Workforce development is a roadblock in the effort to implement nature-based solutions for climate resilience within Washington State and across the country. To address this challenge, experts and collaborations have identified challenges and solutions for workforce development within the green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) field.

The State of the Puget Sound Tree Canopy

Considering Climate for a Healthy Urban Tree Canopy

Meet Molly Bogeberg, Marine Conservation Manager!

Molly Bogeberg is a Marine Conservation Manager with The Nature Conservancy in Washington. She came to TNC as a Sea Grant Marc Hershman Marine Policy Fellow in 2014 after completing a M.S in Environmental Science at Washington State University. Molly’s work at TNC has covered a wide range of topics including coastal sea level rise and resiliency planning, derelict crab pot removal, aquaculture, and fisheries. Since 2017, Molly has also been working with a team to monitor and continue restoring TNC’s Port Susan Bay estuary preserve. While much of her workday is spent managing projects over email and Zoom, what she loves most about her work is time spent out of the office meeting with community members and time in the field. Molly is happiest when found covered in mud after a day on a shellfish farm or in the marsh with partners or co-workers! Outside of work, Molly enjoys hiking to see wildflowers in the spring and summer and skijoring with her dog, Sasha, in the winter.

Building Paradise: Community-led Solutions to Stormwater and Food Insecurity

A Snapshot in Time: Capturing Learning from Fish, Farm and Flood Groups

Trustee Lobby Day 2022

New Tools For Urban Trees

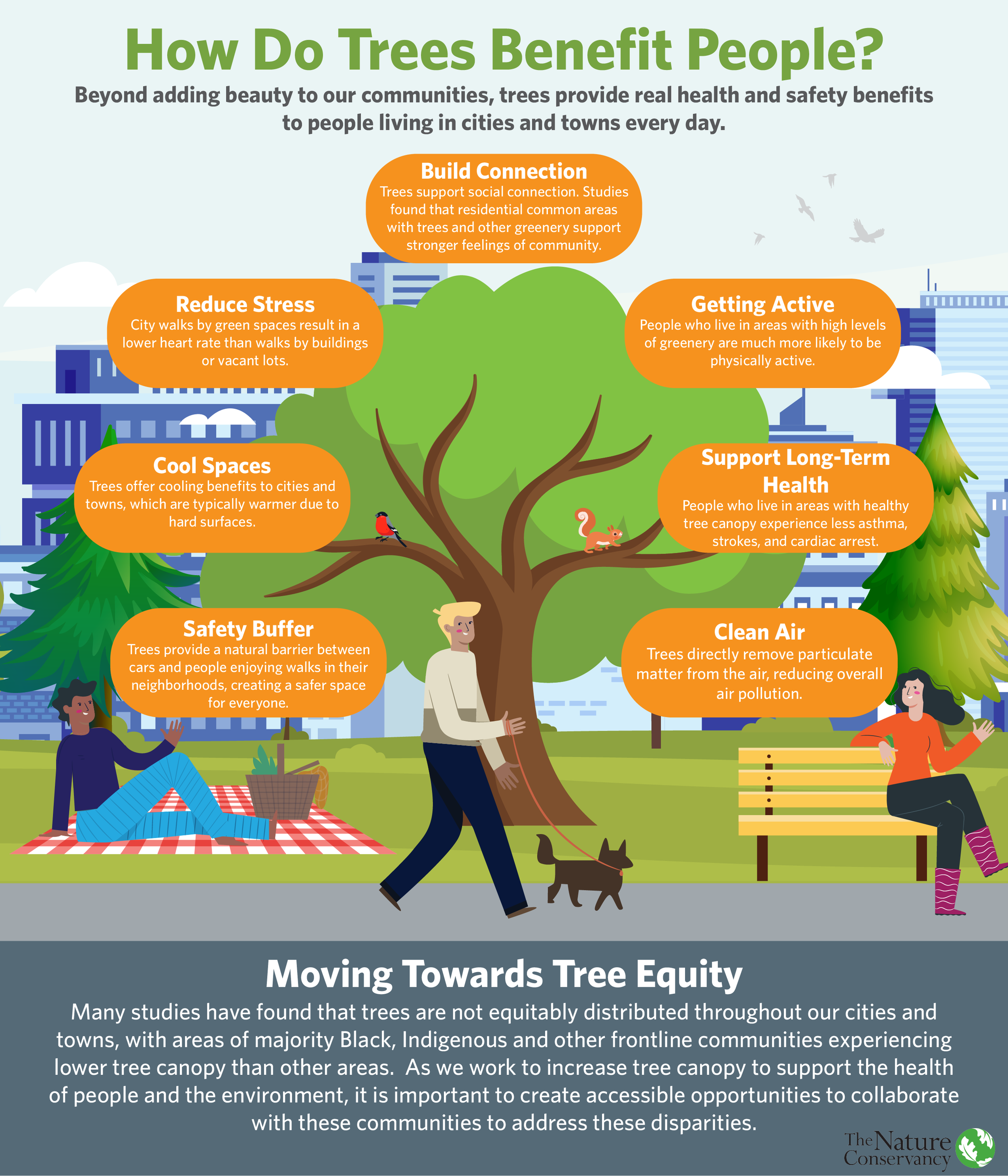

Health Benefits of Trees

Saving Salmon: You have to know where to work

Celebrate Communities Connecting to Nature

Beyond the environmental benefits, these spaces provide opportunities for people to connect and move forward the vision they have for their communities. From the Duwamish River Valley to Kent neighborhoods to Tacoma parks and streets to bluffs and shorelines around the Sound, Sarah Low, Tahmina Markelly, Whitney Neugebauer and Paulina Lopez are creating community and restoring our world.

Beyond the environmental benefits, these spaces provide opportunities for people to connect and move forward the vision they have for their communities. From the Duwamish River Valley to the bluffs and shorelines around the Sound,

Join us virtually with four inspiring women from around the Puget Sound region to celebrate Earth Month, April 21, 5 to 6 p.m. Each one is creating community and restoring our world.

City trees bring joy and other benefits

The Nature Conservancy has collaborated with partners throughout the Puget Sound region to support our urban tree canopy through planting, preserving and maintaining trees at residences, parks, schools and restoration sites. These projects are an opportunity to contribute to the health and resiliency of communities.

Water 100 – Engaging the Business Community to Regenerate Puget Sound

The Water 100 Project. is an initiative of The Nature Conservancy and Puget Sound Partnership. This initiative includes scientists, engineers and policymakers working together to identify the 100 most substantive solutions for a clean and resilient Puget Sound. Together, we are looking to integrate the resources and speed of the private sector to take meaningful action toward a water resilient future.

Dirt Corps is bringing green jobs to communities

Equity, inclusivity, and accessibility are cornerstones of Dirt Corps’ approach to conservation. The community-based project turned business began six years ago in South Seattle, when a group of community activists and environmental experts—many of whom were underrepresented in the conservation profession—coalesced around a shared vision for healthy communities and greater access to green jobs.

Restoring Ballinger Open Space

For years, a neglected 2.6-acre green space in Shoreline has sat adjacent to Ballinger Homes, a low-income subsidized housing community. This neglect has led Ballinger Open Space to be filled with invasive weeds that include knotweed, Himalyan blackberry and English ivy. A multi-pronged partnership aims to restore the health of this riparian area by turning back the clock, clearing invasive weeds and planting trees. This will increase access for young people to nature, cut air pollution and treat stormwater.

Beyond 60: For a Healthy Puget Sound, Partnerships are Pivotal

They knew it was a long shot.

Yet Washington tribes, agricultural interests, environmental groups and local governments showed up in the state Capitol and spoke with one voice: The state, they told legislators, should invest $33 million to meet the needs of this diverse set of stakeholders. Their interests may vary, they noted, but they are connected by the floodplain where they live and work. Investing in a novel approach to collaboratively manage floodplains could protect communities and farms from flooding, sustain endangered salmon runs and create appealing places for people to enjoy the outdoors.

Lawmakers listened. In fact, they liked the idea so much that they allocated $44 million, a third more than requested. That 2013 funding launched the first suite of Floodplains by Design projects.

“We had all these different interests asking for the same thing,” said Bob Carey, The Nature Conservancy’s director of strategic partnerships. “That’s unique, and it opened some eyes. And getting more funds from the legislature than we requested? It’s unheard of!”

Since then, Floodplains by Design has won an additional $121 million in state funding for projects that have protected 38 communities and hundreds of residences, conserved 500 acres of farmland, and improved habitat for shellfish and salmon, among other benefits.

Aerial view of the Skagit River Delta where restoration projects have included Fisher Slough, Livingston Bay, and Fir Island Farm. Photo by Marlin Greene/One Earth Images.

“The way we manage our rivers has implications for farmers, tribes, conservationists, residents and civic leaders,” said Laura Blackmore, executive director of Puget Sound Partnership. “Floodplains by Design brings these interests together in a sophisticated and holistic approach that produces better outcomes for people and nature.”

That partnership-driven approach has become increasingly critical to the Conservancy’s success as we’ve scaled up our ambitions over 60 years. From our scrappy beginnings preserving important but often isolated parcels of land, we’ve evolved to focus on restoring healthy ecosystems that sustain both wildlife and human well-being. Today, we have set our sights on conservation throughout the Puget Sound watershed, from its robust floodplains to vibrant cities. But we can’t achieve results on that scale on our own, or even by working only with other conservation interests.

In much of our work, this calls for creative collaborations:

“We learn as we pioneer new approaches. Then we find the path of least resistance and greatest impact,” said Jessie Israel, our WA director of Puget Sound conservation. “The power of our partnerships fuels this innovation, and collaboration is the key to a healthy, thriving Puget Sound.”

Conservation through Collaboration

One of the very first Floodplains by Design projects demonstrates how communities rally around projects with multiple benefits for people and nature.

In the fall of 2014, the city of Orting had just set back its levees on the Puyallup River when the largest flood in decades hit. Only a few years earlier, another large flood had forced one the largest evacuations in state history. This time, the river had enough room to spread out and absorb the downpour. The town was spared.

“The benefits to people are obvious and immediate: safety, community well-being, economic security,” Orting Mayor Joachim Pestinger wrote in a 2015 op-ed in the Seattle Times.

Flooding risk is growing throughout Western Washington. This photo is from a 2015 flood in Snoqualmie, WA. Photo by The Nature Conservancy.

“Salmon also are taking advantage of their new 101 acres of habitat,” he wrote. “The wider channel provides opportunities for the river to meander and create complex habitat, with refuge for juvenile salmon in channels with lower velocity during peak flows. Birds and other animals enjoy the new wetlands, and people are taking advantage of new trails. While this project may not remove the risk of all future flooding, it is vastly improving our quality of life.”

That early success has blossomed into a much larger collaborative effort along the Puyallup River. This offshoot, called Floodplains for the Future, is a coalition of the county, cities, tribes, agricultural and environmental interests that are now implementing dozens of projects up and down the river corridor.

Being at the same table has allowed these groups to find common ground. A proposed flood mitigation project by the city of Sumner, for example, had been stymied because the Muckleshoot and Puyallup Tribes did not see their perspectives represented in the plan.

“City leaders pivoted... and sat down with tribes and others and figured out how they could address the very serious flood risks in ways tribes could support,” Carey said. “Now it’s a much more ambitious, multi-benefit project that people are excited about.” The project is underway, supported through Floodplains by Design funds.

This collaborative approach is much different — and harder — than what usually occurs, Carey said. Traditionally, groups have developed plans focused on a single purpose, for example, restoring salmon habitat. “But then when you go to implement,” Carey said, “the people affected by that project are like, ‘Wait, wait, wait; that’s not what I want to see there.’”

Floodplains by Design projects improve salmon habitat while also protecting Tribal and agricultural lands from floods. Photo by BLM.

That’s why successful ecosystem management requires “building trust and respect, and really listening to folks to understand what their needs are,” Carey said. “And then embracing those needs in the plan that you craft—in partnership with the other interests at the table.” While it may be harder to develop a plan that multiple interests support, collaboration can ultimately facilitate implementation while generating a much higher return on investment.

Today, Floodplains by Design has become a model for floodplain management around the world. With climate change driving increased flooding, innovative approaches like this are increasingly important. Carey and his colleagues have presented to Conservancy chapters and floodplain managers around the U.S., and in Canada, China and New Zealand. The language of multi-benefit solutions pioneered by the program now infuses conversations among floodplain managers, conservation organizations and state and federal agencies, Carey said.

Nature in an Urban Landscape

To have an impact on the scale of Puget Sound, we had to invest not only in its tributaries, but in the cities and towns that surround this iconic water body. Drawing on Floodplains by Design’s lessons in collaboration across sectors, we launched our Cities program in 2016.

"A thriving Puget Sound requires successes at the street and neighborhood level,” said Chris Hilton, the Conservancy’s urban partnerships director. “And it also requires the regional vision that the Conservancy brings, the ability to identify common problems and help communities generate solutions.”

A rain garden under the Aurora Bridge in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, where polluted stormwater will be naturally filtered before flowing into Lake Union. Photo by Hannah Letinich.

Our Cities program engages communities to make the Puget Sound’s urban landscapes more livable and climate resilient. In particular, our focus on stormwater pollution implements bioswales and raingardens to filter toxic runoff from busy streets and highways. As climate change increases rainfall in Puget Sound, the stormwater challenge is becoming increasingly urgent. Through a lens of equity and environmental justice, we also partner with local organizations to enhance the urban tree canopy, build rain gardens to purify polluted stormwater and increase access to nature in underserved neighborhoods.

Diverse interests, working together, have shown what’s possible.

In 2017, developer Mark Grey of Stephen C. Grey & Associates wanted to know how his project at the base of Seattle’s Aurora Bridge could help endangered salmon by filtering the toxic water running off the bridge and directly into Lake Union.

The bridge runoff “looked like a cup of coffee that’s been sitting around for five days, dark and sludgy,” Hilton said. Testing showed high levels of zinc, copper, lead and other pollutants that contribute to the decline of endangered salmon, orca and other wildlife.

The Conservancy collaborated with Grey, other nonprofits including Clean Lake Union and Salmon Safe, and state and local agencies to navigate a complex permitting process for swales and rain gardens that will eventually capture and clean more than 2 million gallons of bridge runoff annually.

Today, water flowing through first phase of the project, completed in 2018, is nearly clear, and pollutants have been reduced to safe levels. People living and working in the densely populated neighborhood can also enjoy the added green space, which helps boost activity levels and reduce stress. More gardens along the Burke Gilman trail will be complete in June, thanks in part to an additional $500,000 in state funding we helped secure.

In South Puget Sound, another project is not only cleaning stormwater runoff but also providing nutritious food and a connection to home.

In 2017, we began a partnership with World Relief Seattle to transform an unused church parking lot in Kent into a food garden where immigrants and refugees now grow produce that isn’t always accessible in their new surroundings. Cisterns provide most of the irrigation water, and rain gardens collect the remaining stormwater running off the hillside.

“The Kent Hillside Parking Plots projects demonstrates the value of community-led decision making and projects with multiple benefits for communities. The project is both a fantastic example of using nature to clean water, and it meets a true need identified and led by community.

Volunteers came out to build a community garden in Kent, Washington. Photo by Hannah Letinich.

Moving Forward, Together

Looking ahead, our state faces enormous challenges from climate change. We are all facing this crisis together and, without strong interventions, the health of our forests and waters will continue to decline, and with them, human health and well-being.

Whether in cities, forests or floodplains, the Conservancy’s partnerships are making landscapes more climate resilient and helping communities mitigate changes that are already apparent, such as more intense wildfires and floods.

We’re also helping to build and sustain one of the largest and most diverse advocacy coalitions in state history. Through the 2018 ballot Initiative 1631 to boldy advance climate policy, we helped welcome many voices to the table. An inclusive approach is shifting the dialog around climate change, and environmental equity and social justice must be part of broad-scale solutions. Our combined voices created a powerful force that is here to stay.

Only diverse interests working together can achieve the large-scale change needed. With 60 years of practice building coalitions, the Conservancy is ready to lead in the fight for a sustainable future, says State Director Mike Stevens.

“There’s a lot of value in the Conservancy’s history of bringing different kinds of people together to work on common-sense solutions,” Stevens said. “We are in a position to work across political differences, across geographic differences, to build coalitions and generate solutions.”

Banner photo by Jeff Marsh.

Water 100 Project Inspires Solutions for Puget Sound

A new initiative is driving to align this incredible pool of talent and ingenuity to tackle one of the most pressing challenges facing our region – how to address the threats of pollution, development and climate change to the body of water that defines this region, Puget Sound itself.

“None of us can solve the challenges of Puget Sound on our own,” says Jessie Israel, our Puget Sound Conservation Director. Through the Water 100 Project, an initiative of The Nature Conservancy and the Puget Sound Partnership, we’re creating a movement that brings together the Puget Sound business, government, NGO and scientific communities to identify, assess, fund, and implement the 100 most substantive solutions for improving our region’s water.