By Emilie Pilchowski, Doris Duke Conservation Intern

Whose stories are shared on The Nature Conservancy preserves and whose are left out? Who do these stories serve and what message do they convey to visitors?

THE BLUFF TRAIL overlooking Admiralty Inlet. ©Emilie Pilchowski

SIGNAGE at Ebey’s Landing. ©Emilie Pilchowski

These two questions have been at the forefront of our research this summer as interns for TNC’s Stewardship program. As Doris Duke Conservation Scholars and interns under the guidance of TNC staff, Erin and I have been working to support TNCs work to begin re-centering the story of this land and to develop a more inclusive understanding of the area.

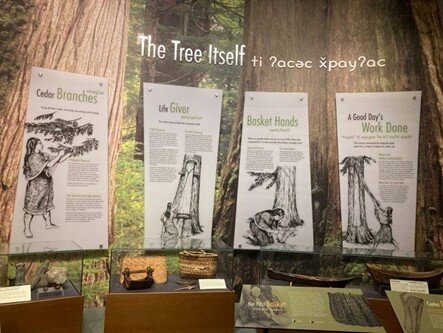

The Indigenous relationships to the land since time immemorial are deep part of Ebey’s Landing. As current stewards in this area, TNC doesn’t want to perpetuate the message that its history began with the arrival of Euro-American settlers. We seek to help ensure that the placenames, informational materials, and signage developed for the preserve will do a better job of reflecting the Indigenous histories and their present-day relationships to the area.

Our research led us to learn more about various inclusive signage projects, museums, and people across the Puget Sound. My takeaway from these visits is how deeply embedded Indigenous cultural practices and identity are within the landscape. I also realized that the history of places like Ebey’s Landing must not be considered as isolated events, but rather part of a broader geography of cumulative, multigenerational injustices against Indigenous communities, and a long history of activism and resilience.

The čičməhán trail.

As a private land trust, TNC manages and stewards lands that were previously shaped, stewarded and often home to Indigenous people. These Indigenous relationships to the landscape did not only exist in the past but are still very much present to this day. However, these lasting relationships to the landscape are often not represented on publicly accessible lands. By critically examining and interrogating the stories put forward on our preserves, The Nature Conservancy can begin the process of creating more inclusive spaces.

THE SUQUAMISH Museum. THE TULALIP Hibulb Center.

Over 200,000 people visit Ebey’s Landing and Robert Y. Pratt preserve every year. This gives our organization an important opportunity to amplify Indigenous histories and shape the narrative that visitors receive. We cannot do this by ourselves, however. We have to ask our Indigenous partners what they want to see here, what messages they want shared, and work collaboratively to respect those priorities. While this can be a long process to undergo, it allows us to shine light on the real history of the landscape, including the injustices of this history, as well as the systems of inequity within land ownership and management. The work must, however, continue beyond examination alone. Recognizing the injustices too long ignored should become a call to action to rethink the aims of conservation, and achieve a more just future. While past injustices have set the stage for conservation as we know it, we can re-imagine a conservation movement centered around equity, reciprocity, and hope.

THE BLUFF TRAIL at Pratt Y. Preserve. ©Emilie Pilchowski

Although we’re still in the very beginning stages of this effort, TNC is committed to achieving a more inclusive and representative story at Pratt Preserve and elsewhere, one that follows the lead of our tribal partners in order to serve these histories best.

I hope that the next time you walk along a TNC preserve you take the time to not only consider whose stories are highlighted within our landscapes and who these stories serve, but that these reflections also drive you to envision a more just future for every landscape.