We live in a region known on bad days for rain and traffic. The combination of the two creates a particularly toxic problem in our region: polluted runoff. The sheer vastness of our road system poisons local waterways and makes them more challenging to treat. Thankfully, we have a solution: treat it with compost! Green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) uses organic soils and native vegetation among other tools to filter pollution from runoff before it reaches rivers, lakes, and Puget Sound.

The Nature Conservancy’s recent report “Retrofitting Our Legacy” offers five common-sense policy strategies for cities and counties to ramp up their use of GSI to tackle runoff pollution at the scale of our road system.

Go Big, Because Home is Polluted – Evaluate the entirety of the watershed to prioritize toxic hotspots and treat stormwater with regional facilities.

Make GSI Easy – Make policy changes to reduce barriers and boost GSI and hybrid gray/green retrofits for water quality at city and county levels of government.

Show Me the Money – Incentivize investment in stormwater retrofits for roads that deploy GSI.

Maximize Impact with Multiple Benefits – Build GSI projects that support communities in ways beyond stormwater. Think parks and community gardens!

Build Decision Maker Support – Accurately value and communicate the benefits and costs of GSI and hybrid grey/green solutions, including co-benefits like flood control and green jobs!

From car tires to our local waterways, research has shown that 6PPD is toxic to salmon. © Leslie Carvitto

Busy highways and roads are the largest sources of stormwater pollution to Puget Sound, poisoning our ecosystems with heavy metals, excessive organic materials, toxic chemicals and car tire dust. That car tire dust contains a chemical preservative in rubber known as 6PPD, which is deadly for our native salmon. Rain washes this pollution, including 6PPD, into our waterways.

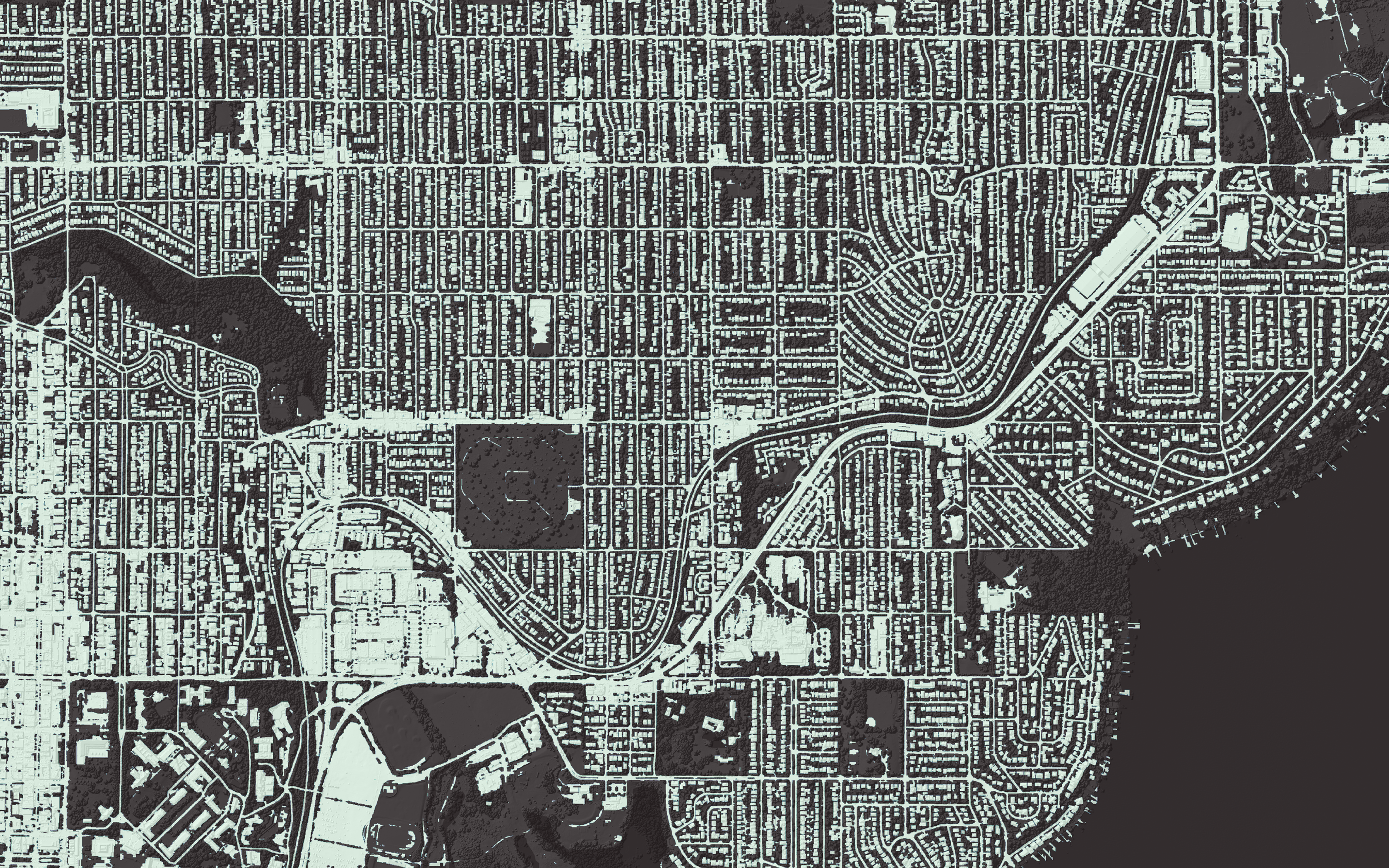

Unfortunately, our stormwater pollution problem is as big and spread out as our road system. That’s a wide area to treat, especially after decades of building roads with storm drains designed to move untreated runoff into rivers and Puget Sound as fast as possible. Cities and counties are responsible for stormwater but don’t have the infrastructure necessary to treat it at the scale to improve water quality, and Washington’s stormwater permits don’t require them to do so.

Six years ago, The Nature Conservancy began gathering strategies and case studies for ways cities and counties can treat road runoff pollution above and beyond permit requirements. At the time we already knew that road runoff was a leading source of pollution to our waterways, a threat to salmon, and that GSI can effectively treat road runoff.

Since then, local scientists discovered 6PPD was killing coho salmon, and cities and counties have built several stormwater parks in the region. This is progress, and it needs to become the norm rather than an exception.

So, where does the compost come in? Well, when dirty stormwater water filters through organic soils with plants and microbes, most of the pollution latches onto these natural elements and begins breaking down. Clean water percolates out. This is bioretention, a form of GSI. But GSI can treat stormwater at many scales, from a raingarden for a single roof, to roadside swales, to regional stormwater parks that treat runoff from hundreds or thousands of acres in one place. Even better, using GSI creates multiple benefits beyond water quality, from new park spaces to improved mental health and urban habitat.

The bioswale under Seattle’s Aurora Bridge treats nearly 2 million gallons of stormwater annually and serves as a scenic community garden landscape. © Courtney Baxter/TNC

“Retrofitting Our Legacy” offers ways to accelerate stormwater treatment, while removing barriers and benefitting local communities. Each strategy has specific examples and case studies, with links to further resources. Using these strategies, everyone from homeowners to stormwater managers can work at scale, find new ideas, and strengthen community well-being. It is past time for cities and counties to build more well-placed ditches, ponds, and compost-filled concrete boxes to treat toxic hotspots at the scale of our road system. Doing so will support our native salmon populations and bring community benefits beyond clean water.

Featured photo: Rain garden below street. Credit: Michael B. Maine/TNC