New research reveals the perspectives of fishing communities in Washington, Oregon, and California and connects it to data-driven science on climate risk, providing the strongest foundation for developing plans that ensure the resilience of fishing communities.

Climate Change and the Wellbeing of Coastal Communities

Fisheries Market Analysis - Request for Proposals

Studying Sustainable Seafood in Seattle

Complementary Angles on Sustainable Angling

The Crab Pots that Got Away

Do You Know Who Peeled Your Shrimp? Why Social Sustainability Matters

Live Expert Panel: Conservation for the Anthropocene Ocean

This 'Trash' Tastes Amazing!

It’s More than Counting Fish: Where Social Science Meets Sustainability

A Scientist's Adventure on the Hill

Written by Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

The gentle rocking of the train car subsides as it pulls into the station called “The Mall”. My fellow passengers, dressed in the uniform of The City, and wearing important frowns, look up in synchrony from their phones. We join the scurrying masses through subterranean tubes, eventually rising to the surface where we step on the stage of history. Sandwiched between the U.S. Capital and Lincoln Memorial, I can only smile, as I make my way along the National Mall to the business entrance of the Capital.

A very large man with a very large rifle greeted me and my colleagues as we made our way through security and into a conference room on the Senate side of the building. I’ve given briefings on the Hill before, but this was my first time as a Nature Conservancy rather than government (NOAA) employee. The reason for my smile is now clear to me—since I am no longer a representative of the executive branch, I am allowed to eat Congressional cookies!

The conference room was overflowing with 50 Senate and House staffers, all of whom focus on ocean issues. We were there to roll-out a new report from the Lenfest Fishery Ecosystem Task Force. The report, Building Effective Fishery Ecosystem Plans, provides guidance to fisheries managers on implementing ecosystem-based fisheries management—a holistic place-based approach that seeks to sustain fisheries by maintaining healthy, productive and resilient ecosystems. The Task Force, convened with support from the Lenfest Ocean Program, consisted of 14 preeminent fisheries scientists from around the U.S. and world. Timothy Essington, of the University of Washington and I led the task force.

Our report highlights that connections matter. Indeed, this is the unifying principle of ecosystem-based fisheries management. Ecological connections matter because fishing affects target species, predators, prey, competitors, bycatch species, and habitat. Economic connections matter because management affects fishermen, wholesalers, retailers, and recreational fishing guides. And social connections matter because fishing supports families, communities and cultures.

While many have noted the importance of ecological, economic and social connections for oceans and people, fisheries managers have had a difficult time bringing this principle into practice. We concluded that a structured process for establishing goals and translating them into action is critical for overcoming the barriers to including these important connections in fisheries management.

As the briefing concluded, staffers immediately started asking questions. They were nonpartisan. They poked, dissected and deconstructed the information we provided them. They looked for connections between existing or planned legislation and executive orders. They conjured their boss as they sought clarification. They were smart, engaged critical thinkers. Looking out at them, it struck me that they seemed so young-mostly in their late 20s-30s. Realizing that these young staffers are the engine that make our government work, gave me great hope.

After additional briefings at the White House Council for Environmental Quality and the National Marine Fisheries Service, we were exhausted but further encouraged by those who work for our environment. I walked across downtown DC as the indigo night sky warmed the edges of the austere city. I joined the herds of suited laborers, ties loosened, and migrated home. The work has just begun.

Here come the Chum!

Written and photographed by Dave Ryan, Field Forester

On Thursday, October 20th four hopeful adventurers wended their way down to Ellsworth “Beach”, that small, rocky shore at the terminus of our old growth trail. The hope was that the recent rains and some applied positive mental attitude could summon the Chum salmon to make their annual run up Ellsworth Creek that day. Alas, our intrepid adventurers found no salmon that day; although a walk in the forests of Ellsworth is never wasted.

On Friday, October 21st a sole wanderer ventured back to the beach and welcome to Ellsworth Creek Chum Run 2016! At some point in the intervening 24 hours, the salmon made their push several miles up Ellsworth Creek. It is always a powerful experience seeing a salmon run; whether in Alaska, The Bonneville Dam fish ladders, at Klickitat Falls, or anywhere else in the world. However, there is a solitude, a solace, and an intimacy to the Ellsworth Creek Chum run that is especially powerful to me. Perhaps it is due to, rather than in spite of, the small scale. It is a favorite time of year in what is one of my favorite places in the world.

View the photo slideshow above to see the impressive chum run!

Learn more about Preserves like Ellsworth

A Message from the Sea

"I need the sea because it teaches me…

I move in the university of waves…

It’s ceaseless wind, water and sand…

I became part of its pure movement."

(from Pablo Neruda's The Sea)

Written by Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

I first read Pablo Neruda’s poem The Sea as a graduate student while working on Appledore Island – a little island one mile long and one-half mile wide, ten miles off the coast of southern Maine. It was one of those perfect stormy, gray days that was amazing to watch, but much less fun to be out in a small boat doing research.

Looking out at the swell rolling in across the Atlantic, Naruda’s words were etched in my mind. Neruda captures so well a feeling of motion that anyone of us who spends time around the ocean experiences. The tides ebb and flow, waves slap ashore, and currents stream by. But its more than that – the sea’s animals are in motion too. Salmon that began their life hundreds of miles inland swim past us on their thousands-of-miles journey through the Pacific. Humpback whales, which we are seeing in the Pacific in ever-increasing numbers, can travel more than 13,000 miles in a year. And Steller sea lions make phenomenal dives to depths of up to 1,500 feet to feed, staying underwater for as long as 16 minutes.

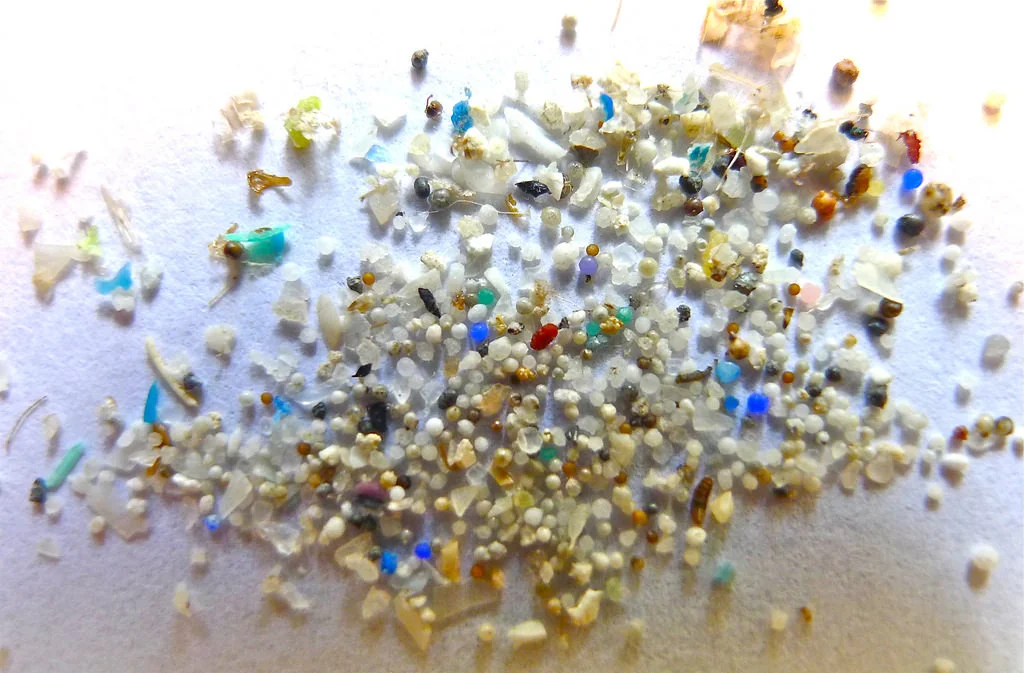

A few years ago a 14 foot pregnant six-gill shark washed up dead in South Puget Sound. My team from NOAA took samples from the animal and found that its tissues were laced with a form of the pesticide DDT that we know was used only in California more than 40 years ago. Pesticide that a farmer had sprayed decades ago on a field 1,000 miles away had just washed up on a beach only a few miles from my Seattle home.

The ceaseless movement of water and animals connects us. It connects land and sea, sun-drenched shallows and dark ocean depths, distant continents and even time.

But as much as the ocean is about movement, we also turn to the sea for a sense of stillness. And stillness, it turns out, characterizes the lives of many of Puget Sound’s fishes.

Some of you may know one of my favorite fish: the lingcod. Besides being delicious, they are an important top predator in Puget Sound; on average, only killer whales are higher on the food chain in Puget Sound. But what else do we know about them? For properly managed fisheries, it is essential to know where fish live, what habitats they use and how far they travel.

To get at this, NOAA captured fish and inserted tiny transmitters into their bodies. We could then track their movement day and night for months. We were amazed to learn that they hardly move – if they lived on a football field, their whole life would take place in the red zone of a football field between the 20 yard line and the goal line. A full-grown lingcod is half the size of a full-grown human; imagine if you spent your entire life – working, meeting friends, finding food, eating, everything – in an area the size of half a football field.

This isn’t something that is unique for lingcod. The same is true for many fish, including yelloweye rockfish and bocaccio rockfish that live right here in Puget Sound – and are on now the Endangered Species list. In fact, when we look at fish overall, we see that, despite some fabulous exceptions like salmon, fish have the smallest home ranges for their size of any vertebrate animal. A raccoon in the city has a home range of about 28 football fields, or 140 times the home range of a similarly sized lingcod.

Why does this matter? In the early 1980s, rockfish were not really fished commercially in Puget Sound, and some fisheries managers thought they would be a great resource to exploit. Rockfish are a mild, tasty fish and they quickly became popular. The rockfish fishery boomed – you could even see an explosion of rockfish recipes in locally published cookbooks. But fisheries managers didn’t know that rockfish do not move much, and they did not know they grow slowly, mature late and have long lives (yelloweye rockfish can live for 200 years!). All this means that rockfish are easily overfished. About ten years after the Puget Sound fishery boomed, it was shut down. After ten more years, three Puget Sound rockfishes were on the Endangered Species list.

So, many fish basically stay home their whole lives. These fish can’t escape the effects our activities have on their homes.

New brain research is showing that our brains are hardwired to react positively to the ocean, and that being near it can calm and increase innovation and insight. It’s not surprising, then, nearly three billion people globally live within 60 miles of a coast, or that population growth along coasts is six times greater than inland areas.

As more and more people come to the shore to seek solitude and inspiration, we must let the sea teach us. Let it remind us that we are connected – that how we act transcends space and time. And for animals that can’t just get up and relocate, the consequences of our actions can be dire or provide solutions that make our piece of the world a better place.

Learn more about our Ocean Work

The Many Gifts of Herring in the Emerald Edge

Nature signals spring. In Texas it is blue bonnets, in New England, robins, and for the Emerald Edge of Alaska, British Columbia and Washington, it is the return of herring.

Written & Photographed by Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

For millennia, Pacific herring have been harbingers of spring. Historically, they returned in great numbers to spawn on kelp, seagrass and gravel throughout the Pacific Northwest. Their arrival was quickly followed by horde of sea lions, humpback whales, seabirds, and eagles all gorging on this plentiful prey. And in their wake, killer whales arrived to eat the sea lions and whales. With the arrival of herring, the waters of the Emerald Edge erupt with life.

And for the indigenous people of the Emerald Edge, herring eggs bring the first pulse of fresh food of the season. For the Haida, Tlingit and many other peoples, herring eggs are perhaps second only to salmon as the most culturally revered food. The Haida gather herring roe on kelp, while Tlingit set hemlock branches in the water and collect the thick layers of herring eggs that coat the limbs. Those who gather the delicacy will eat it themselves, share with family and friends locally and in distant communities, or trade for other products. Every feast and celebration will be accompanied by mounds of bright herring eggs that connect people to each other, their past and to the ocean.

Herring also signal the opening of the fishing season for commercial fishers. Many fishers who latter will focus on the lucrative salmon fishery, start their year with herring. In Southeast Alaska, over the last decade these boats scooped up an average of about 13,000 tons, annually. The unspawned roe is coveted in Japan, and in recent decades this has become a lucrative market. Both the income generated by the herring and the opportunity to break in new crew at the beginning of the season are critically important for many fisherman.

Herring are thus central for nature, for culture and for the economy of coastal communities. However, historic overfishing, pollution, coastal development and climate variability have resulted in many declining stocks of herring. In some places, the number of fish is so low that fisheries have been closed for years. In recent times, then, herring has not only announced spring, but has also marked a time of conflict.

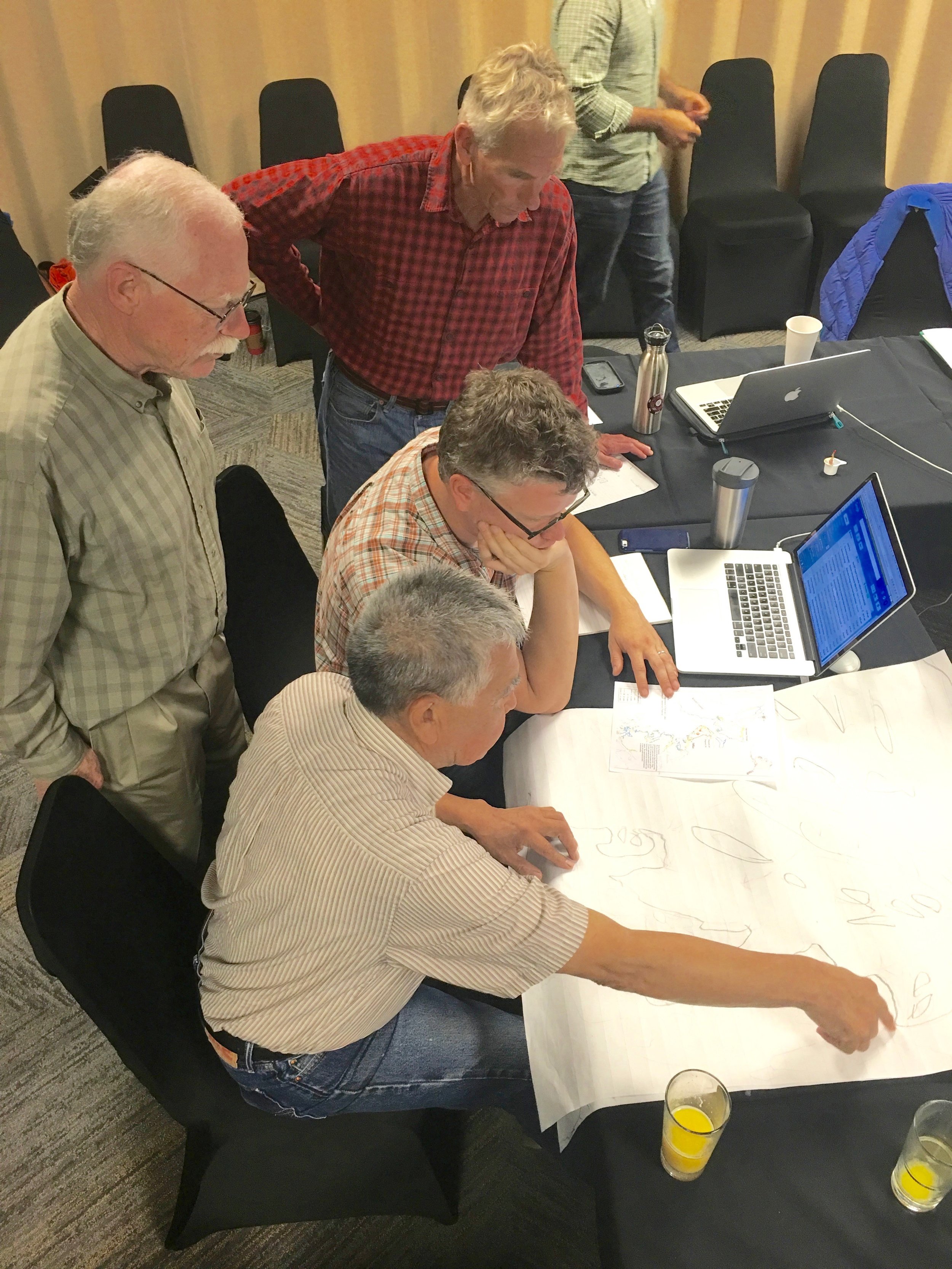

Last year, my colleagues from the Ocean Modeling Forum (OMF) and I brought together more than 125 First Nation and Tribal Elders, governmental officials, scientists and environmental NGOs and asked what were the critical science gaps for science management. As one of the directors of the OMF, my role is to connect diverse types of knowledge and bring it to bear on pressing ocean management issues. In the case of herring, we learned that the extensive traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often marginalized in management, and the cultural costs and benefits of herring are not adequately considered in decision making.

To fill these gaps the OMF created a working group of 18 social and natural scientists, traditional knowledge holders, commercial fishers, and resource managers to tackle this problem. I just returned from co-chairing the 3rd meeting of the OMF herring group (with Dr. Tessa Francis from the University of Washington Puget Sound Institute) which met in Sitka, Alaska. The group has made great strides in incorporating traditional knowledge into quantitative ecological models – the language of fisheries management. Working collaboratively across our professional silos, we have developed the means to formally examine management alternatives to determine their ecological, economic and cultural outcomes—the triple bottom line.

After the OMF meeting concluded, I had the privilege of visiting historic and current herring spawning grounds with Harvey Kitka – an elder of the Sitka tribe. Each cove and beach seemed to have a story of plenitude and demise. Harvey spoke about the time when herring were so abundant that they jumped from the water and the crack of their bodies hitting the ocean’s surface would echo across the Sound like hail. Those days are gone. Instead, Harvey pointed to islands were there was just a little spawning here and a little spot there. He spoke with sadness about the present, but was always optimistic about the future, and the work we are trying to do.

Solving difficult conservation problems, like herring conflicts along the Emerald Edge, will require new approaches and innovative thinking. My experiences working with a diverse group of people with vastly different perspectives on herring, suggest that given the chance people can rise to the occasion and tame these wicked problems.

Learn more about our work in the Emerald Edge

Anchors and Sea Change: A Fisherman Poet

Written by Kara Cardinal, Marine Projects Manager for Washington

Photographed by (1) Pat Dixon and (2) Dwayne Overhoff

“Fishermen communicate with as few words as possible,” says Rob Seitz, a fisherman from Morro Bay, California. “Things are much more simple and straightforward on a boat.”

The Nature Conservancy has been working with Rob Seitz over the past few years – first through the Conservancy’s California Coast Groundfish Project, where fishermen are helping to pioneer the development of cutting-edge science and conservation tools, forging collaborations and engaging in market initiatives that encourage long-term stewardship of our oceans. Washington is now working with Rob to scope opportunities similar to those in California. He has many contacts throughout the fishing community and will be helping the Conservancy engage with fishermen and community leaders to establish sustainable fishing practices along the Washington Coast.

With a vision of sustainable fishing and fishing communities, Rob and his wife, Tiffani, founded South Bay Wild Inc., a small, family owned and operated commercial fishing vessel using a triple bottom line approach and dedicated to harvesting high quality, sustainably caught seafood.

And on top of all that, Rob is also a “fisherpoet”! He has written and published a short book of poetry and prose that chronicles his life as a commercial fisherman and is a regular participant in Astoria’s Fisherpoets Gathering, which is held annually during the last weekend in February.

This poem he is sharing with us, Anchors, Change & that 92’ Dodge, was written during his work with the Conservancy’s Groundfish Project. He suggests that, during times of change, anchors ground you in tradition and a core set of values. But change will always be a part of life. We must be willing to accept and embrace it - for it may open up unexpected opportunities, and perhaps lead you to the fish! Enjoy this poem and be sure to check out more by Rob Seitz.

Anchors, Change & that ’92 Dodge

On the ocean everything’s always moving, even when it appears to be sitting still.

You’ll find out if you stick around long enough, this constant change can test one’s skill.

When ocean and events move too fast, you’ll need an anchor you can throw,

to buy time to take inventory, assess, how to avoid the rocky shore.

That old ’92 Dodge is an anchor of sorts I’ve found,

when life gets moving too fast it ties me to solid ground.

See, grandpa’s last truck was my first, when he died he left it to me.

With a note that read, “take good care of my truck & it’ll be the only one you ever need.”

So when I find myself thinking too hard and my auto-pilot can’t see,

I go for a ride in that old truck and Gramps comes along to council me.

He says, “Ya know boy when you got your head up your ass, installing a transparent belly-button might help you to see.”

“But pulling your cranium out of your rectum makes a lot more sense to me.”

“You’ll find tomorrow comes sometimes, and it’s better to be wise than bold, take good care of yourself just in case you happen to get old.”

“The thing about those radio-fish is they’re already in somebody else’s hold, turn down the volume, pay attention to the signs, figure out where your boats gotta go.”

“You’ll see in time, the fisherman who has the better luck, ain’t always the one who’s driving the newest truck”

“Sometimes money’s tight and flashy don’t pay the bills, the less you owe, the less you need, and the fewer fish you gotta kill.”

“So, maintain what you’ve got, might not be pretty but it’ll do, remember, when it’s a hard pull, slow and steady gets you through.”

“And those fish, they’re like you & that truck, you gotta take care of the sea, or you’ll find yourself on the side of the road, thumb in the air, without a fishery.”

“Truth isn’t always popular, and life ain’t just about collecting wealth, let the idiots point and laugh, just make sure you’re true to yourself”

Now, I don’t always like hearing what Gramps has to say, but he’s pretty much always right, a couple of times if he wasn’t already dead, I’d have invited him out of the truck for a fight.

So it is, each generation grinds to the next, when my turns over I wish those left luck. And I’ll leave ‘em with one word of advice; take good care of that old truck.

While the Conservancy has greatly valued the knowledge and experience that he brings to the table, Rob has also found value in working alongside the Conservancy.

“The Conservancy has helped me learn how to help myself – by learning how to communicate. I began to learn the process – both the fisheries management and marketing – and this has brought me and the industry a lot further toward our goals.”

Rob recognizes that the Conservancy is working to improve fisheries management in a sustainable way, bringing the small, independent fishermen along with us. “This is the best way of bringing the next generation into the fishery” he says. We think his grandpa would agree, for “you gotta take care of the sea.”

Protecting the Little Guys (Because they’re so tasty!)

Story by Paul Dye, Director of Marine Conservation

Photography by Erika Nortemann

The Pacific Fishery Management Council—the body that creates fisheries regulations for federal waters off the West Coast—did a wonderful thing this week. They declared a large number of fish and squid species off limits to targeted fisheries until we know what the impacts of a new fishery would be. All of the protected species are small, and they’re known as “forage”species because so many other animals eat them. They provide a vital link in the ocean food chain that starts with sunshine and algae and tops out with fresh fish on our menus. The new protections will help ensure that seabirds, whales, seals and sea lions, and the bigger fish that people typically catch and eat will all have a healthy and sustainable food supply.

I have been pleased to play a small part in this innovative example of ecosystem-based fishery management. I chair the Council’s Ecosystem Advisory Subpanel—a group of volunteers representing the people of Washington, Oregon and California who care about the sustainability of our fisheries and the health of the ocean. Some of us are scientists, others are commercial or recreational fishermen, conservationists, or have retired from one of these fields. Over five years, most of the work to develop the new management measure fell to fisheries scientists and policy experts working for government agencies. Our subpanel ensured that a broader range of perspectives guided that work.

The new measure has attracted nearly universal support from commercial and sport fishermen, the seafood industry, retailersand restaurants, and environmental groups. That is a good sign that we are getting smarter about how to use—and conserve—our ocean resources.

Read the full story on EarthFix!

You can learn more about our marine work.

Related Blog Posts