by Grace Lee Kang

This is part two of a two-part series on important work happening at the Port Susan Bay Preserve; you can read part one here.

Rebuilding an estuary, one of the most productive ecosystems on earth, takes dedication.

Estuaries, the marshy areas that exist between where the land meets the sea, provide productive feeding grounds, refuge from predators, and are an important transition zone for young salmon as they physiologically acclimate from fresh to salt water. Estuarine marshes are critical habitat—without them, Chinook salmon in Puget Sound will not recover.

Port Susan Bay Preserve. Photo: Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife

In order for salmon to adapt to climate change, we need to protect and restore the many habitats necessary to complete their life cycle. Last winter’s floods highlighted the vulnerability of upstream spawning habitat, areas where salmon lay their eggs, to climate change. Large flood events with swift water can scour the river bottom leading to low survival rates. Estuaries are another climate-vulnerable salmon habitat.

Illustration by Erica Simek Sloniker / The Nature Conservancy.

In Puget Sound, there is an extreme deficit of functioning estuary habitat that is severely impacting not just salmon, but a host of other wildlife and the human communities that rely on them. To put it into perspective: the Skagit, Snohomish, and Stillaguamish Deltas draining into the Whidbey Basin account for ~70% of Puget Sound’s historic delta habitat, yet only 31% of that acreage remains. With climate change, these remnant marshes are further squeezed between rising sea levels and the land.

The original estuary footprint in the Whidbey Basin that was lost due to land use changes over the last century, and that is in the process of being recovered. Map: Erica Sloniker\TNC.

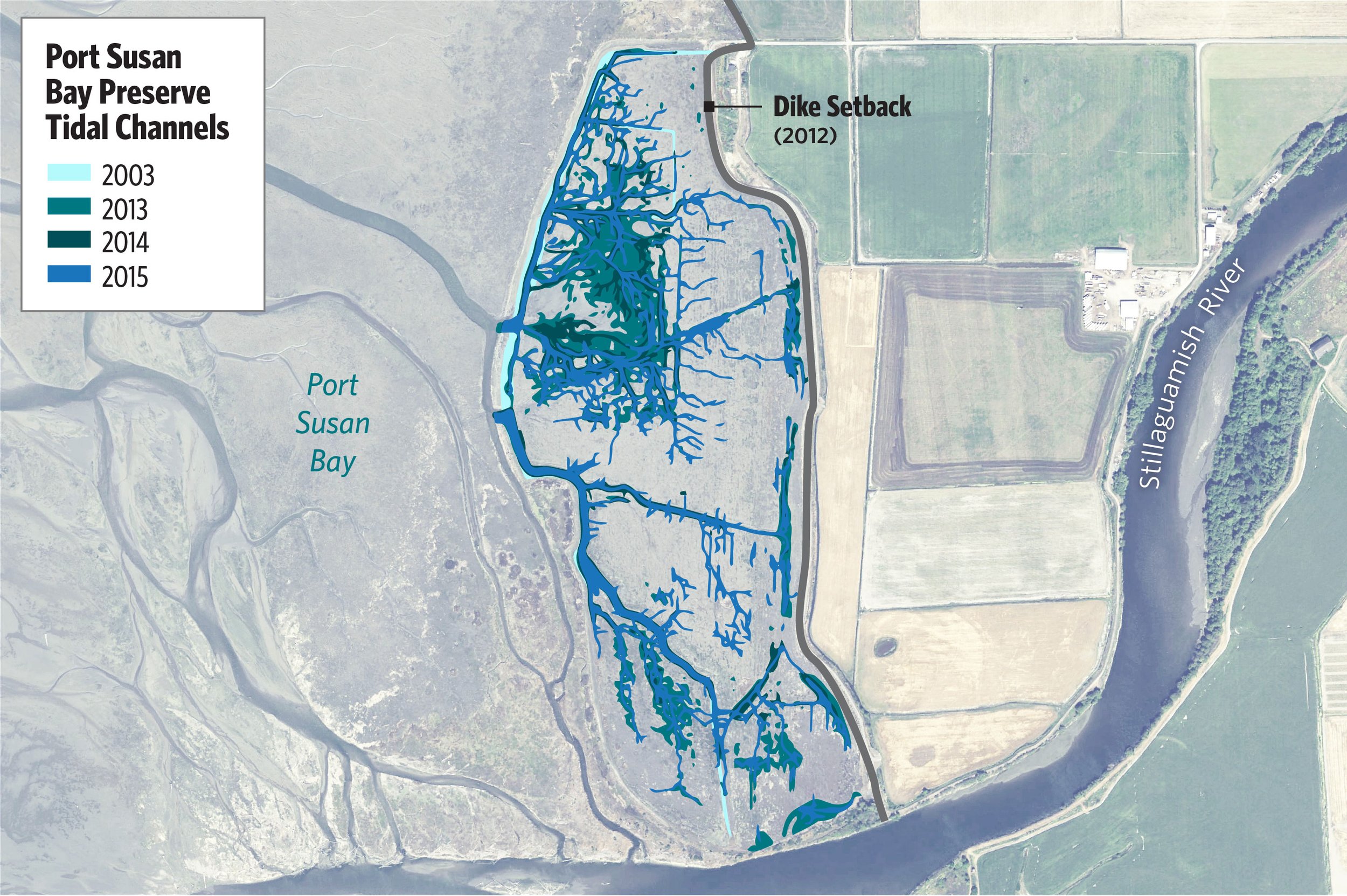

Alongside the work of local partners also working in the area, TNC has been working to address this issue directly through estuary restoration at the Port Susan Bay Preserve. In 2012, the first large-scale restoration phase removed 7,000 feet of dike that had separated the 150-acre marsh from the rest of Port Susan Bay since the 1950s. Ten years of ongoing restoration efforts, tides and data collection later, some key barriers still remain. For instance, the stalled development of small channels within the marsh and a lack of direct connection between the restoration site and the Stillaguamish River mean fish struggle to access most channels in order to feed and grow.

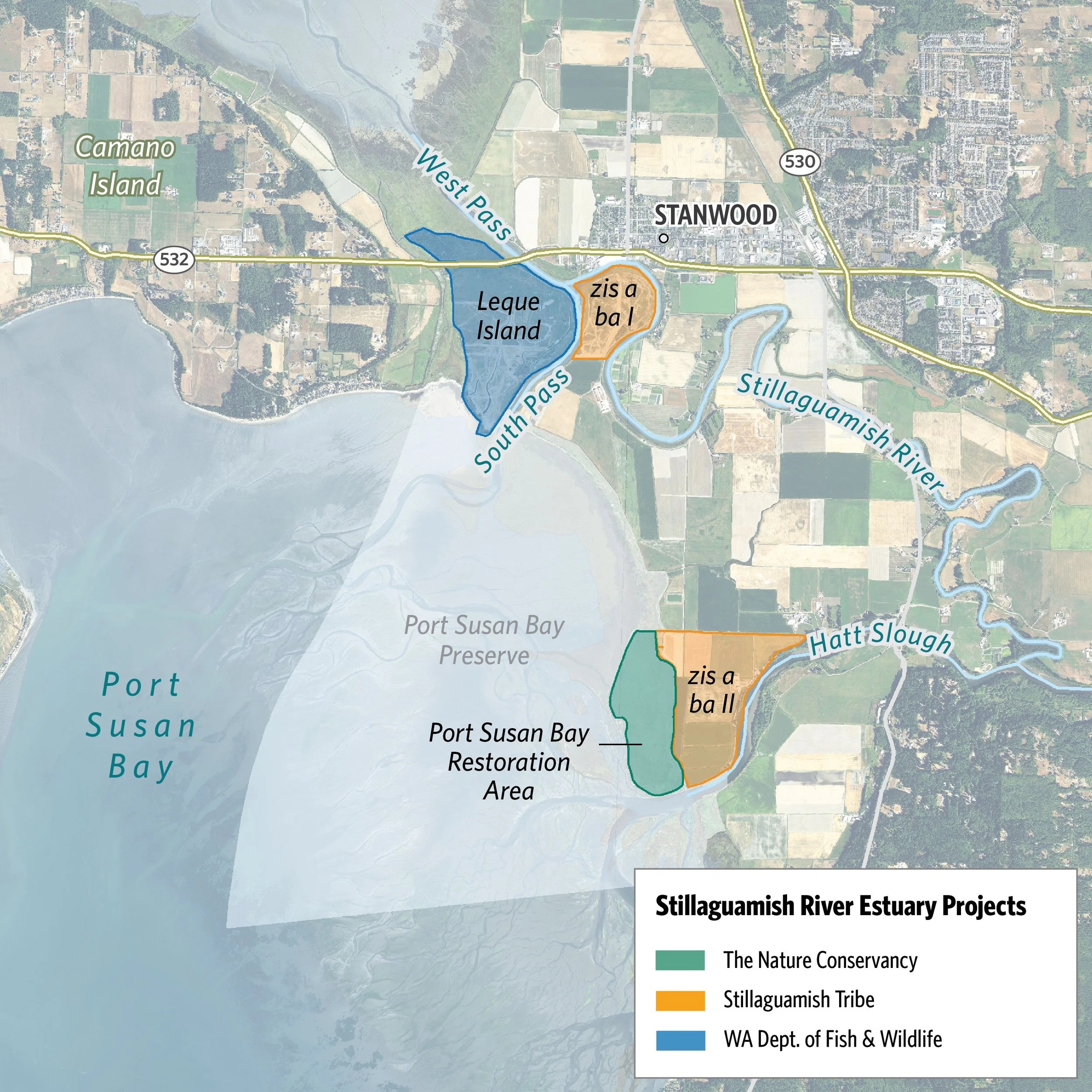

And yet Port Susan Bay Preserve is just one part of a wider network of restoration and land management projects across Puget Sound, often led by Tribal Nations. Collaborating with local partners has been a priority to open up new possibilities with even larger-scale restoration. Like with the Stillaguamish Tribe’s 248-acre parcel adjacent to Port Susan Bay Preserve—an exciting opportunity to see a restoration design implemented in synergy with TNC’s restoration efforts to date, which will further create opportunities for connectivity across the river, marshes, and the bay.

As seen through other estuarine restoration projects along the west coast, as well as river restoration projects like those developed by the Skagit River System Cooperative, recovering diverse, functional, and connected channel systems ultimately builds a stronger, more resilient landscape.

Stillaguamish River estuary restoration projects. Map: Erica Sloniker\TNC.

A Collaboration, Innovation and Learning Network powered by years of partnership and research

Together with local research partners, TNC has been contributing new data and learning to the research landscape over the past decade. The land and restoration projects serve as a key foundation, enabling research teams to formulate hypotheses and monitor ecosystem response.

By monitoring channel development and mapping out the length, width, and depth of channels within the restoration zone, the Skagit River System Cooperative (SRSC) gained a better understanding of the rate of recovery. Researchers at Western Washington University measured sediment accretion rates to understand how well freshwater and sediment are distributed across the delta by the river, and therefore how well different areas of the delta’s marsh ecosystem are keeping up with sea level rise. Since 2012, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) has also run annual vegetation and salinity monitoring crews across the Stillaguamish delta to develop a long term data set indicative of marsh resilience. And recently, TNC has teamed up with SRSC to monitor fish populations throughout the Stillaguamish delta, knitting together a suite of restoration projects to support delta-wide learning.

Researchers at Port Susan Bay Preserve. Photo: Emily Howe/TNC.

The more robust and comprehensive the data, the more we can uncover linkages between river hydrology, restoration design, and ecosystem responses—including critical factors that indicate the long-term resilience of healthy marsh ecosystems, or the ability of the delta’s restoration projects to support salmon growth and survival.

With the thousands of hours of research and data collected over the past 10 years, these areas of study have driven the current adaptive management approach to restoration planning, where techniques and concepts are tested in an environment that’s continually shifting from climate change. And now we can use past data combined with current data and modeling to look forward to a brighter future—one where we might foster a healthier and more resilient habitat for Chinook salmon.

Researchers at Port Susan Bay Preserve. Photo: Emily Howe/TNC.

Looking ahead, the latest research continues to explore and test innovative ways of thinking. In collaboration with the Skagit River System Cooperative team, TNC scientists are considering an important question: how can a restoration project influence neighboring areas? Can increasing channel connectivity in a critical location enhance Chinook distribution across the entire estuary? Can certain channel connections influence habitat conditions enough to ultimately affect the growth potential and survival of young fish moving through the system? By better understanding the biology of the fish and how they interact with the environment, we can adapt restoration work to address the evolving impact of climate change with greater precision.

As part of a network of restoration and land management projects, each one is like a collaborative, learning and innovation space able share knowledge from the other and in theory, recovery could cascade across the whole of the delta, beyond the borders of the preserve.

Advancing conservation is a large-scale, ongoing collaborative effort between TNC scientists and fellow partners. From preserve managers and project engineers to community members and tribal scientists—throughout the restoration process, a focus on collective success to meet not just conservation outcomes, but the goals of local communities, partners, and ecosystems will drive success that lasts.

Top banner image: Researchers seine fishing at Port Susan Bay. Photo: Emily Howe\TNC.