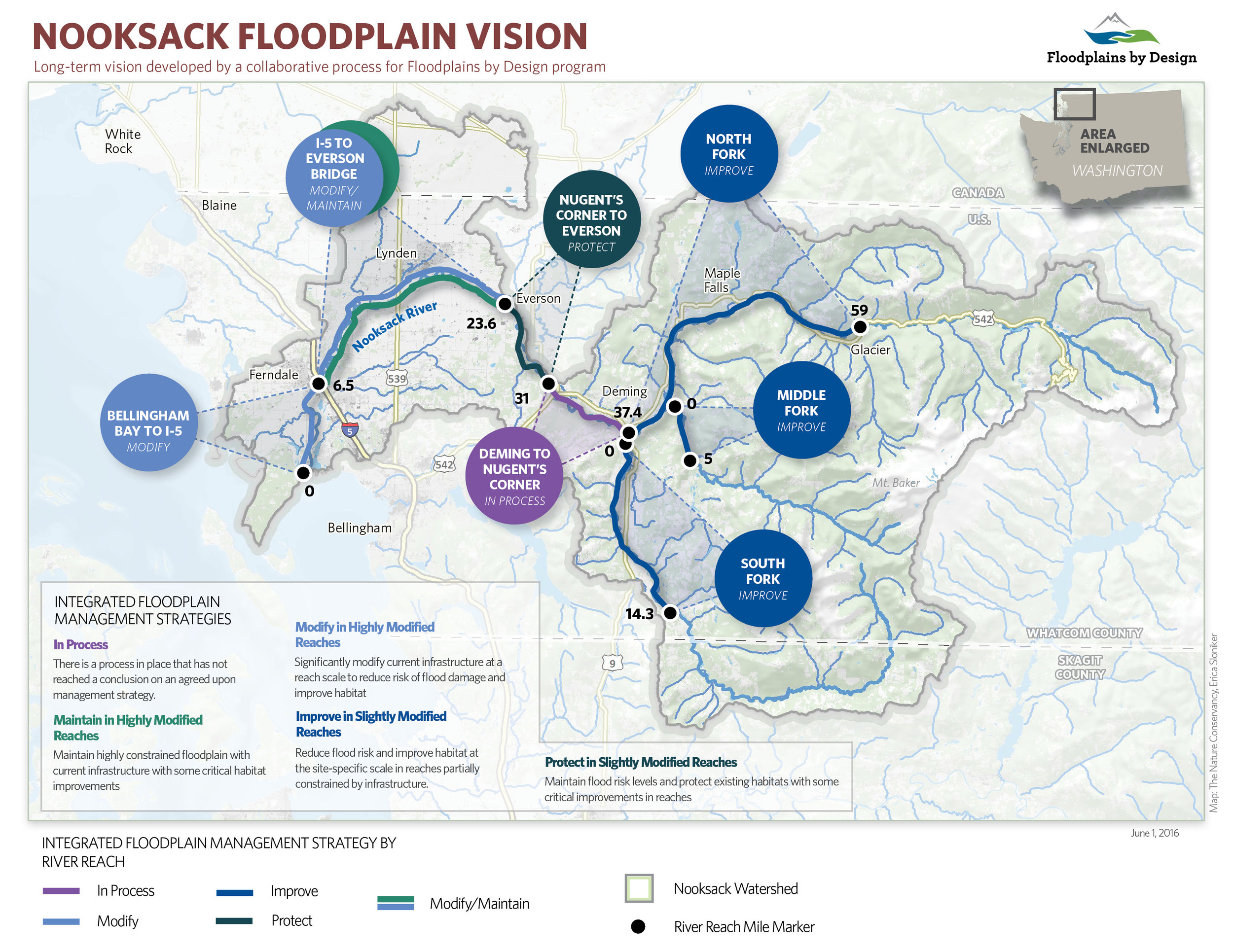

Revisioning our Rivers: Innovation through collaboration

Written by: Bob Carey

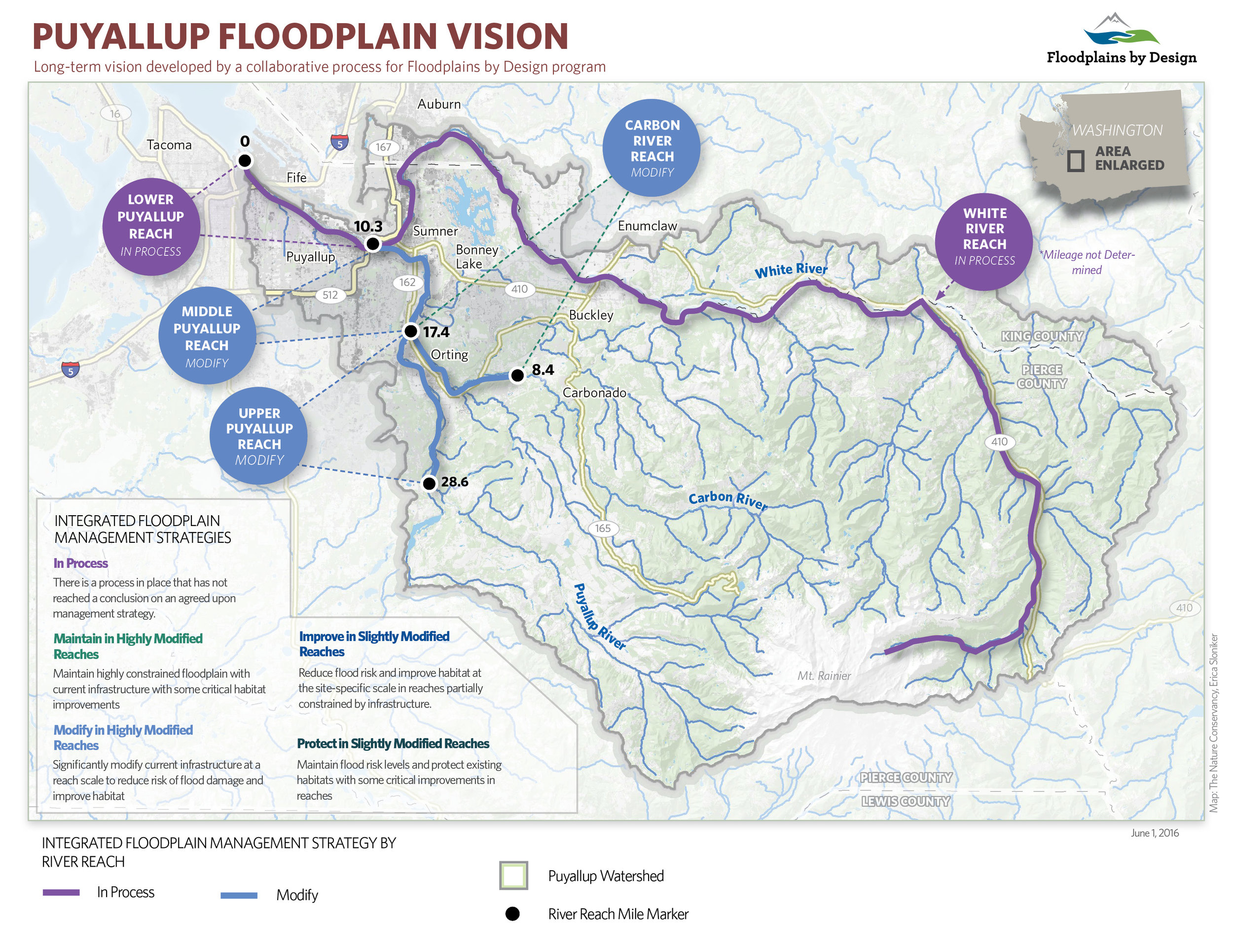

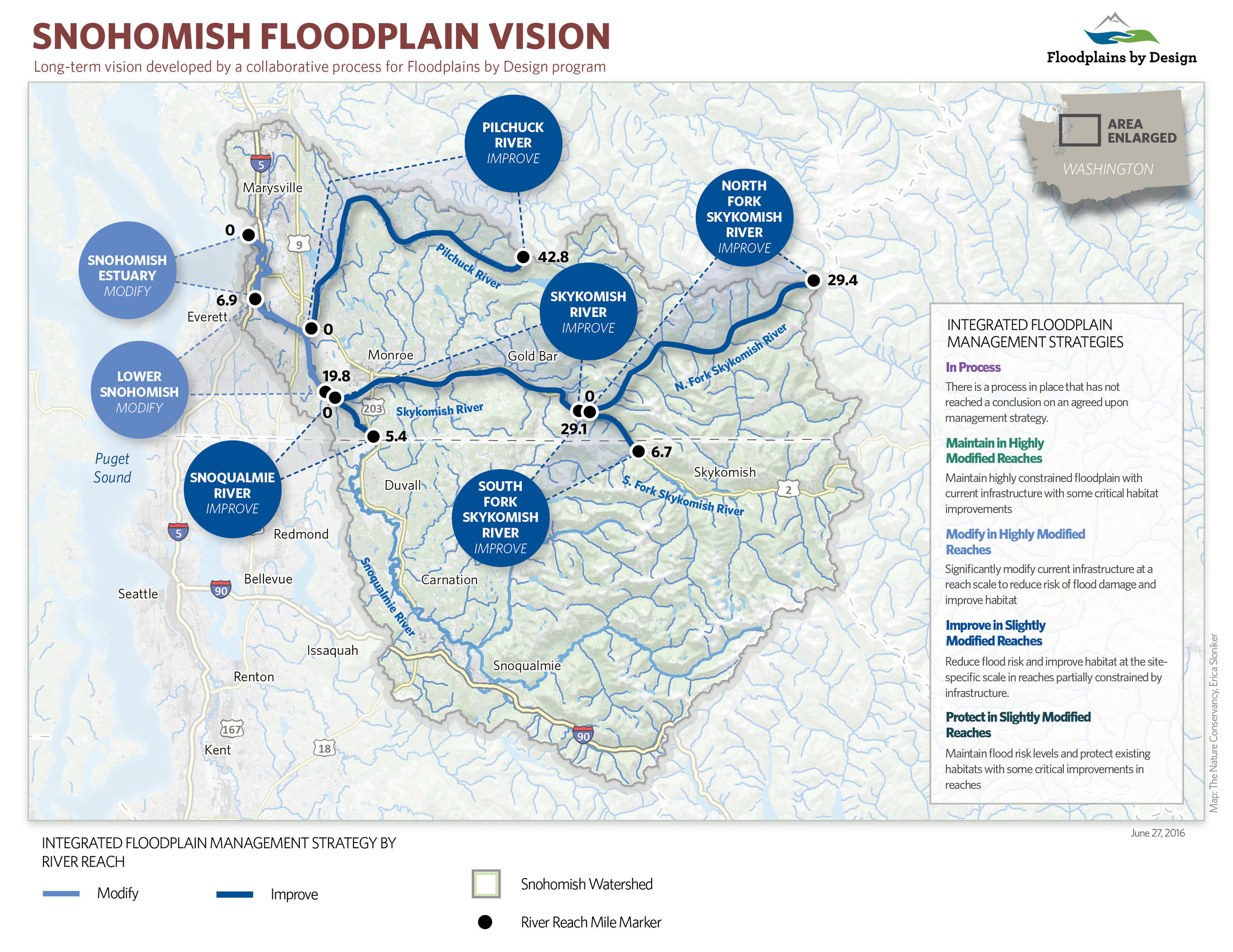

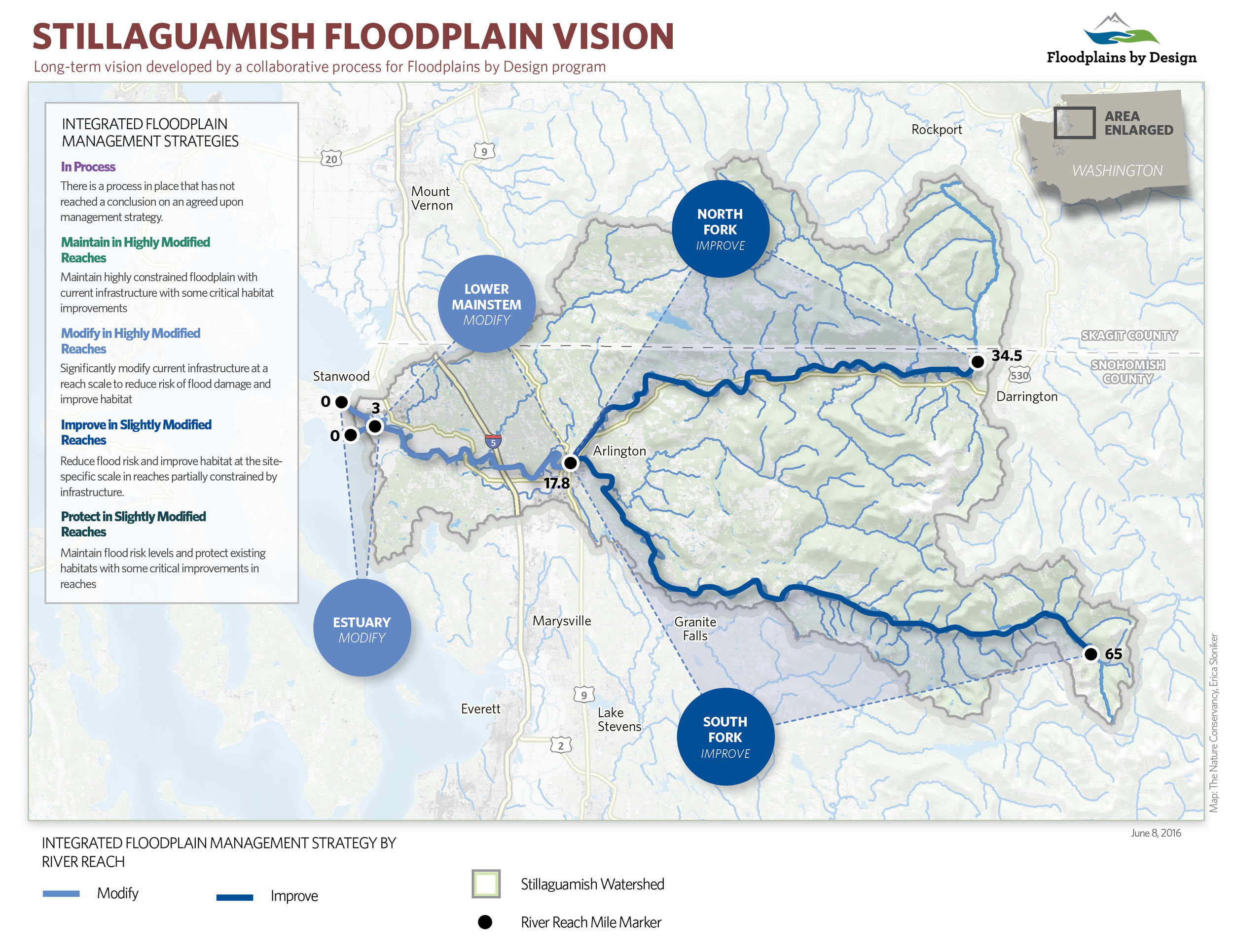

Maps by: Erica Simek Sloniker

Rivers and their associated floodplains are amongst the more productive ecosystems on the planet in terms of the goods and services they provide people: fisheries, rich alluvial soils, places for floodwaters to spread out and slow down, and that thing upon which all life and all economies depend – fresh WATER. Unfortunately management responsibilities and activities are parsed out through myriad competing and siloed programs and the result is less than stellar. Flood damages are on a troubling upward trend even as we look forward to a future of more severe storms. Salmon runs have declined precipitously. Water pollution persists.

The Floodplains by Design effort is looking to reverse these troubling trends by institutionalizing an integrated approach to river management – one in which interest groups work collaboratively to better understand how these systems work and to unleash the power of collective action to manage them in ways that increase health and resilience of both communities and nature. The first step in this process is for communities to develop a new, integrated vision of what they want to achieve and the actions they need to take to achieve those goals – watershed by watershed. Leaders in the majority of Puget Sound’s largest watersheds have begun this process. The results are a snapshot of current aspirations for river management in the region and provide a sense of the scale of potential on-the-ground actions.

It is clear that local leaders and partners in many watersheds have significant aspirations for improving the conditions of their floodplains for people and nature. There is an interest to significantly improve reaches of major rivers in over 40 percent of the 800 miles of floodplain in Puget Sound as well as protect the areas that are currently functioning naturally. While more work is needed for communities to come to collective agreement on their priorities in other river corridors, there is a process in place to create a unifying, broadly-supported vision and action plan to transform their floodplains. Erica Simek Sloniker, Cartographer and Visual Communications Specialist for The Nature Conservancy, has produced a map series to accompany these watershed visions.

Thinning for Resiliency

Written & Photographed by Zoe van Duivenbode, Marketing Intern

I recently drove to one of our central cascade properties to meet with field forester, Brian Mize, to learn more about how we plan to manage and restore our forests. Prior to my visit, I was unfamiliar with logging as a tool for restoration and was eager to find out how removing certain stands of trees can actually benefit the forest by improving health, increasing fire resiliency and creating habitat for wildlife.

Over the last decade, fire suppression has been a high priority among land managers and owners in hopes to protect property and habitat. However, this push away from fire has slowly changed the landscape of our native forests, allowing for certain species to thrive where they typically would not and creating denser tree stands. This shift creates a problem for land managers and nearby communities because it increases the risk and severity of forest fires. Certain trees, like grand fir, are more vulnerable to forest fires and have become more common among tree stands in central cascade forests. Also, forests with high density stands forces trees to compete with each other for resources, increases the amount fuels for fires and reduces habitat suitability for wildlife.

The Nature Conservancy plans to apply restoration thinning techniques on select units of our central cascade properties to create a more historic and variable forest structure which will benefit communities, wildlife and nature. On July 9th, TNC is inviting the public to one of our central cascade properties to see our restoration first hand and learn more about the benefits of restoration thinning. Our field forester will share more about the science behind thinning, and will answer any questions about our restoration work.

Join us for Forestry Day and see our work!

Learn more about our Central Cascade Preserves

From the Field: Log jams at Ellsworth Creek

Video by David Ryan, Field Forester

Check out this video from the field showcasing how we construct log jams!

In the late 1970's and early 1980's, many northwest streams were completely logged - log jams restore the woody debris salmon need. This project helps reach our restoration goals for the nearly 10,000 acres of Olympic land and water we protect.