Local and national partners work together to produce adetailed toolkit that support a healthy urban tree canopy in Central Puget Sound – and a model that regions around the country can replicate.

Considering Climate for a Healthy Urban Tree Canopy

New Tools For Urban Trees

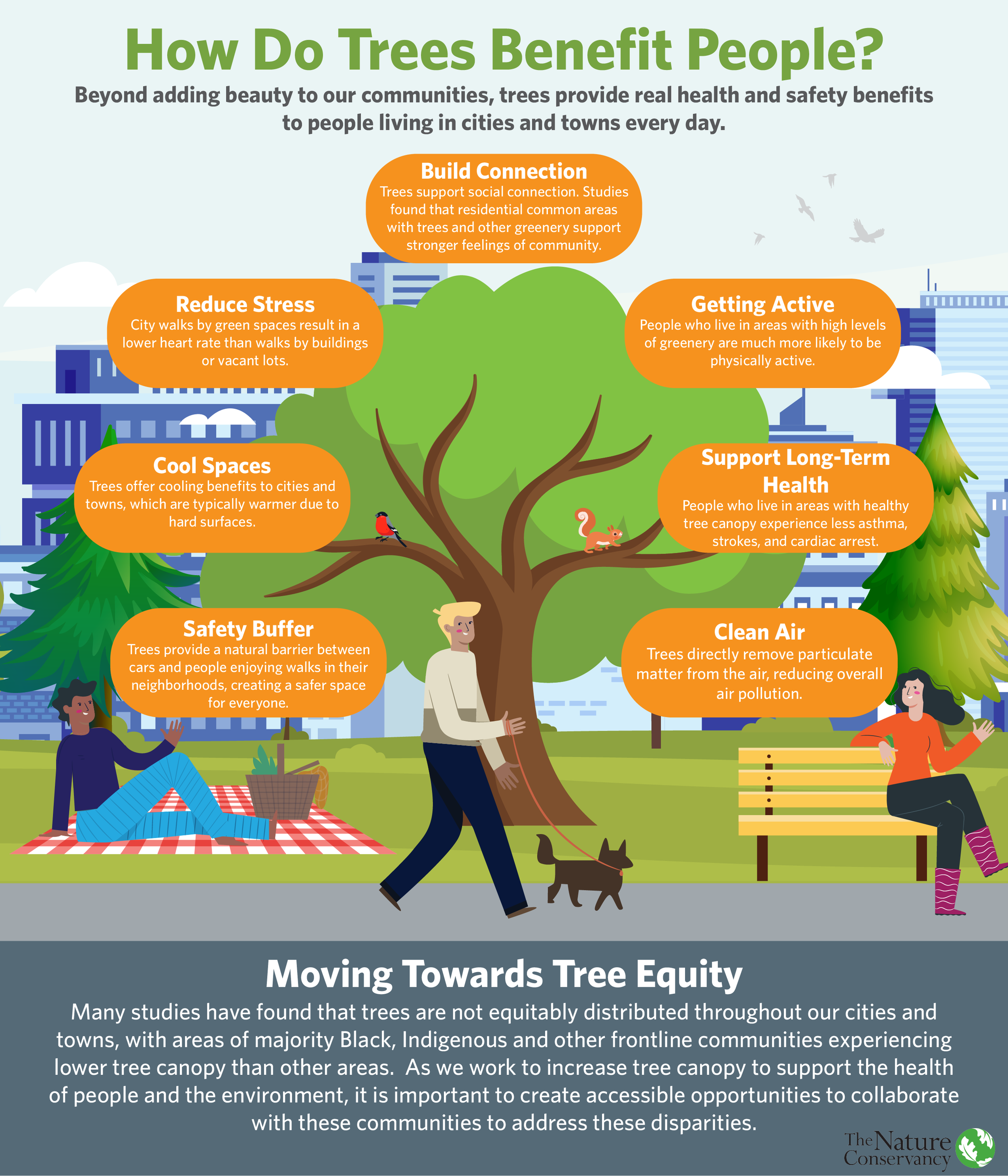

Health Benefits of Trees

City trees bring joy and other benefits

The Nature Conservancy has collaborated with partners throughout the Puget Sound region to support our urban tree canopy through planting, preserving and maintaining trees at residences, parks, schools and restoration sites. These projects are an opportunity to contribute to the health and resiliency of communities.

Trees are rooting community in Rainier Beach

October was for tree planting all around Puget Sound

You can be a voice for healthy urban trees

Let’s Plant Trees in Puget Sound

Rooted in Puget Sound: Our Winners Share How Trees Inspire

How to Care For Your Trees

In a Re-imagined Parking Lot, Trees Are Not Just Trees

Grandmother Ponderosa

Trees Are Where the Heart Is

Growing Pains among Sycamore Sentinels

Evergreen scents and childlike wonder

A seed to spark imagination

What remains

Art by Suze Woolf

Essay by Lorena Williams

#4 Mountaineer Creek Char

Year Painted: 2013

Likely Species: Unknown

Location 47.5366857135° -120.8136076969°

Elevation: 3,400’

Place Name: Washington CascadesFire: Icicle Creek Fire, 2001

What remains for news cameras is woodsmoke, ashpits so deep firefighters disappear to their waists, soot so gritty it clogs one’s pores to where no amount of scrubbing can remove it. Atop the hydrophobic ash layer rest yellowed pine needles that fell after the fire cooled. Also, frogs bloated and crispy, squirrels scorched as though on a spit for far too long—all the animals who cannot outrun the flames.

A trained firefighter sees much more than these surface observations. For experts, what remains is often enough to determine the fire’s point of origin, the factors of ignition, and the fire patterns that ensued.

Next time you hike into a fresh burn, start by looking at rocks. The side exposed to flames may show evidence of sooting or staining. In a more intense fire, this same side of the rock is pitted with small craters where the heat has spalled, or exfoliated, weak fragments. While you’re looking down, notice the white ash, where materials burned hottest and combusted more completely. In cooler, less intense sections of the fire, you may notice grass stalks that have been burned completely off at the base and have fallen (a tiny timberrrr!) toward the advancing flames.

At waist- or possibly eye-level, notice any remaining leaves on oak or chaparral—they curl inwards and always towards the advancing heat. Look closer at the plant now, at its smaller branches left partially burned. On the lee side, where low-intensity flames burned underneath, twig ends may be cupped in a concave shape. On the contrary, twig tips exposed to direct, oncoming flames will be rounded and burned off.

Take a breath and take in the larger scene. Fire moves in micro patterns, changing inch by inch, but it also moves on a macro scale. Do the trees around you all show black char on one side but not the other? The char side was exposed to the advancing front while the back was protected. Likewise, you might see an angle of char in the tree tops where some foliage remains. Fire climbs the tree on the windward side and bursts out the top on the lee side, leaving a diagonal wedge of untouched foliage. (The low end of the angle of char will coincide with the charred side of the tree.)

It's time to climb into your helicopter and tell me what you notice about the fire’s shape. Is it long and skinny—a U-shape? Well then, it’s likely wind driven. Is it more of a V-shape, moving from the base of a slope to the top? I’m willing to bet that the bottom of the V is where you’ll find the point of origin.

What remains after fire is a thousand clues small as a blade of grass that speak to those who know what to listen for.