By Brian Straniti, Central Cascades Community Coordinator

Working for The Nature Conservancy awards numerous areas of gratification. Engaging in projects which aid in restoring our lands and waters, and sharing them with the public, offers a sense of fulfillment I have not experienced at other places of employment. As such, receiving a request from NASA one uneventful afternoon while sitting at my desk elicited a, “Wow, I have a cool job” emotion from this Sci-Fi geek.

Unfortunately, NASA was not reaching out to offer me an interstellar ride on a new fusion engine ship that can reach one-tenth the speed of light. Rather, I was being asked to participate in their DEVELOP program. The program offers a professional opportunity to a diverse pool of young candidates to bridge NASA Earth observations and environmental issues.

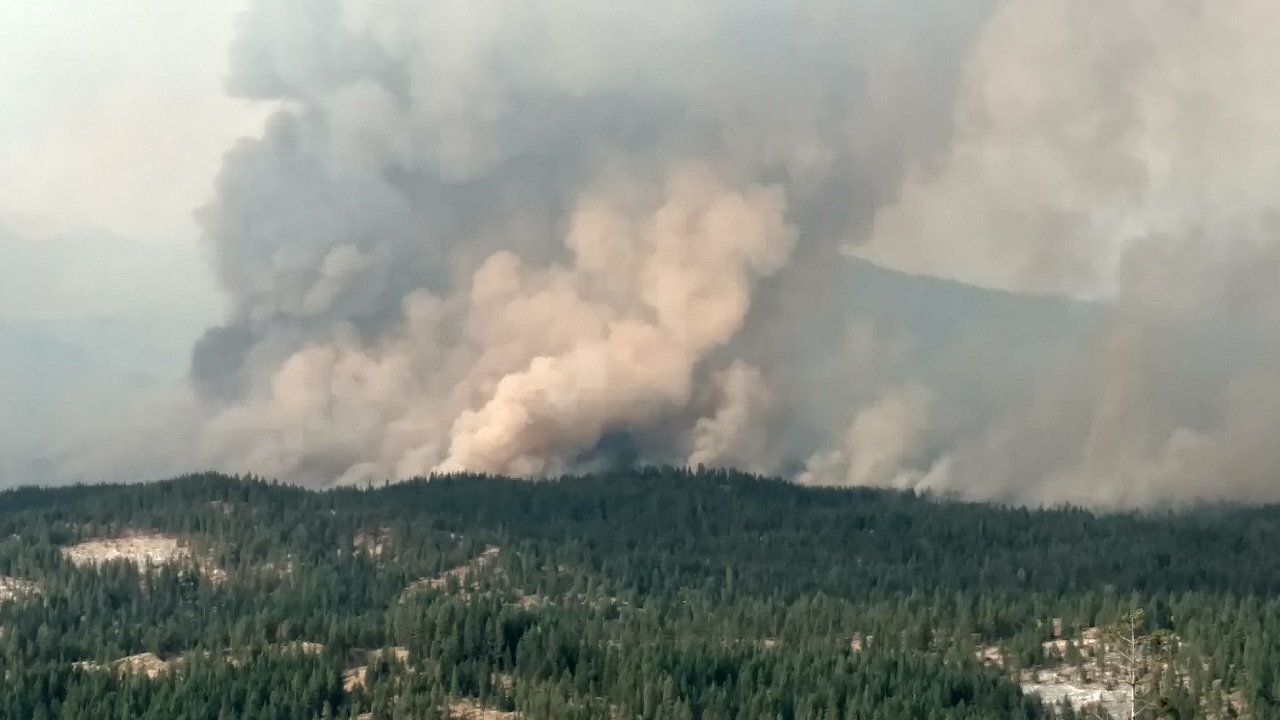

Smoke from the Jolly Mountain Fire in 2017 near the town of Cle Elum. Photo © John Marshall

The program coordinator, after doing some research regarding the challenges of restoring a dry forest landscape to its natural state, saw this as a perfect opportunity to apply satellite information with powerful geographic information system (GIS) tools to complete a research project to better inform local land managers on target areas to initiate forest health projects.

Two of our top priorities in Eastern Washington are forest health and partnerships. We were able to thread both priorities as we began this partnership with the NASA DEVELOP Eastern Washington Disasters team. The team partnered with The Nature Conservancy’s Washington chapter and the Washington Department of Natural Resources Southeast Regional office to analyze the relationship between lightning strikes and wildfire events in Eastern Washington, with an emphasis on Kittitas and Yakima counties.

Researchers with NASA DEVELOP (clockwise from top left): Ani Matevosian, Amelia Zaino, Evan Bradish and Amy Kennedy

After meeting with the intrepid researchers, Ani Matevosian, Amelia Zaino, Amy Kennedy and Evan Bradish—and being immersed in a feeling of hope for the future through these gifted young individuals—my interest in the project accelerated. Lightning is nature’s catalyst for forest fire. But historic fire suppression methods and over-harvesting have left Eastern Washington vulnerable to large scale, high-intensity wildfires—so while the ignition source may remain the same, the resulting devastating fires are strikingly different and pose more dangers than a century ago.

This project uses NASA satellite technology to gather data on lightning strike frequency and vegetation moisture, then compares those datasets with historical fire information to compile a ranking of the most vulnerable areas. This information may help land managers to decide where best to engage in forest health practices, such as fuels reduction and prescribed burning.

View a story map in the embedded view below:

This research provides a lens to the importance of restoring our forests to their natural fire-adapted state, when fire passed through, offering a service. Low- to medium-intensity surface fires—which burn brush and small-diameter trees but leave large, resilient trees—were part of the natural ecosystems’ function by reducing understory fuels and opening serotinous pinecones, which can hang on a pine tree for many years while the seeds inside mature. When a low-intensity fire passes through, these heat-dependent cones open and release their seeds, broadcasting a message that fire is a part of our ecosystem.

A ponderosa pine stand in the Sinlahekin Wildlife Area in Okanogan County. This forest has been thinned of small diameter trees and brush and a prescribed fire was set to reduce fuels. This photo was taken 5 years after these forest treatments. © John Marshall

Additionally, ponderosa pines, which dapple the landscape on the dry side of the Cascade Range, have flaky bark that withstands a low-intensity surface fire. As the ponderosas age, they also drop lower branches, which helps prevent fire from climbing up and burning the green crown of the trees needles atop the ancient sentinels—which could cause the fire to gain intensity.

Prescribed fire in ponderosa pine forest in the Sinlahekin Wildlife Area in Okanogan County. Low and medium intensity fire is a natural disturbance event that promotes the health of dry-forest ecosystems. © John Marshall

With these natural conditions, and obvious presence of lightning in a dry environment, human intervention is needed to reduce the size and intensity of naturally ignited forest fires. Reducing fuels through mechanical thining of small trees and through prescribed fire is our primary method to do so.

I am proud to have completed this project with these brilliant individuals, who honestly did all the work, to better inform land managers at The Nature Conservancy in Washington and our partners to identify critical areas where the work is most important. Perhaps, if we continue this relationship, next time they will reach out with an important space mission!