Nature signals spring. In Texas it is blue bonnets, in New England, robins, and for the Emerald Edge of Alaska, British Columbia and Washington, it is the return of herring.

Written & Photographed by Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

For millennia, Pacific herring have been harbingers of spring. Historically, they returned in great numbers to spawn on kelp, seagrass and gravel throughout the Pacific Northwest. Their arrival was quickly followed by horde of sea lions, humpback whales, seabirds, and eagles all gorging on this plentiful prey. And in their wake, killer whales arrived to eat the sea lions and whales. With the arrival of herring, the waters of the Emerald Edge erupt with life.

And for the indigenous people of the Emerald Edge, herring eggs bring the first pulse of fresh food of the season. For the Haida, Tlingit and many other peoples, herring eggs are perhaps second only to salmon as the most culturally revered food. The Haida gather herring roe on kelp, while Tlingit set hemlock branches in the water and collect the thick layers of herring eggs that coat the limbs. Those who gather the delicacy will eat it themselves, share with family and friends locally and in distant communities, or trade for other products. Every feast and celebration will be accompanied by mounds of bright herring eggs that connect people to each other, their past and to the ocean.

Herring also signal the opening of the fishing season for commercial fishers. Many fishers who latter will focus on the lucrative salmon fishery, start their year with herring. In Southeast Alaska, over the last decade these boats scooped up an average of about 13,000 tons, annually. The unspawned roe is coveted in Japan, and in recent decades this has become a lucrative market. Both the income generated by the herring and the opportunity to break in new crew at the beginning of the season are critically important for many fisherman.

Herring are thus central for nature, for culture and for the economy of coastal communities. However, historic overfishing, pollution, coastal development and climate variability have resulted in many declining stocks of herring. In some places, the number of fish is so low that fisheries have been closed for years. In recent times, then, herring has not only announced spring, but has also marked a time of conflict.

Last year, my colleagues from the Ocean Modeling Forum (OMF) and I brought together more than 125 First Nation and Tribal Elders, governmental officials, scientists and environmental NGOs and asked what were the critical science gaps for science management. As one of the directors of the OMF, my role is to connect diverse types of knowledge and bring it to bear on pressing ocean management issues. In the case of herring, we learned that the extensive traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often marginalized in management, and the cultural costs and benefits of herring are not adequately considered in decision making.

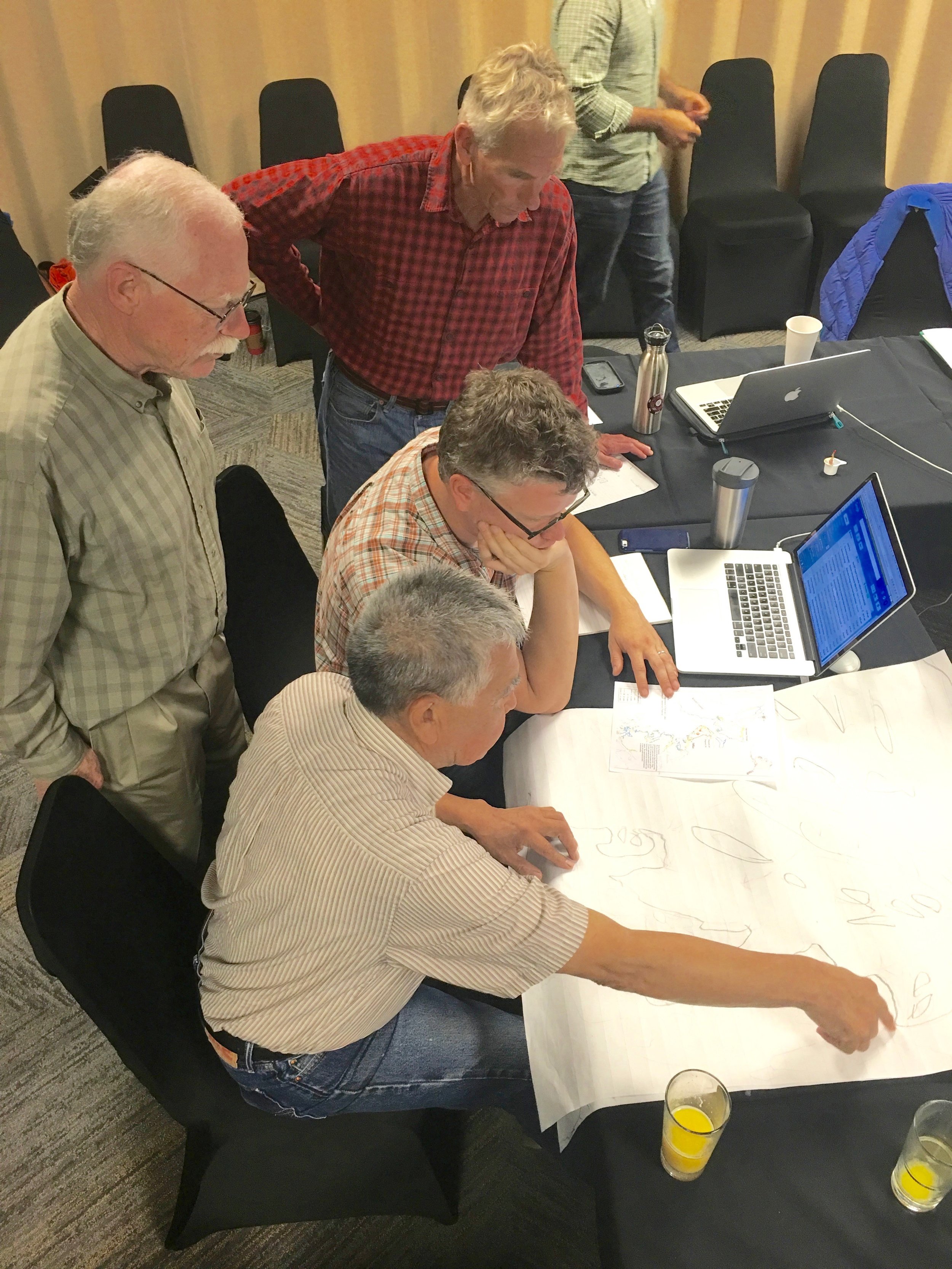

To fill these gaps the OMF created a working group of 18 social and natural scientists, traditional knowledge holders, commercial fishers, and resource managers to tackle this problem. I just returned from co-chairing the 3rd meeting of the OMF herring group (with Dr. Tessa Francis from the University of Washington Puget Sound Institute) which met in Sitka, Alaska. The group has made great strides in incorporating traditional knowledge into quantitative ecological models – the language of fisheries management. Working collaboratively across our professional silos, we have developed the means to formally examine management alternatives to determine their ecological, economic and cultural outcomes—the triple bottom line.

After the OMF meeting concluded, I had the privilege of visiting historic and current herring spawning grounds with Harvey Kitka – an elder of the Sitka tribe. Each cove and beach seemed to have a story of plenitude and demise. Harvey spoke about the time when herring were so abundant that they jumped from the water and the crack of their bodies hitting the ocean’s surface would echo across the Sound like hail. Those days are gone. Instead, Harvey pointed to islands were there was just a little spawning here and a little spot there. He spoke with sadness about the present, but was always optimistic about the future, and the work we are trying to do.

Solving difficult conservation problems, like herring conflicts along the Emerald Edge, will require new approaches and innovative thinking. My experiences working with a diverse group of people with vastly different perspectives on herring, suggest that given the chance people can rise to the occasion and tame these wicked problems.

Learn more about our work in the Emerald Edge