By Darcy Batura, Forest Partnerships Manager

For centuries, the people of Kittitas County have depended on forests and water. This land was inhabited by the Kittitas band of the Yakama Tribe, who used the word Tle-el-Lum, meaning swift water. An adaptation of that word was eventually used to name the city of Cle Elum, where our TNC field office is located.

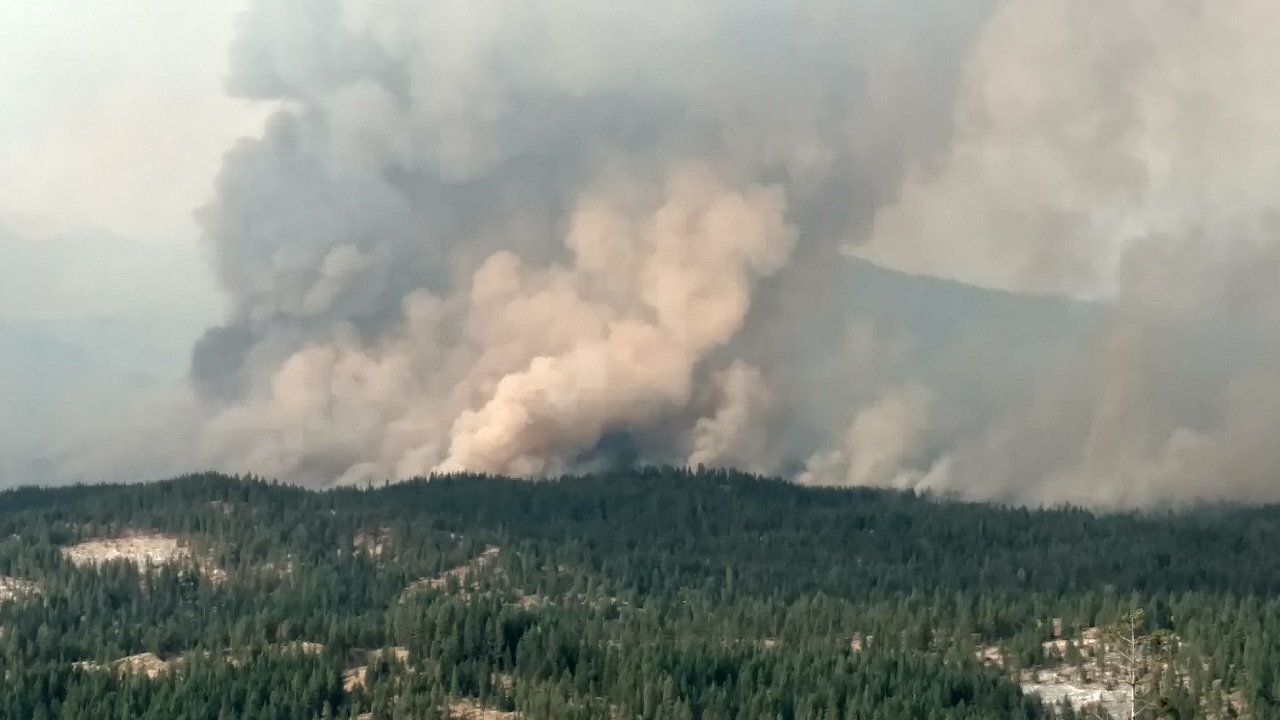

Centuries later, as we work to develop natural resource-based solutions to regional problems, in Kittitas County, forest and water remain the central focus. Our forests are under increasing stress due to a century of forest fire suppression and a changing climate. In 2014, The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Forest Service completed a peer-reviewed scientific analysis of the forest restoration needs in eastern Washington. The analysis found that 2.7 million acres required some form of restoration to return to a natural range of variation, improve habitat and reduce the risk of uncharacteristic wildfire, disease or insect outbreaks. Approximately 700,000 acres of the area needing treatment is found on the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest.

In Central Washington, our work is mostly focused on forest health and we need to do a better job of expanding our implementation of holistic ecological restoration at a scale to meet the restoration need. The same wildfire and climate change issues that are impacting forest health are also impacting water quantity and quality, directly affecting federally listed salmon, communities and small farms throughout central Washington.

In a time when resources and capacity are tight, which is more important: the forests or the water? Gifford Pinchot answered that question this way: “The relationship between forests and rivers is like father and son. No father, no son.” We cannot choose between them—they are fundamentally connected.

What exactly do forests have to do with water? Healthy forests capture and hold snow in the winter, then absorb rain and snow like an enormous sponge in the spring, acting as a natural filter, replenishing underground aquifers and slowing the flow of water as it moves downhill. In addition to providing water for communities and agriculture, water flowing from our forests supports valuable ecological services: wetlands, meadows, lakes and streams—and all the aquatic communities that depend on those environments.

Forests are the most effective land cover for maintenance of water quality. The ability of forests to aid in the filtration of water doesn’t only provide benefits to our health and the health of an ecosystem, but also to our pocketbooks. Forest cover has been directly linked to drinking water treatment costs. So the more forest in a watershed, the lower the cost to treat that water. Forests provide these benefits by filtering sediments and other pollutants from the water in the soil before it reaches a stream, lake or river.

But wait, climate issues are huge! What can we do that is meaningful? A lot, actually!

Within the Central Cascades, the challenges facing our forested ecosystems from past management and future climate change have prompted a wide-scale shift in land management to focus on ecological restoration. Solutions to these issues are at a scale that transcends ownership boundaries. Our work on cross-boundary pilots, like the Manastash Taneum Resilient Landscapes Project, are developing tangible ways that we can protect both forests and water in an era of climate change.

The objective is to “restore the resiliency of forest and aquatic ecosystems in order to continue providing critical fish and wildlife habitat and ecosystem services while reducing the risk of catastrophic fire to local communities in the face of a warming climate.” The best available science is used to balance ecological objectives with economic viability, produce commercial timber products where possible and maintain sustainable recreational opportunities.

The work to address restoration needs across 2.7 million acres can sometimes feel daunting. However, these pilot projects are charting the path toward a new model for restoration that will benefit both the forest and water resources for generations.

These steps are also good for jobs and the economy. One study has shown that every million dollars spent on restoration activities generates 12 to 28 jobs. Restoration is good for the environment, it’s good for the economy and it’s good for local communities where jobs might be lacking.

Few forces are more important than water in shaping the human condition. Water is a central organizer of ecosystems; water shapes the physical landscape and governs its vegetation, laying the very basis for human life, civilization and the communities that we call home.

If you’ve spent time camping next to a stream or hiking alongside your favorite river, you understand that our forested watersheds are part of our identity and are a valuable legacy that cannot take for granted. Let’s face it: Forests and trees are an undeniable combination. They are two peas in a pod; they are like peanut butter and Nutella: The significance of their union is as undeniable as the force of love.