By Owen L. Oliver, Freelance Writer (Quinault / Isleta Pueblo)

The Nature Conservancy’s Ellsworth Creek Preserve, which occupies the ancestral homelands of the Willapa and Lower Chinook people has and continues to be a host of hundreds of teachers. Plants and animals are landscape informers. At Ellsworth, we learn the cyclical teachings of salmon. We understand the resiliency of old-growth conifers and the sensitivity of the marbled murrelets who nest in them. We can even repair some wounds.

North America Beaver, Castor canadensis, © iStockphoto.com/James M. Kruger

Beavers were once hunted to near extinction when the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) occupied numerous forts around the Columbia River in the 17th century. The Columbia River stretches around 1,243 miles from the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia to the Pacific Ocean. As the HBC moved west, it continued to premediate the domination of the fur trade over living creatures. Beaver, who was targeted and made into hats, is a keystone species. Once beaver populations began to be decimated, wounds were becoming more severe.

Beaver’s role as a keystone species is the engineer of the land. Within minutes, they begin to alter the land. The gnawing on soft woods provides them with a special trifecta of benefits, food and dental care—and leads to the felling of a tree. Within hours, they create a foundation for their family lodge. Damming up a stream or river with logs and saturating gaps with mud. As their construction continues, a body of water pools. Within days, the water is filtered through the beavers’ home decreasing the turbidity downstream. Water that has pooled becomes slower, cooler and deeper. It is now a more advantageous nursery for fish, amphibians and birds. Beaver changed the landscape, and every animal benefits from it.

After The Nature Conservancy conserved Ellsworth Creek Preserve in the early 2000s, scars still lie on the land today from the near-century history of logging. The effects of clear-cutting affect the engineer of the forest. The absence of softwoods like willow, cottonwood and red osier dogwood limits beavers’ return and the craftsmanship of their lodges.

An aerial photo of TNC’s Ellsworth Creek Preserve from 10 years ago, showing the impacts on the landscape from a century of logging. © Chris Crisman

Washington Coast Community Relations Manager Garrett Dalan plants a cedar and Sitka spruce sapling alongside Ellsworth Creek, March 2023. © Nikolaj Lasbo / TNC

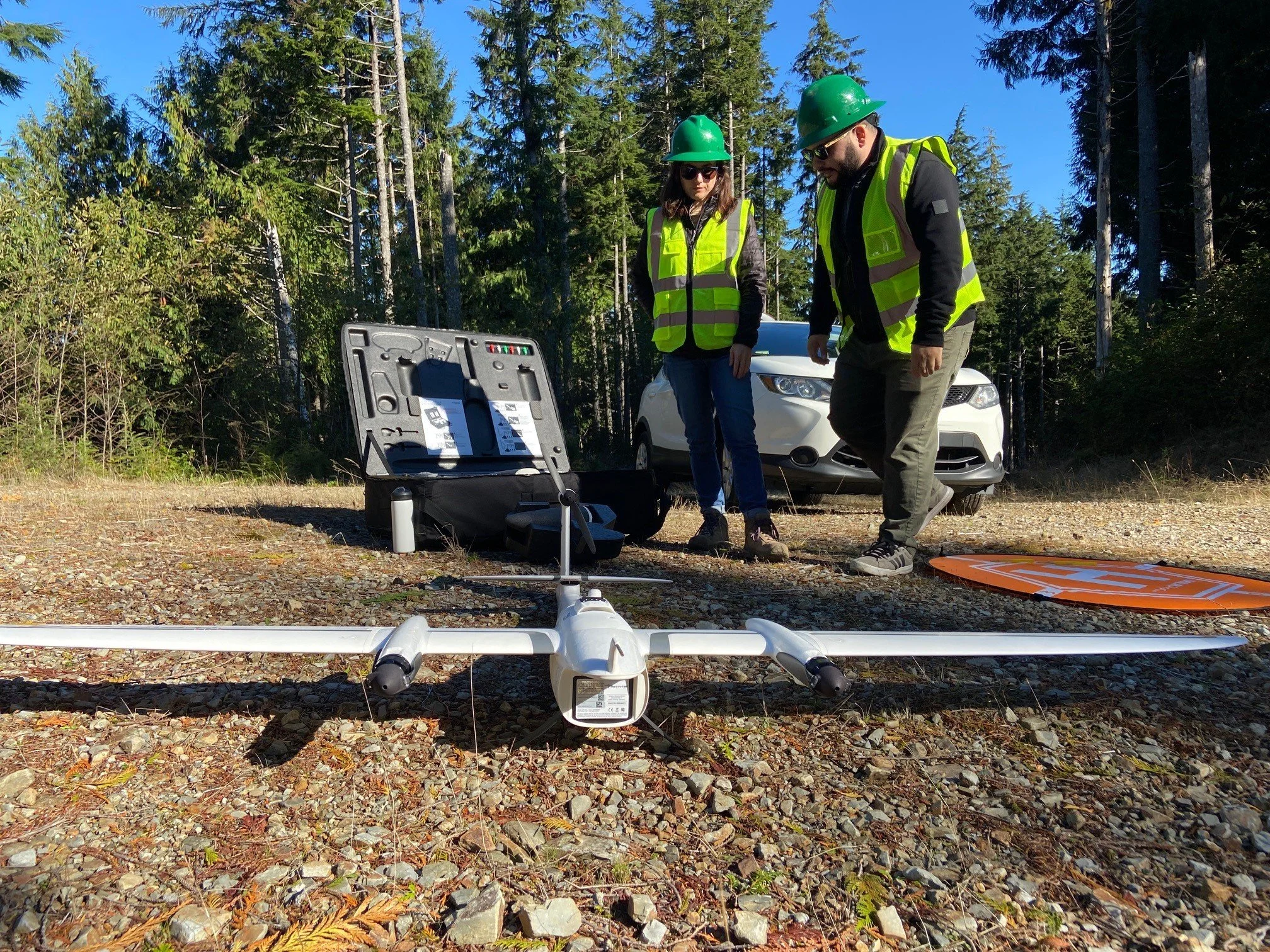

Last March, 13 Nature Conservancy staff, many for the first time, were introduced to Ellsworth Creek Preserve. Here, staff members continued the efforts of revitalizing healthy riparian areas along the creek to improve chum and coho salmon nurseries. The projects on this cool and wet spring day on the Washington Coast focused on planting a healthy food buffet for the beaver population.

Quena Batres, volunteer and community engagement manager for The Nature Conservancy’s Washington chapter, helped organize the outing. She saw the activity as strengthening the forest as well as staff camaraderie. Batres explained, “It’s important to build the memory of working on the land and relate it to our work at The Nature Conservancy.” She noted that staff are encouraged to continue to take the opportunities to immerse themselves in TNC’s preserves to ground themselves in the work they do.

Kyle Smith, the Washington chapter’s forest manager, has been connected with the Ellsworth Creek Preserve for 15 years. Each time he visits he learns something new about the area. While guiding this adventure, he kept thinking about the intuition of beaver and the immense ripple effect beavers have on hydrology, how water moves in relationship with the land, within Ellsworth Creek, which flows out to Willapa Bay. To continue the healthy outcomes of beavers influencing the hydrology, they need to have access to suitable trees. Where tall old-growth giants are revered at Ellsworth, it’s essential to also have softer and smaller trees that provide the food sources and habitat that beavers need.

Signs of recent activity and beaver teethmarks on a young willow alongside Ellsworth Creek, March 2023. © Nikolaj Lasbo / TNC

““Staff trekked through the woods, maneuvered up and over large, downed trees, and waded through the creek carrying bags full of conifer saplings, cottonwood and willows… while getting our hands dirty and for some of us, our feet wet!””

In total, the group planted 1,620 plants and trees along Ellsworth Creek across the two-day trip. Quena and Kyle plan to continue this planting next March, with the goals of ensuring healthy salmon habitats, combating erosion, and assisting with beaver repopulation. Following up on the project last March, The Nature Conservancy was already able to see fresh beaver clippings and a new beaver dam constructed on Ellsworth Creek!

“Staff trekked through the woods, maneuvered up and over large, downed trees, and waded through the creek carrying bags full of conifer saplings, cottonwood and willows.” – Quena Batres. Photo © Nikolaj Lasbo / TNC

In North America, beavers once amassed populations of hundreds of millions before European contact and before they were driven to near extinction through trapping—now they are slowly regenerating to around 15 million today. Their important actions and lessons on relationality help fuel the understanding of a thriving forest. Chinook People, the original inhabitants and stewards of Ellsworth Creek and Willapa Bay, have cultivated this beaver knowledge and cemented it into their language (Chinuk Wawa). We can learn from these knowledge systems to know that ina (beaver) has a favorite tree called ina-stik (willow).

Owen L. Oliver (Quinault / Isleta Pueblo) comes from the people of the Lower Columbia River, Salish Sea, and Southwest Pueblos. He grew up in Ketchikan, Alaska and Seattle where in 2021 he graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in American Indian Studies and Political Science. His work is concentrated in Indigenous education and cultural representation, a path that he's learned from his connection to Pacific Northwest Tribal Canoe Journeys. As a freelance writer for The Nature Conservancy, Owen is helping bridge conservation and Indigenous perspectives and is bringing his own values and viewpoints to our writing and storytelling.