Officials from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Congress and local leaders spent the day at TNC’s Port Susan Bay Preserve and Stillagumaish Tribe’s zis a ba II site to see ongoing restoration and discuss the impact federal infrastructure investments are having locally in Washington.

Leque Island: 250 acres open to the tide, create a place for young salmon and crab

We're Taking Puget Sound's Stories to the Nation

Eelgrass, home for sea life, is holding its own in Puget Sound

Some news from the bottom of Puget Sound: The total area of eelgrass beds hasn't changed much in the past 40 years. When other habitat areas have declined, this is encouraging — especially considering the number of aquatic species that use eelgrass beds, from young salmon to crabs. Eelgrass beds are common in tidal zones and along shorelines.

“Eelgrass meadows can grow so thick that when you’re swimming through them, you can’t see anything else,” said co-author Tessa Francis, of the Puget Sound Institute at UW Tacoma, in an interview with The Seattle Times. Watch the video for a diver's-eye view of eelgrass beds off the south coast of Whidbey Island. (Video courtesy of Ole Shelton, NOAA).

The report, co-authored by our lead scientist Phil Levin, was published in the Journal of Ecology. Another promising find was that significant changes in eelgrass beds occurred on a very small scale — meaning local action may likely lead to positive results.

"Our human population has exploded, we have all kinds of increasing impacts on Puget Sound, and yet eelgrass is resilient," said Phil. "It gives us hope about the ability to restore eelgrass. It tells us that what we do at the neighborhood scale matters, and we can have a positive impact."

Phil added that one of the largest increases in eelgrass is near our Port Susan Bay Estuary Restoration Project. The Stillaguamish River spills into the bay, mixing freshwater and saltwater to create extensive estuarine marshes that produce a vast quantity of decaying organic matter, helping the offshore habitat.

The data that have been collected and used in this analysis are incomplete and several of the findings beg further research — such as how adjacent areas have very different trends and nearby population density doesn't seem to have a strong correlation with negative impacts on eelgrass beds.

Read The Seattle Times' Article

About the Analysis

Jared Rivera: A Doris Duke Conservation Scholar

Written & Photographed by Kat Morgan, Puget Sound Community Partnerships Manager

On a chilly morning in the North Sound, 20 semi-sleep deprived undergraduates from across the country (there were some fireworks and late nights at their campsite the previous night) stood in our Mount Vernon office parking lot learning about who The Nature Conservancy is, and our work in Washington, particularly Puget Sound. These were the 2016 cohort of Doris Duke Conservation Scholars, a program sponsored by the University of Washington. This two year program is designed to help foster and ultimately increase diversity in the conservation workforce. These were the first-year students – freshmen and sophomores - participating in this 8-week field program in Washington. They visited conservation projects and professionals around Puget Sound, learned about current conservation needs and issues, and about the people doing this work. We toured our Mount Vernon office to give them a sense of what it might be like to work for The Nature Conservancy, and then headed to one of our flagship project sites – Port Susan Bay. Most students knew the Conservancy purchased and conserved lands. Only one knew that we actively managed those lands, or that we supported and implemented large-scale, landscape changing projects beyond our own ownership.

After hearing about the needs for restoring floodplain systems across Puget Sound, they had lots of questions about how you work with communities to do this work. What kinds of outreach were required, and how did you go about it? We talked about how each community has different needs, and you approach each community differently depending on the circumstances and people involved. They nodded their heads when we talked about the similarities – in each community, you ask questions and listen. You listen a lot - to understand what is needed, what is important to the people who live in that place, and you work together to find space for all those needs in a project.

We toured the Port Susan Bay restoration project site at low tide, when all the restored tidal channels and estuarine marsh were visible and visited the flood return structure, installed to address local flood issues as part of the project. Migrating shorebirds moved around the shallow pools left by the tide. The students marveled at the remoteness of the site, even though houses are visible all around, and the subtle energy, where at a distance everything appears very still, but when you get closer, you see song and shore birds flitting round the marsh, rushes moving in the breeze, and raptors on the wing looking for lunch.

As we wrapped up the tour, we turned the tables and I asked questions of this group of future conservation professionals. Jared Rivera is one of the Doris Duke scholars. He studies environmental engineering at UCLA. As a Native American, Jared is very interested in the intersection of social justice and conservation, in making sure Native American communities are engaged in problem-solving and decision-making around natural resources. Jared appreciates the interdisciplinary teams the Conservancy puts together to tackle conservation problems, and one day, when he finishes his environmental engineering degree, is interested in a seat at the table.

PROFILE

Name: Jared Rivera

Hometown: Murrieta, Southern California. Going to college at UCLA.

Murrieta is located in the center of the Los Angeles San Diego mega region of 20 Million people. After interstate 15 was built in the 1980’s, suburban developments started being constructed. Today, Murrieta is known as a commuter town and the largest employer is the school. I know this area though. I have family on Camano Island. It’s really interesting to hear about your projects here.

Childhood Dream/what did you want to be when you grow up?:

Until I was 17, I wanted to join the Marines. Then my ideas changed. I had an AP bio teacher who taught us about ecology and took us on field trips to the Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies. I was fascinated by a project they were working on of sustainable algae fields for biomass production. I applied for a student study program at the Wrigley Institute and was accepted.

What about our work do you find most inspiring? What is most surprising?

The Levees at the Port Susan Project. The fact your conservation organization isn’t afraid to make changes to the environment, and to build infrastructure if it will help you accomplish your goals. Humans have already meddled with nature to mess it up. The only way to fix it is to keep meddling.

What would you most like to see The Nature Conservancy work on that you didn’t hear about today?

I would like to see The Nature Conservancy become more involved in social justice issues. Particularly as a Native American, I would like to see more indigenous communities included in the problem-solving and decisions around our natural resources.

What would make you want to work for us?

I am really excited about the interdisciplinary approach you described bringing experts from all different fields together to problem-solve, to have a seat at the table, particularly involving social justice issues.

Rebuilding an Estuary, Designed by Nature

Written by Beth Geiger, Northwest Writer

Graphics by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

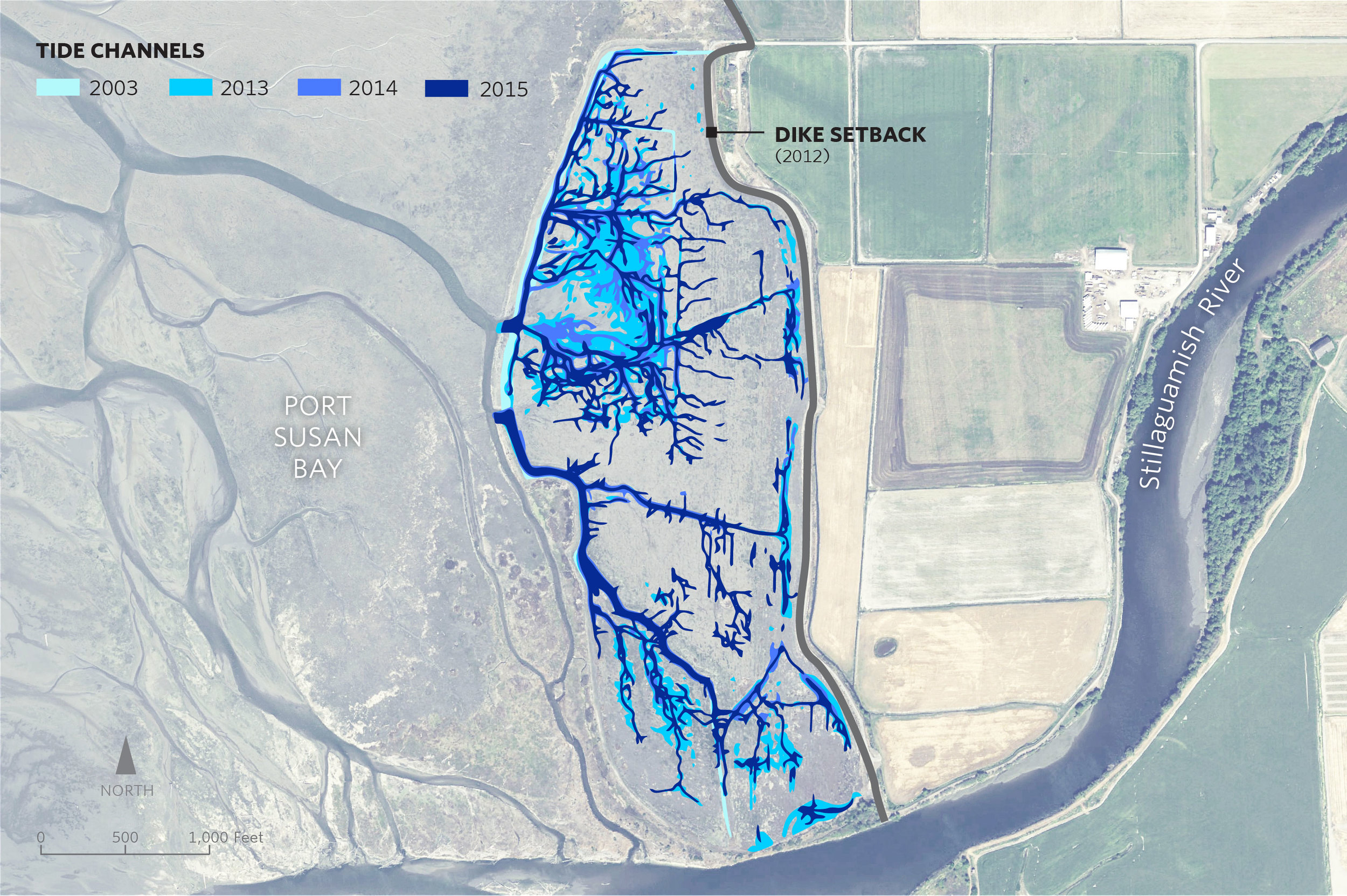

A dramatic change has taken place in a marsh in Port Susan Bay, near Stanwood, Washington. In just three years the total length of tidal channels naturally increased tenfold, from 2,300 to 23,000 meters.

Tidal channels are key to a well-functioning estuarine ecosystem. Channels increase habitat diversity, which in turn increases species diversity. Juvenile salmon use the channels, dabbling ducks use them, and invertebrates that provide food for other species use them.

Scientists like Roger Fuller, an ecosystems ecologist at Western Washington University, are chronicling the new tidal channels, along with other changes here. Fuller says the development of so many new channels is “a big surprise.”

Marsh Revival

The new channels started forming in 2012, after The Nature Conservancy removed 7,000 feet of dike that had separated the 150-acre marsh from the rest of Port Susan Bay since the 1950s. The dike removed had over time diverted Hatt Slough, the Stillaguamish River’s biggest distributary channel, south where it spills into Port Susan Bay. That dike had also cut the marsh off from its main source of fresh water and sediment.

With marsh, river, and Puget Sound connected again, natural processes took over. Critical estuary habitat quickly began to be rebuilt. A natural revival was underway.

The channels are a big part of this revival. “Channels build connections, creating the intimate links that tie the marsh, tide and river together,” Fuller explains. “They serve as the trade routes of the estuary, funneling water, sediment, fish, and the organic matter that fuels the entire estuarine food web back and forth between marsh and tidal flat.”

Sound Science

Supported by the Conservancy, Fuller and other scientists including Greg Hood with the Skagit River System Cooperative, and Eric Grossman, Christopher A. Curran and Isa Woo from the United States Geological Survey have been studying the channels and other ways that this estuary is recovering.

The researchers analyze before and after data, and compare the restoration area to a nearby reference marsh which has never been diked. They measure suspended sediment, water temperature, salinity, current, as well as topographic and ecological changes.

New tidal channels aren’t the only “before and after” they’ve seen. When the dikes were in place, the area inside them had been starved of its natural influx of sediment from the Stillaguamish River. The estuary had subsided until it was a meter lower than the surrounding tidelands in some places. It functioned more like a pond than a dynamic estuary. For example, there was no access or protected estuarine habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon transitioning from the Stillaguamish River into Puget Sound.

With the dike removed scientists have recorded a measurable rise in the height of the marsh. During those years the sediment delivered to PSB was unusually high in part due to the March 2014 Oso landslide. However, the data suggest that even if the marsh gets half as much sediment in future years, it may still rise fast enough to keep up with the rising sea level, estimated to be an average of about 24 inches by 2100.

Lessons from Nature

Fuller says that being surprised by nature here isn’t all that unexpected. “The one thing I knew before the restoration was that I would be surprised by the changes triggered by the restoration,” he says. “There's been so little research on restoration in northwest estuaries that I knew it would be really interesting to watch it unfold.”

The restoration project is part of the Port Susan Bay Preserve, which includes 4,122 acres of estuary that the Conservancy acquired in 2001. The science being conducted here reaches much further than the Preserve itself. Along with learning new lessons, we are applying scientific concepts and models honed under this and other Conservancy projects such as Fisher Slough.

Together, these projects demonstrate that carefully planned restoration can have complementary, not conflicting, benefits for people, salmon, farms, and wildlife. The Conservancy-led Floodplains by Design provides the partnerships and funding that ensure these lessons can extend to restoration projects all over Puget Sound.

As a result of diligent science and critical partnerships like this, we are learning how to make Puget Sound more resilient as climate changes, and sea level rises.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK IN PUGET SOUND

LEARN HOW CLIMATE CHANGE WILL AFFECT THE REGION AND WHAT WE'RE DOING TO ADAPT

Sights and Sounds: Snow Goose Festival

Video courtesy Scott Wild, Northwest Videographer

Sights and sounds of Port Susan Snow Goose & Birding Fest at our Port Susan Bay Preserve!

Learn more about our work in Puget Sound

Livingston Bay: Remodeled by Nature

Written by Joelene Boyd Puget Sound Stewardship Coordinator /Interim Stewardship Director

Maps by Erica Simek Sloniker, GIS & Visual Communications

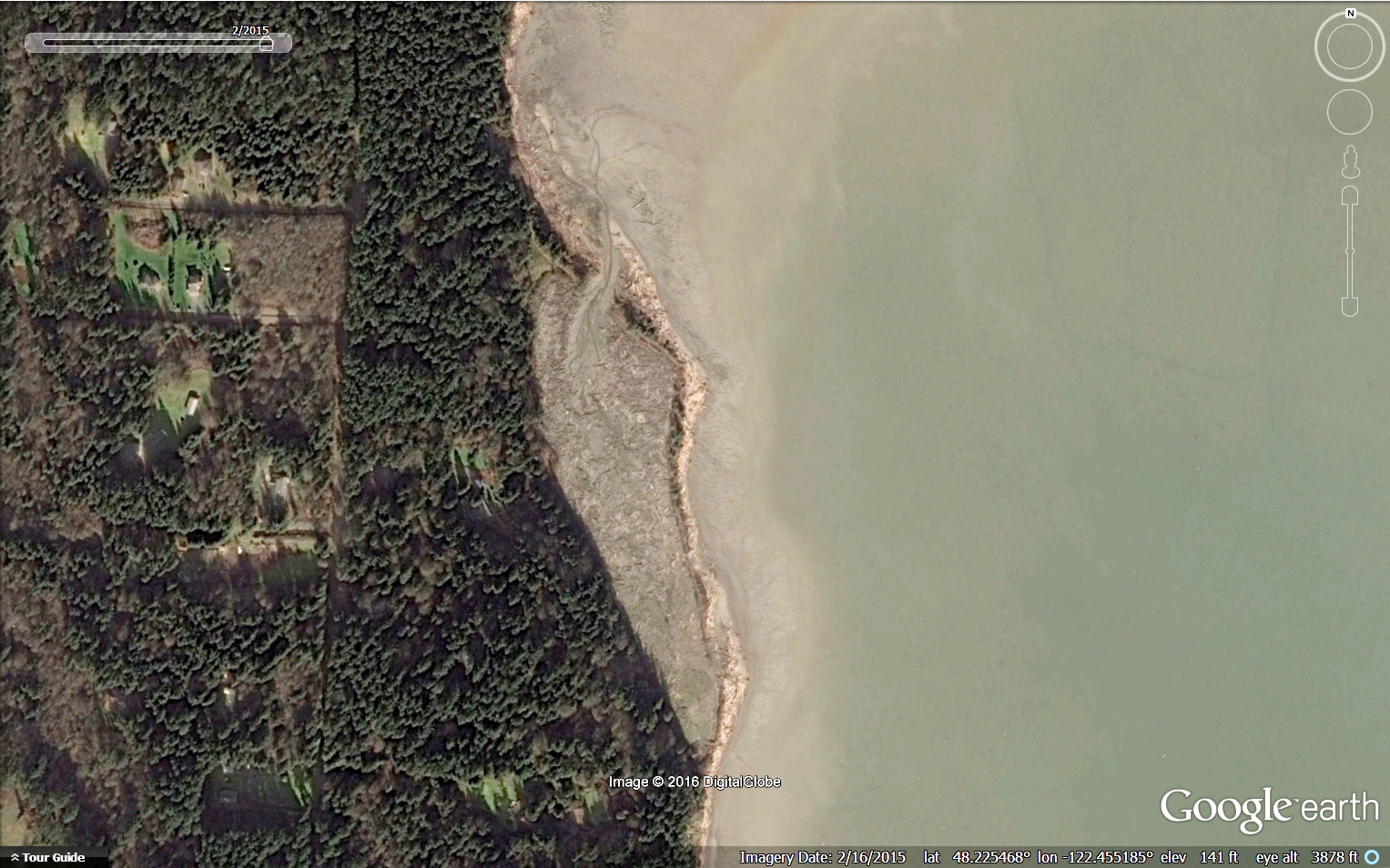

Three years later the change is remarkable! Wood has moved out of the pocket estuary, the channel network is expanding and a natural sand spit is forming.

In 2012 The Nature Conservancy set work to restore a 10 acre pocket estuary in Livingston Bay. In order to do this we hired contractors to repair the breach at the southern end of the pocket estuary, breach the dike on the north end and excavate a “starter” channel so that tidal exchange would return. The desire was for wood to be carried out of the site by wind and tides and a channel would grow. The major goals of the project were to restore tidal influence to the pocket estuary, improve access for juvenile salmonids and other fish and restore salt marsh habitat.

From aerial images we see that this is exactly what’s happened - wood is moving out of the site through this starter channel allowing a network of channels and salmon habitat to develop. Additionally the natural sand spit is continuing to extend. It is impressive to see nature’s forces working to restore this pocket estuary with a little helping hand.

A pocket estuary is a type of nearshore habitat that is used to describe an estuary that is protected from waves, wind and other forces. Pocket estuaries in Puget Sound provide critical rearing habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon and other fishes that depend on these partially enclosed estuaries to eat, grow and seek refuge from predators. Researchers estimate that in the Whidbey Basin approximately 80% of the pocket estuaries have been lost.

Historically the Livingston Bay pocket estuary had been diked in the early 20th century to allow for grazing. However, sometime in the 1980s a storm had breached the southern end of the dike causing the area to fill up with wood from strong winter windstorms and high tides. After purchasing the property the Conservancy set to work on designing and carrying out a restoration project to restore the daily tides and function of the pocket estuary necessary to provide juvenile Chinook habitat which was identified as a limiting factor for Chinook salmon survival (Beamer 2003).

Learn More About Our Work in Puget Sound

Fir Island: Collaborative Restoration for Salmon, Wildlife and People

Big habitat gains were celebrated at the June 30th groundbreaking for a restoration project at the Fir Island Farms Unit of the Skagit Wildlife Area.

Written by Cailin Mackenzie, GLOBE Intern

Photographs by Jason Wettstein, Washingon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife

“This kind of project takes real collaboration,” said Bob Everett, from Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), and this collaboration will provide exponential benefits to the five native salmon species that call Skagit delta home.

This $16.4 million project, led by WDFW, will restore 131 acres of tidal marsh habitat and set back 5800 feet of existing dike, moving about 10,000 truckloads of dirt along the way. The restoration will provide enduring benefit not only for salmon recovery, but also for agriculture and communities.

Jessie Israel, The Nature Conservancy’s Director of Puget Sound Conservation pictured fourth from the right, lauds the project team’s partnership on large-scale restoration with lasting environmental impact. “That’s the only way we’re really going to get things done.”

The large scale of this project would not have been possible without broad and synergetic collaboration. The Nature Conservancy worked with WDFW, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Puget Sound Partnership, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Estuary and Salmon Restoration Program, along with other invaluable partners, to simultaneously restore habitat for migrating juvenile Chinook, protect against saltwater intrusion to farmland, and ensure public access for bird watching.

The Fir Island project closely aligns with The Nature Conservancy’s conservation strategies – we are committed to fruitful teamwork that secures victories for humans, animals, and nature alike.