By Bunthay Cheam

For years, a neglected 2.6-acre green space in Shoreline has sat adjacent to Ballinger Homes, a low-income subsidized housing community. This neglect has led Ballinger Open Space to be filled with invasive weeds that include knotweed, Himalyan blackberry and English ivy.

A multi-pronged partnership aims to restore the health of this riparian area by turning back the clock.

Volunteers from the community restore Ballinger Open Space. © Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

The Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust, City Forest Credits, the City of Shoreline and residents of the Shoreline community have come together to restore Ballinger Open Space to its natural condition and make it more appealing for public access.

This public green space access is especially important because of the high number of youth and families that live in the area, particularly the adjacent Ballinger Homes, and the opportunity to mitigate air pollution from nearby highways. Ballinger Homes sits at the nexus of Interstate 5 and State Highway 104 in the northeast corner of Shoreline. In addition, restoring the green space, removing invasive weeks and planting coniferous trees will help slow erosion and flooding, effects of high water flow during heavy rains.

According to data provided by King County Housing Authority, Ballinger Homes has 131 households, with 40% of the residents under 18 years of age. 72% of the of the residents are non-white. Languages spoken in these homes include Spanish, Vietnamese, Russian, Arabic, Ukrainian and Korean. In contrast, the city of Shoreline overall is 70% white according to 2019 Census estimates, and persons under the age of 18 were 19% of city residents.

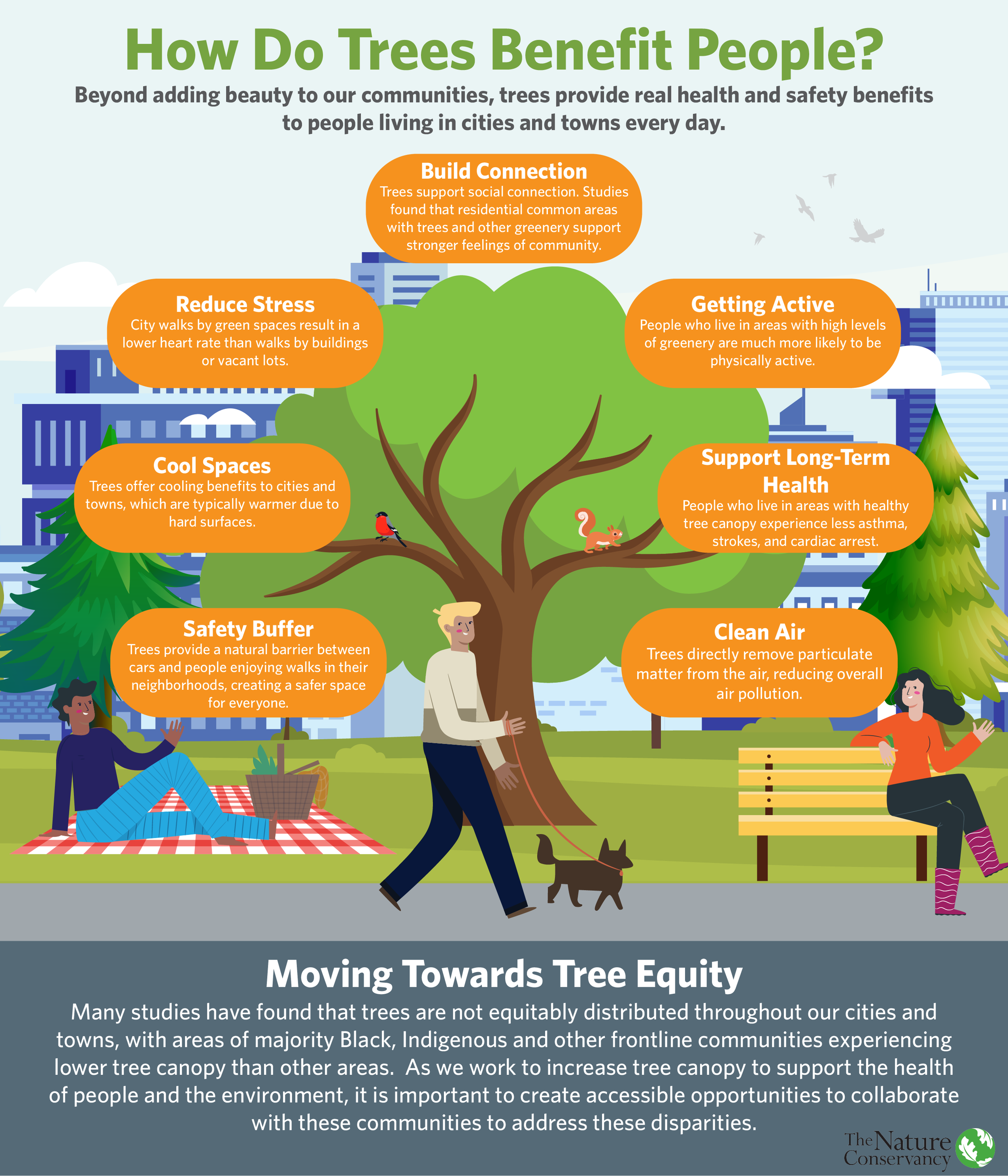

In describing the project, Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust points to the importance of green spaces in underserved areas. “Urban forests improve social and environmental equity when planted or preserved in disadvantaged communities – they store carbon, provide shading, cooling, and energy savings, improve air quality, reduce stormwater runoff, stabilize slopes, and improve human health and happiness,”

Ballinger Homes neighborhood is immediately adjacent to Ballinger Open Space, where neighborhood volunteers plant trees. © Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

This project looks different than other Mountains to Sound Greenway projects, centering community benefits that are not directly tied to Chinook salmon. This means that the typical Mountains to Sound Greenway funding mechanisms were not fully available. This led Mackenzie Dolstad, Stewardship Program Senior Manager of the restoration project, to get creative.

“We started working with an organization called City Forest Credits that was looking to find opportunities to take and value urban forest restoration and demonstrate the benefits that it has to communities and try to look at a way to generate local carbon credits out of that model, so that people could support local restoration efforts that bring local benefits to bear and we realized that this might be an opportunity to pilot and test that model a little bit.”

This also led to other partnerships and collaborations – including different funding opportunities, like the King County Flood Reduction Fund. “We started… thinking about it as a restoration in an urban area that can help with stormwater management benefits,” said Dolstad.

A partnership with Carter Subaru’s Shoreline location called “On the Road to Carbon Neutral” supports planting of native trees through test drives. Through this partnership, Carter Subaru has also agreed to provide up to $5,000 in cash match.

As of January, the project had engaged over 100 volunteers from AmeriCorps and planted more than 1,200 native plants, including 1,100 trees such as Douglas fir, Sitka spruce, Western red cedar, Cascara, Red Alder, Black cottonwood, and Pacific willow through volunteer events.

While COVID-19 brought work to a pause, project leaders hope to continue connecting with the community through a series of outreach campaigns that include partnerships with local Forest Stewards, a local grade school, scout troops and religious institutions to sustain Ballinger Open Space and keep it in its natural form for years to come.

“At the heart of our mission is the belief that when we're connected with nature, our lives are better and our actions are our mechanism that drive a lot of what we do.” said Mackenzie Dolstad, Stewardship Program Senior Manager of the restoration project. “And part of that is building connections with communities.”

The Nature Conservancy in Washington provides funding support to this project as part of our Planting Trees for Thriving Communities project.

Bunthay Cheam is a Khmer American refugee born in Khao I Dang, a refugee camp on the Cambodia-Thai border. He enjoys receiving, holding, and sharing stories.

Banner photo © Hannah Letinich