This article was published in our state chapter magazine, Washington Wildlands, in Spring of 2007, to mark Victor Scheffer’s 100th birthday. Dr. Scheffer was one of the founding members of the Western Washington chapter of The Nature Conservancy.

By Gestin Suttle

You feel almost silly asking Victor “Vic” Scheffer why he thinks it’s so important to protect our state’s natural areas. It’s a little like asking him why he thinks it’s so important to breathe. “I’m a card-carrying naturalist. Naturalists like to save things,” Scheffer said recently from his home at University House in Wallingford.

Scheffer, who turned 100 in November 2006, is a founding member of The Nature Conservancy’s Washington chapter and arguably the state’s longest-living conservationist.

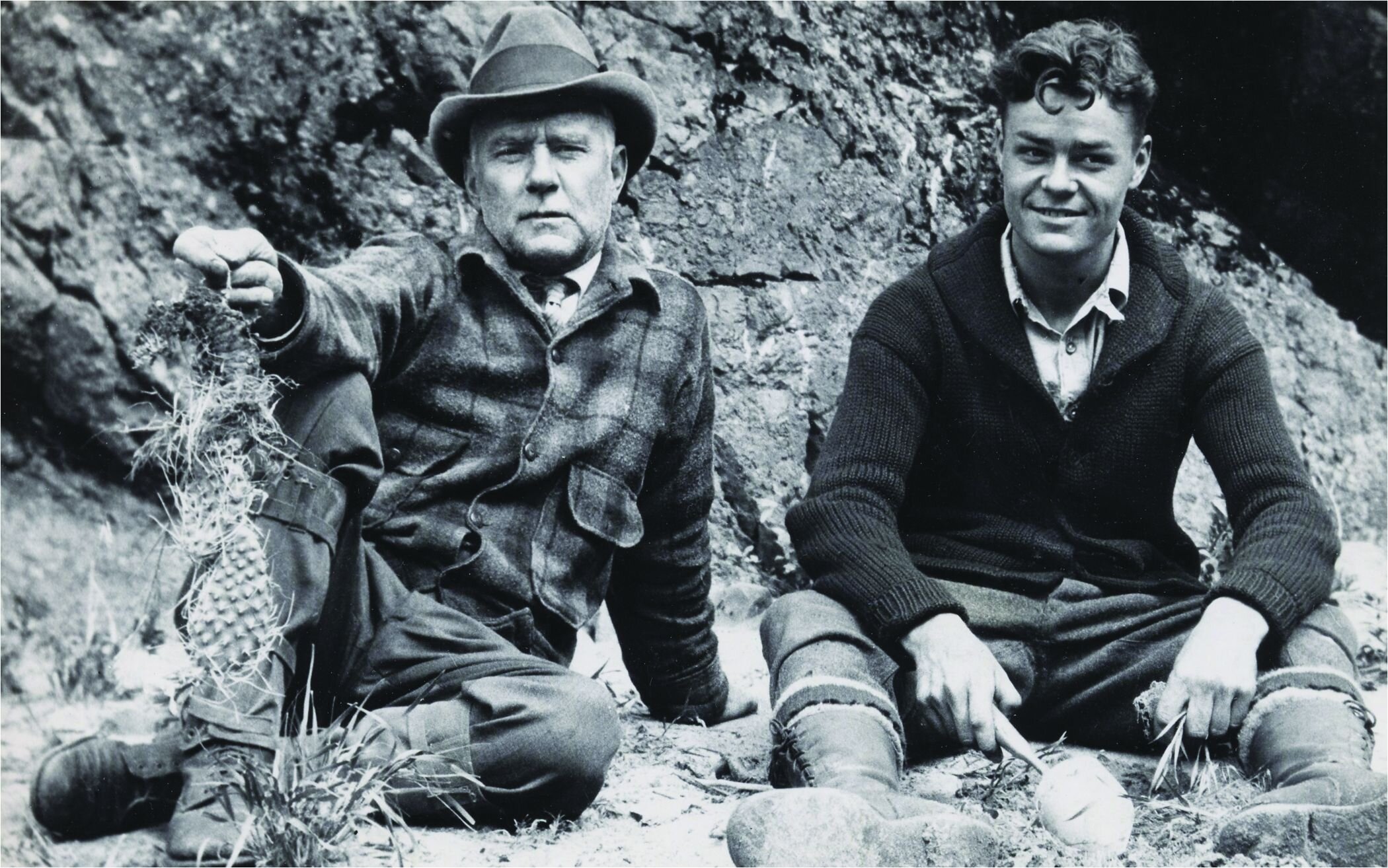

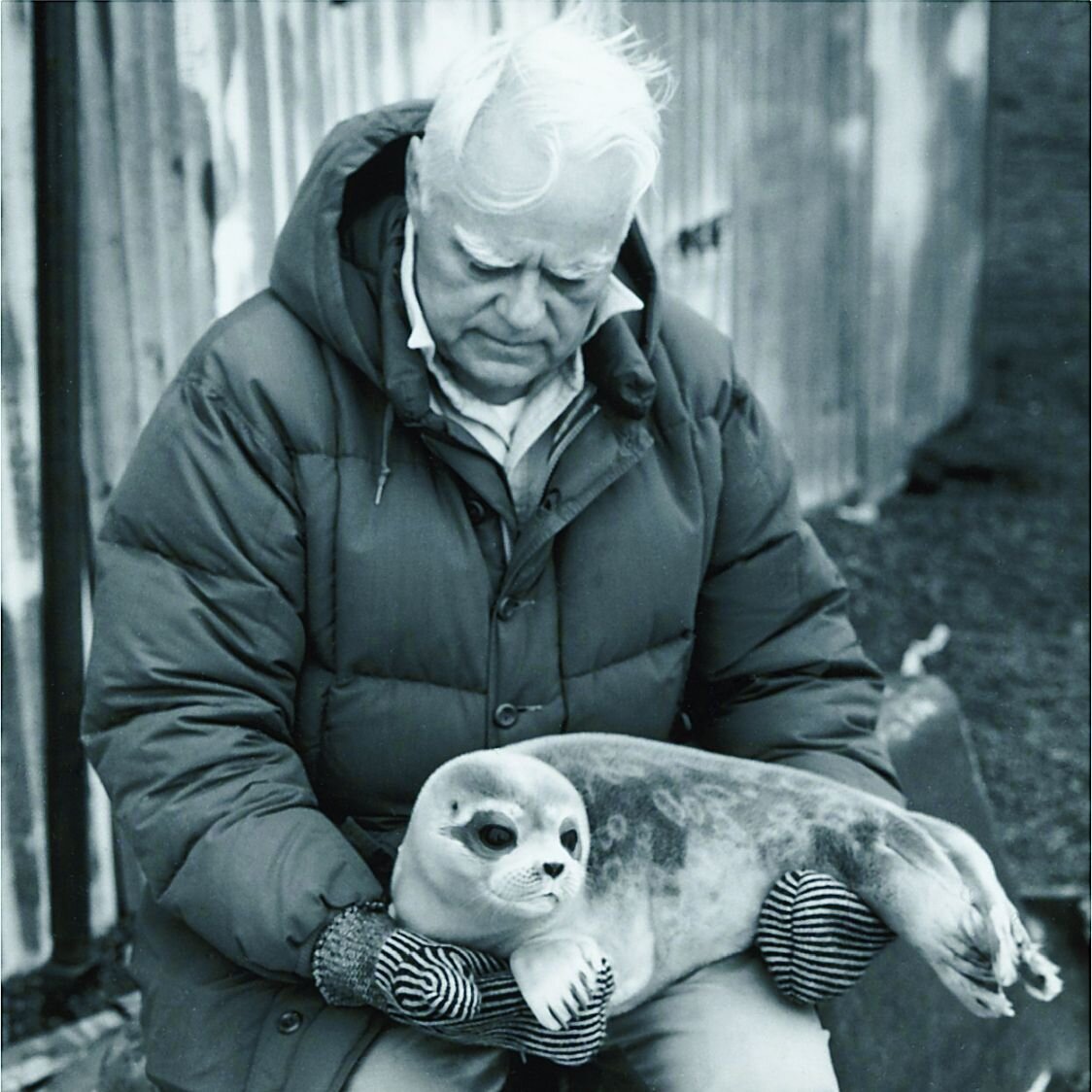

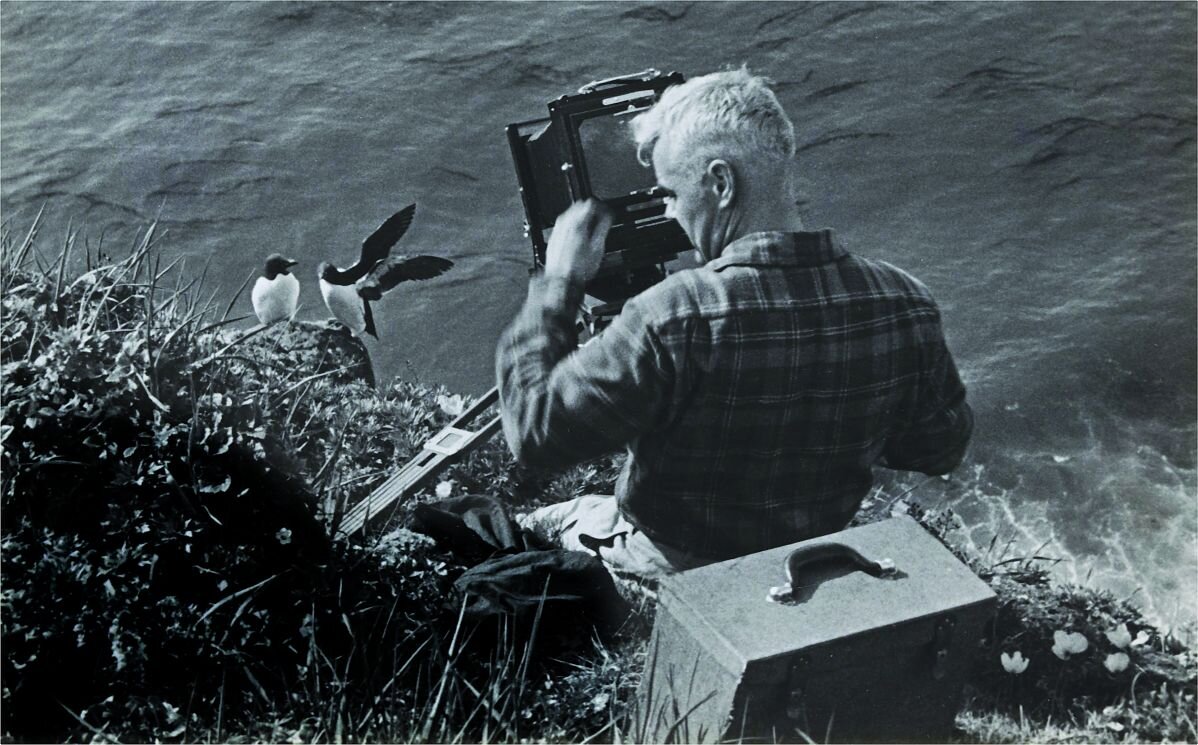

Photos above show, from left, a young Vic Scheffer in the field with his father, Scheffer, author of several books on marine mammals, with a seal, and Scheffer photographing auklets in the field. Photos from University of Washington Special Collections.

The former University of Washington professor, photographer, and author was among 14 concerned citizens who gathered in Bellevue Mayor Charlie Bovee’s home in 1958 to organize the Conservancy’s local office. The national organization had been incorporated on the East Coast in 1951.

Among the scientists involved in the chapter’s start was Art Kruckeberg, a former UW professor of botany, who recently joined Scheffer and his daughter, Ann Carlstrom, for lunch at Scheffer’s home. They came to feast on the memories of the Washington chapter’s earliest days. Although Scheffer’s vision has dimmed over the years, his eyes still gleam and his memory remains sharp —especially when it comes to recollecting the Conservancy’s beginnings.

Scheffer easily recalled how he and his cohorts got to work saving some of Washington’s most treasured natural spaces, including Cypress Island in the San Juans, Foulweather Bluff Preserve near the tip of the Kitsap Peninsula, Carlisle Bog in Grays Harbor County, and the Mima Mounds south of Olympia.

To draw attention to the value of Cypress Island, Scheffer, Kruckeberg, and Frank Richardson, a fellow UW zoologist after whom Frank Richardson Wildfowl Preserve on Orcas Island is named, cataloged the diverse species of animals, plants, and birds on the island. Their work helped persuade the state’s Department of Natural Resources to preserve Cypress Island, which today remains the last largely undeveloped island in the San Juan group.

The scientists took a similar approach to the other areas they sought to preserve. They highlighted what policymakers already knew was happening.

“I don’t think we ever lobbied,” Scheffer explained. “Decision-makers were realizing that natural sites were going rapidly to development.”

Scheffer was the first scientist to draw attention to the Mima Mounds south of Olympia. He had learned about them in the early 1940s, when Walter Dalquest, a graduate student, convinced him to go see these peculiar formations. Scheffer’s first thought upon seeing the mounds? “Wow!” he said.

Scheffer later chartered a plane so he could see the mounds from the air. The site of the uniform spacing and size of the mounds “confirmed my belief that it could only be the territorial expression of some animal” that created them, Scheffer said. He and Dalquest developed the theory that prehistoric gophers created the formations. It remains one of several theories explaining the origin of the mounds.

The Conservancy stepped in to protect the mounds until the state Department of Natural Resources took over. Today the 445-acre Mima Mounds Natural Area Preserve includes an interpretive trail and is home to one of the country’s rarest ecosystems.

Scheffer remains most proud of the work he did to preserve the Mima prairies. “They’re like a field of giant eggs, half buried in the ground,” he said.

Such a keen eye has contributed to Scheffer’s other great passion, photography. His photo collections from 1918-1976 are housed in the Special Collections division of the University of Washington Libraries. In 1971 he published The Seeing Eye, which makes use of his artistic photographs of nature to study color, form, and texture. Scheffer has published 13 other books, including Seals, Sea Lions, and Walruses; The Year of the Whale and The Year of the Seal.

To what does Scheffer attribute his successful career? “A sense of wonder,” he said.

“He never stops ‘wool-gathering,’ as my mother would say,” explained Carlstrom. She fondly recalled how her father painstakingly cataloged his photographs, which today number more than 9,000. “Any pictures of us kids were filed under ‘mammal,’” she laughed.

“What’s wrong with that?” Scheffer responded.

His passion for his work was pervasive, Carlstrom said. “You never knew, if you grabbed the cottage cheese container out of the refrigerator, if you’d find cottage cheese, or maybe a mountain beaver fetus,” she said.

The retired scientist credits his father for both his intense interest in the natural world and his long life. Scheffer’s father Theophilus “Theo” Scheffer was a biologist for the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey. His work centered on wildlife management in the Pacific Northwest, and he lived to the age of 99.

Kruckeberg thanks Scheffer for helping to make preservation a top priority in Washington. “He set the stage for later conservation efforts,” Kruckeberg explained. “He’s been an inspiration.”