Our forester Ryan Haugo says he can't "think of a more interesting ecosystem to study" than the Washington Central Cascades forests. Learn more about Ryan and the work he's doing for forest health and resiliency

Schooled on forest-health management

Writing and photo by Dr. Dave Shaw, Oregon State University

Ryan Haugo, a Nature Conservancy senior forest ecologist, hosted our graduate field forest-health class in the Manastash-Taneum Resilient Landscapes Project area in September. It was an epic visit that completely blew our minds.

Beginning with a stunning view of the Washington Cascades, Ryan introduced us to the Tapash Sustainable Forest Collaborative, which is implementing a scientifically based ecosystem-management plan for a complex terrain with mixed owners and ownership history. The landscape is rugged, showing recent fire impacts and is comprised of mixed conifer forests, which vary depending on elevation, aspect and soils.

The effort to use active management, such as forest thinning, planting and prescribed fire, to advance ecological integrity and biodiversity, is a classic example of forest-health management.

This is the application of knowledge gained by a group of interacting scientists and managers, led by the U.S. Forest Service's Pacific Research Station, The Nature Conservancy and University of Washington scientists. It can be considered a test of current theories on how best to manage Eastside Cascades forests for the benefit of everyone.

Read more about the Central Cascades forest

The 'cutting edge' of forestry practices

Writing and photos by Ryan Haugo, forest ecologist

On a misty December morning, an esteemed group of forest ecologists from across the Pacific Northwest met with our staff along the shores of Willapa Bay to talk science and restoration. This group had driven through dark morning hours in order to spend the day tromping around the forest and building and strengthening science partnerships, while gaining a first-hand experience with The Conservancy’s “Ellsworth experiment.”

The Ellsworth Preserve is best known for protecting some of the largest remaining stands of coastal old-growth rainforest in southwest Washington. Towering forests of Western red cedar, Sitka spruce, western hemlock and Douglas fir support a number of endangered and threatened species as well as coastal cutthroat trout, chum and coho salmon. However, the preserve doesn’t just protect old-growth forest. In fact, the preserve is predominately young, dense forests that for many decades were heavily harvested for timber. In 2006, we launched the audacious goal of conserving and restoring the ecological integrity of these former industrial forest lands.

At the time, moving from the protection of small preserves to entire watersheds and diving headlong into active forest management was a huge step for The Conservancy. The best available science suggested that forest thinning (logging!) and repair or decommissioning of forest roads would be important tools to aid recovery of coastal watersheds and restore old-growth habitats. However, across the Pacific Northwest coast, there were few examples of full-bore ecological restoration at such a scale. Our Ellsworth experiment applied a rigorous design and an extensive monitoring network to test and evaluate the best approach. Before the first forest treatments began, we conducted detailed measurements of forest structure and vegetation, birds and amphibians and stream habitats to establish a baseline.

Often we describe science as “cutting edge.” This might make it seem that data, the fundamental building block of science, have a limited lifespan and easily spoil if left too long on the counter. Sometimes this is true. But when science is done well, using experiments designed for the long haul, data are more like fine wines that get better with age. Do our original 10-year-old measurements from Ellsworth still have value? Absolutely. Ecosystems change slowly, and our pre-treatment data are just now ready to pair with updated findings on the state of the preserve today.

This will allow us to start answering the fundamental questions of the Ellsworth experiment. But we need to identify creative collaborations and funding opportunities to ensure a return on our investments in healthy forests (consider donating to help continue this work). Through outreach and an open invitation to the science and conservation communities, we hope to foster an extended shelf life for our data. The insights yet to be revealed have the potential to inform future forest restoration within and beyond Ellsworth.

As we concluded the Ellsworth science tour in the early December twilight, our boots were heavy with mud but our spirits were buoyant and enthusiasm was high. The pre-treatment data provide a tremendous foundation. New technologies are emerging to aid in our efforts and exciting new partnerships are on the horizon. The second decade of science at Ellsworth is looking very promising.

Read more about the Ellsworth experiment

A New Way, A New Forest

Written by Robin Stanton, Media Relations Manager

Photographed by Hannah Letinich, Volunteer Photographer

Some 25 foresters from a variety of agencies hiked up into the sun-filled forest of the LT Murray Wildlife Area on a May morning to practice a new way of evaluating tree stands and selecting trees for ecological restoration thinning.

The workshop, led by University of Washington research scientist Derek Churchhill who developed the method, was organized by our own senior forest ecologist Ryan Haugo.

LISTEN TO THE DAY FROM NORTHWEST PUBLIC RADIO

It brought together foresters from the U.S. Forest Service, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Washington State Parks, Department o fNatural Resources, and The Nature Conservancy to learn this new way of ecological restoration. The method, called ICO, for Individuals, Clumps and Openings, is designed with the goal of creating a mosaic pattern in the forest to make it more like historic conditions.

This all part of the preparation for a 100,000-acre restoration project in the region to be carried out by the Tapash Sustainable Forests Collaborative, of which the Conservancy is a partner.

Learn More About Our Work in Forests

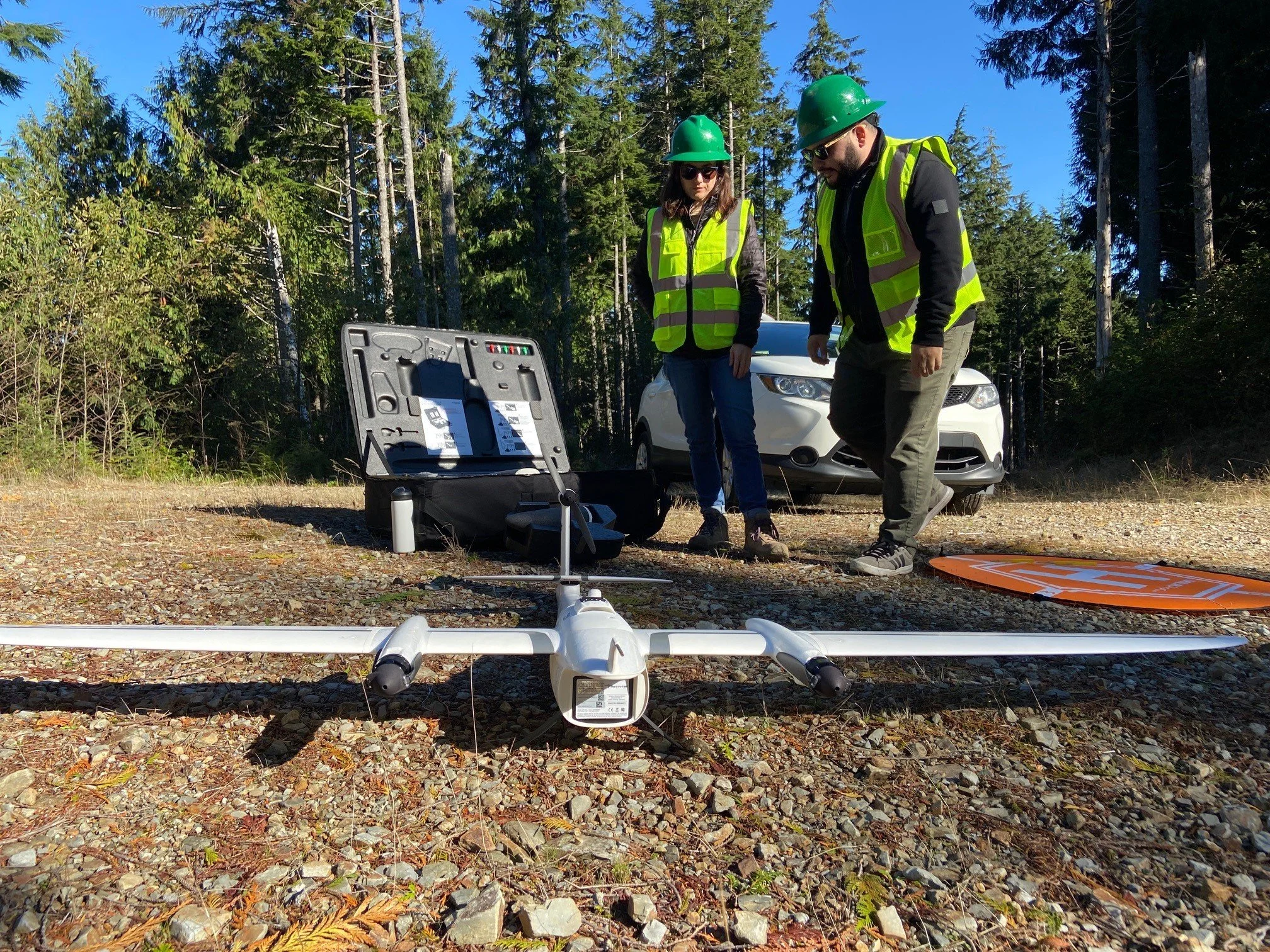

SOARING ABOVE THE CENTRAL CASCADES

Volunteers recently took to the skies to capture this amazing footage of our recent 48,000 acre forestland purchase in the Central Cascades.

Footage by Whitney Hassett / Geodesy