The way of connection is revealed by water—snowy summits melting, forging rivers, winding streams and cutting wetlands to spill over a salty edge. Join Dr. Emily Howe, Ecologist of Aquatic Environments for TNC Washington, as she poetically details the interconnectedness of a watershed.

Watch the Video: A Day in the Life

5 Nature Conservancy Preserves in Washington You Can Visit Anytime

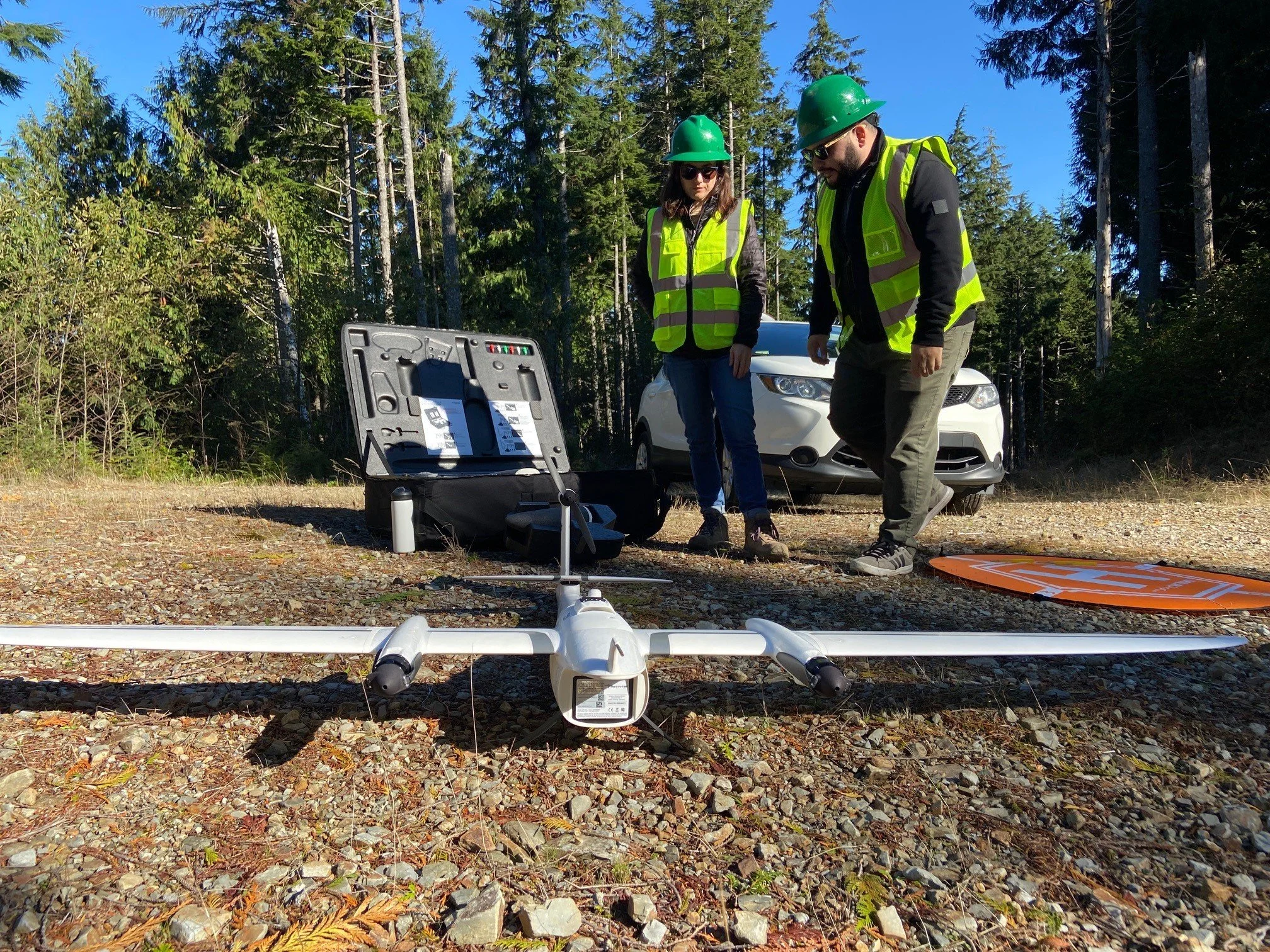

Taking Flight: How Drones Amplify Conservation Efforts

Drones have emerged as a groundbreaking tool extending our reach beyond the limits of human exploration. While many are familiar with seeing the possibilities in adventure photography or package delivery, the use of drones in conservation has become increasingly creative for those both out in the field and in the lab.

Summer Science Interns Find Connection in Conservation

When Restoration Gets Explosive

Using dynamite for restoration may seem like a paradox, but at TNC’s Port Susan Bay Preserve, we explored dynamite as a way to create estuary channels. The inspiration behind this method was to see if explosives could reduce the ecological impact of channel creation in comparison to using heavy machinery.

Port Susan Bay Preserve: Where have all the Chinook gone? (Part 2)

Summertime Science

Two students from The University of Washington completed science internships with The Nature Conservancy over the summer. Stephanie Passantino and Eileen Arata worked with us on several projects including Ellsworth Preserve camera trap and tree reproduction research projects, an eastern forests literature review, Greening Research in Tacoma, and Port Susan Bay Preserve restoration.

Join us as both Eileen and Stephanie tell us about their experiences this summer in the field!

Where the Water Meets the Sea

KCTS9-Crosscut interviews Dr. Emily Howe, Aquatic Ecologist at The Nature Conservancy for their “Human Elements” series where Emily talks about her personal connection to marshes and how she is working to restore these unique—and messy—ecosystems.

A Piece of History Gone But Not Forgotten

Written and filmed by Joelene Boyd, Puget Sound Stewardship Coordinator

Recently, a piece of history was removed from the landscape at Port Susan Bay Preserve. The house that had been a part of the landscape for over 60 years is now gone. Homesteader, Menno H. Groeneveld bought the house for a bargain price as the Interstate freeway was expanding through Seattle and moved it to the property so the story goes.

Groeneveld was an ambitious man who inherited a portion of the tidelands of Port Susan Bay back in the 1950’s. Initially he thought his inheritance was agriculture land until, upon his arrival from the mid-west, he realized it was not. However, he didn’t let that dampen his dreams and set to work building a dike around 160 acres so that he could pursue his calling - farming.

Every time I think of all of the options that someone in his shoes could have done I’m struck by the pure determination he must have had to embark on building a dike around then mud and estuary and start a farming operation.

In 2012, The Nature Conservancy removed this outer dike and restored 150 acres to estuary habitat to support juvenile Chinook Salmon, water birds and other estuary dependent fish and wildlife species.

As I watched the house come down I knew it was the right thing for conservation and giving this piece of land back to the natural world. But I was also sad that this piece of history was being erased from the landscape.

What's next for this area? In the immediate future I will plant some annual grass to keep the weeds at bay but longer term it would be great to restore native trees and shrubs and install a kiosk of sorts for people to come, congregate and learn about Port Susan Bay and The Nature Conservancy's amazing work in restoring and protecting this special place.

The house is now gone but the story of this man and his resolve will stay with me for a long time to come.

Learn more our Port Susan Bay

Jared Rivera: A Doris Duke Conservation Scholar

Written & Photographed by Kat Morgan, Puget Sound Community Partnerships Manager

On a chilly morning in the North Sound, 20 semi-sleep deprived undergraduates from across the country (there were some fireworks and late nights at their campsite the previous night) stood in our Mount Vernon office parking lot learning about who The Nature Conservancy is, and our work in Washington, particularly Puget Sound. These were the 2016 cohort of Doris Duke Conservation Scholars, a program sponsored by the University of Washington. This two year program is designed to help foster and ultimately increase diversity in the conservation workforce. These were the first-year students – freshmen and sophomores - participating in this 8-week field program in Washington. They visited conservation projects and professionals around Puget Sound, learned about current conservation needs and issues, and about the people doing this work. We toured our Mount Vernon office to give them a sense of what it might be like to work for The Nature Conservancy, and then headed to one of our flagship project sites – Port Susan Bay. Most students knew the Conservancy purchased and conserved lands. Only one knew that we actively managed those lands, or that we supported and implemented large-scale, landscape changing projects beyond our own ownership.

After hearing about the needs for restoring floodplain systems across Puget Sound, they had lots of questions about how you work with communities to do this work. What kinds of outreach were required, and how did you go about it? We talked about how each community has different needs, and you approach each community differently depending on the circumstances and people involved. They nodded their heads when we talked about the similarities – in each community, you ask questions and listen. You listen a lot - to understand what is needed, what is important to the people who live in that place, and you work together to find space for all those needs in a project.

We toured the Port Susan Bay restoration project site at low tide, when all the restored tidal channels and estuarine marsh were visible and visited the flood return structure, installed to address local flood issues as part of the project. Migrating shorebirds moved around the shallow pools left by the tide. The students marveled at the remoteness of the site, even though houses are visible all around, and the subtle energy, where at a distance everything appears very still, but when you get closer, you see song and shore birds flitting round the marsh, rushes moving in the breeze, and raptors on the wing looking for lunch.

As we wrapped up the tour, we turned the tables and I asked questions of this group of future conservation professionals. Jared Rivera is one of the Doris Duke scholars. He studies environmental engineering at UCLA. As a Native American, Jared is very interested in the intersection of social justice and conservation, in making sure Native American communities are engaged in problem-solving and decision-making around natural resources. Jared appreciates the interdisciplinary teams the Conservancy puts together to tackle conservation problems, and one day, when he finishes his environmental engineering degree, is interested in a seat at the table.

PROFILE

Name: Jared Rivera

Hometown: Murrieta, Southern California. Going to college at UCLA.

Murrieta is located in the center of the Los Angeles San Diego mega region of 20 Million people. After interstate 15 was built in the 1980’s, suburban developments started being constructed. Today, Murrieta is known as a commuter town and the largest employer is the school. I know this area though. I have family on Camano Island. It’s really interesting to hear about your projects here.

Childhood Dream/what did you want to be when you grow up?:

Until I was 17, I wanted to join the Marines. Then my ideas changed. I had an AP bio teacher who taught us about ecology and took us on field trips to the Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies. I was fascinated by a project they were working on of sustainable algae fields for biomass production. I applied for a student study program at the Wrigley Institute and was accepted.

What about our work do you find most inspiring? What is most surprising?

The Levees at the Port Susan Project. The fact your conservation organization isn’t afraid to make changes to the environment, and to build infrastructure if it will help you accomplish your goals. Humans have already meddled with nature to mess it up. The only way to fix it is to keep meddling.

What would you most like to see The Nature Conservancy work on that you didn’t hear about today?

I would like to see The Nature Conservancy become more involved in social justice issues. Particularly as a Native American, I would like to see more indigenous communities included in the problem-solving and decisions around our natural resources.

What would make you want to work for us?

I am really excited about the interdisciplinary approach you described bringing experts from all different fields together to problem-solve, to have a seat at the table, particularly involving social justice issues.

Purple Martins: New Residents at Port Susan Bay

Written Joelene Boyd, Puget Sound Stewardship Coordinator

Photographed by Julie Morse, Senior Ecologist & Skagit Audubon Group

Thanks to dedicated volunteers we now have new residents at Port Susan Bay – Purple Martins. We are really excited by this because it is the first time (at least in recent history) that Purple Martins have been seen at Port Susan Bay (PSB) and it’s all thanks to volunteers.

In mid-February volunteers came out and installed bird houses then later in May another group of volunteers from the Skagit Audubon installed some more.

I asked Mark Perry, of Skagit Audubon, some questions about Purple Martins and this project.

Why it is important to install purple martin boxes?

Purple Martins while not endangered suffer from habitat loss along the West Coast. They are "cavity nesters"...building nests in holes. Free standing Snags along bodies of water are perfect sites. On the East Coast humans have provided nesting sites since the early colonial days and the birds have adapted, accept living in close proximity and thrive. Along the West Coast the practice of providing replacement man made housing has not been as prevalent.

Is there a specific conservation target or goal in mind?

Our conservation target is simply to expand the number of nesting sites and thereby hoping to attract more nesting pairs. Our friends to the north in British Columbia have a very successful and extensive effort. Their program has grown from just a few boxes, sites and less than 100 birds to more than 50 sites, over a thousand nesting boxes and a survey population of 4500+ birds.

Why Port Susan Bay?

In Skagit, county there are only two identified Martin nesting sites. PSB offers almost perfect natural habit...wide open marsh land near body of water but lacks tree snags. Nesting boxes were removed when the dikes were removed/relocated. By utilizing the existing left over pilings and providing 3 additional nesting poles (like a snag) we hope to attract a new population of nesting pairs and reestablish a thriving colony. Martin's eat flying insects and are very social curious birds!

Why is the Skagit Audubon focusing efforts around the region to install these boxes?

Like most volunteer projects it takes a few interested and passionate folks to see a need, figure out ways to address the need and take action. Skagit Audubon has over 200 families as members, is focused on local conservation efforts and fortunately have some handy folks willing to get involved. Please check out our website www.skagitaudubon.org for more information about our chapter.

Where else can folks see these boxes?

36 boxes are up and a thriving colony exists at Ship Harbor near the Anacortes Ferry terminal. The site is easily viewed from the Ship Harbor interpretive trail.

11 boxes are up just north of the Padilla Bay interpretative center in Bayview.

9 boxes are up in English Boom.

We hope to add 30 more boxes by next season at Wiley Slough and yet to be determined sites.

Are they just birdhouses or do they have special dimensions that make purple martin houses?

A Martin Birdhouse is a bit unique. First the orientation is more horizontal than vertical. The entrance hole must be large enough for Martins but not too large to allow starlings or house sparrows to hijack the box. The box needs to be 12-15' off the ground. And since Martin's are colony nesters you need 5-7 boxes to attract them.

If someone wanted to help out in purple martin efforts what should they do/who should they contact?

If someone is just a bit handy and would like to build boxes I can share some simple plans via email. Please see the chapter President email found on the Skagit Audubon’s website skagitaudubon.org.

If folks notice Martin's already nesting at a "natural" site please let Skagit Audubon know. Or if you think there is a potential site where we could easily access and add nesting boxes that's good info too. (Using same skagitaudubon.org email).

If you would like to join our citizen science monitoring team please contact Skagit Audubon. And of course we welcome anyone who would like to join Skagit Audubon and become active members!

Thank you Mark and all of the volunteers who helped on this project!

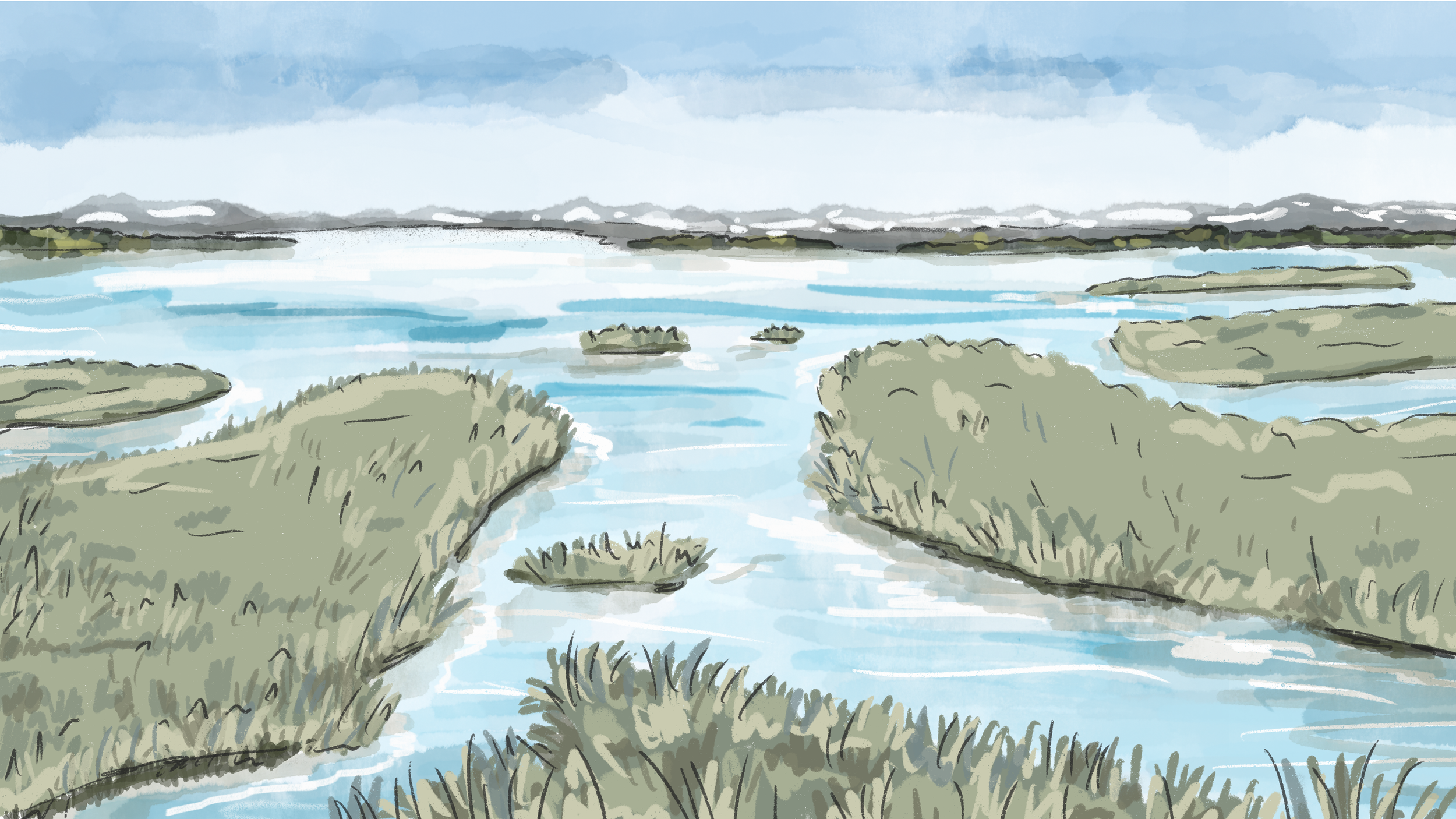

Rebuilding an Estuary, Designed by Nature

Written by Beth Geiger, Northwest Writer

Graphics by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

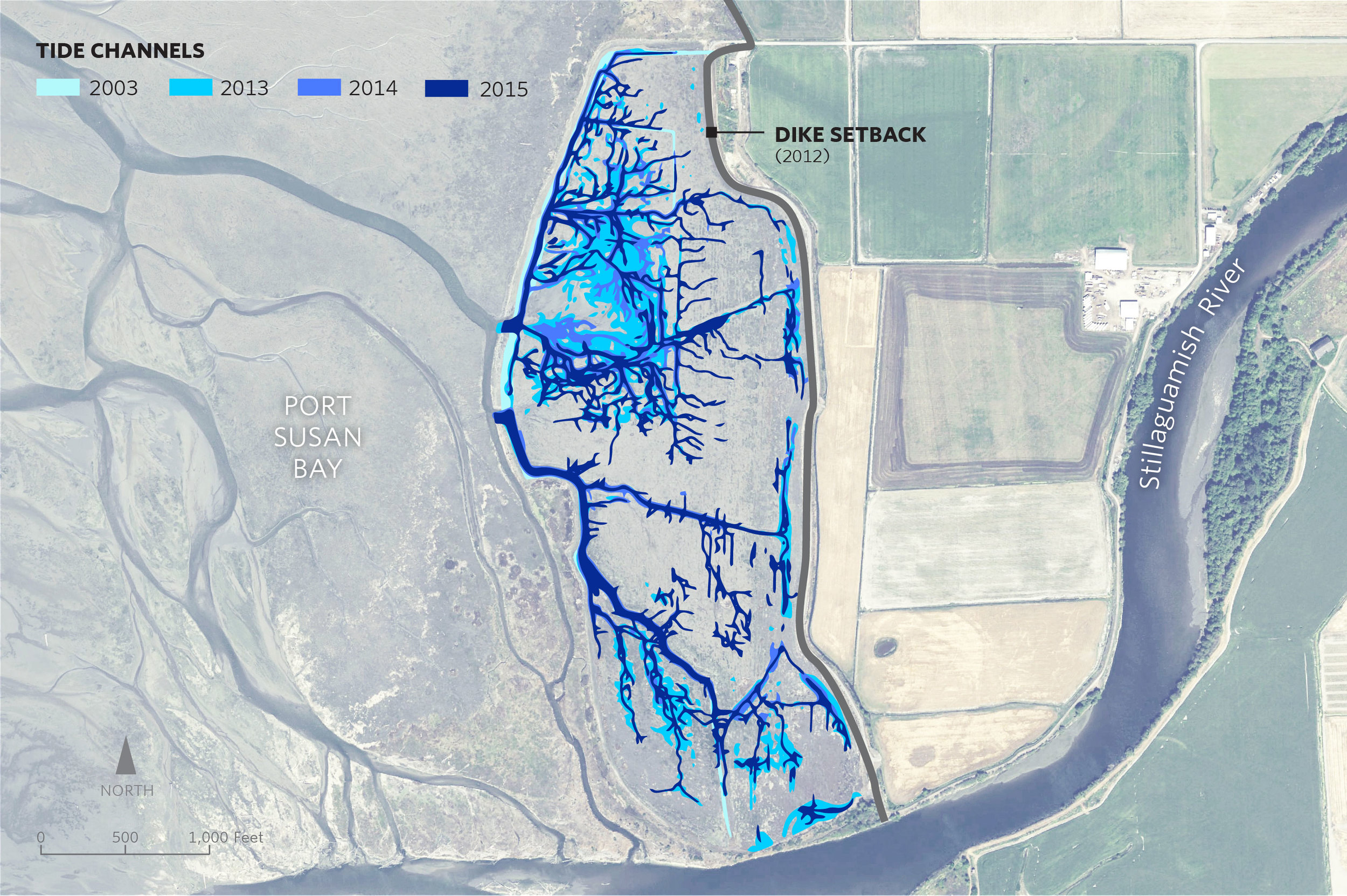

A dramatic change has taken place in a marsh in Port Susan Bay, near Stanwood, Washington. In just three years the total length of tidal channels naturally increased tenfold, from 2,300 to 23,000 meters.

Tidal channels are key to a well-functioning estuarine ecosystem. Channels increase habitat diversity, which in turn increases species diversity. Juvenile salmon use the channels, dabbling ducks use them, and invertebrates that provide food for other species use them.

Scientists like Roger Fuller, an ecosystems ecologist at Western Washington University, are chronicling the new tidal channels, along with other changes here. Fuller says the development of so many new channels is “a big surprise.”

Marsh Revival

The new channels started forming in 2012, after The Nature Conservancy removed 7,000 feet of dike that had separated the 150-acre marsh from the rest of Port Susan Bay since the 1950s. The dike removed had over time diverted Hatt Slough, the Stillaguamish River’s biggest distributary channel, south where it spills into Port Susan Bay. That dike had also cut the marsh off from its main source of fresh water and sediment.

With marsh, river, and Puget Sound connected again, natural processes took over. Critical estuary habitat quickly began to be rebuilt. A natural revival was underway.

The channels are a big part of this revival. “Channels build connections, creating the intimate links that tie the marsh, tide and river together,” Fuller explains. “They serve as the trade routes of the estuary, funneling water, sediment, fish, and the organic matter that fuels the entire estuarine food web back and forth between marsh and tidal flat.”

Sound Science

Supported by the Conservancy, Fuller and other scientists including Greg Hood with the Skagit River System Cooperative, and Eric Grossman, Christopher A. Curran and Isa Woo from the United States Geological Survey have been studying the channels and other ways that this estuary is recovering.

The researchers analyze before and after data, and compare the restoration area to a nearby reference marsh which has never been diked. They measure suspended sediment, water temperature, salinity, current, as well as topographic and ecological changes.

New tidal channels aren’t the only “before and after” they’ve seen. When the dikes were in place, the area inside them had been starved of its natural influx of sediment from the Stillaguamish River. The estuary had subsided until it was a meter lower than the surrounding tidelands in some places. It functioned more like a pond than a dynamic estuary. For example, there was no access or protected estuarine habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon transitioning from the Stillaguamish River into Puget Sound.

With the dike removed scientists have recorded a measurable rise in the height of the marsh. During those years the sediment delivered to PSB was unusually high in part due to the March 2014 Oso landslide. However, the data suggest that even if the marsh gets half as much sediment in future years, it may still rise fast enough to keep up with the rising sea level, estimated to be an average of about 24 inches by 2100.

Lessons from Nature

Fuller says that being surprised by nature here isn’t all that unexpected. “The one thing I knew before the restoration was that I would be surprised by the changes triggered by the restoration,” he says. “There's been so little research on restoration in northwest estuaries that I knew it would be really interesting to watch it unfold.”

The restoration project is part of the Port Susan Bay Preserve, which includes 4,122 acres of estuary that the Conservancy acquired in 2001. The science being conducted here reaches much further than the Preserve itself. Along with learning new lessons, we are applying scientific concepts and models honed under this and other Conservancy projects such as Fisher Slough.

Together, these projects demonstrate that carefully planned restoration can have complementary, not conflicting, benefits for people, salmon, farms, and wildlife. The Conservancy-led Floodplains by Design provides the partnerships and funding that ensure these lessons can extend to restoration projects all over Puget Sound.

As a result of diligent science and critical partnerships like this, we are learning how to make Puget Sound more resilient as climate changes, and sea level rises.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK IN PUGET SOUND

LEARN HOW CLIMATE CHANGE WILL AFFECT THE REGION AND WHAT WE'RE DOING TO ADAPT

Sights and Sounds: Snow Goose Festival

Video courtesy Scott Wild, Northwest Videographer

Sights and sounds of Port Susan Snow Goose & Birding Fest at our Port Susan Bay Preserve!

Learn more about our work in Puget Sound

Timelapse: Port Susan Bay Shorebirds

Video by Joelene Boyd, Puget Sound Stewardship Coordinator /Interim Stewardship Director

A timelapse camera was set up at our Port Susan Bay Preserve in an attempt to capture the King Tides. We ended up getting so much more, see what our cameras captured in the video above!

Learn more about our work at Port Susan Bay

Out in the Field at Port Susan Bay: Edmonds Community College

A Q & A Interview with Restoration Ecology Student Zacharay Bigelow

Written & Photographed by Marlo Mytty, Conservation Coordinator Puget Sound Programs

What is your major?

I’m planning to major in Environmental Sciences and hopefully attend Huxley College of the Environment at Western Washington University.

What type of restoration projects are you most interested in?

Restoration projects that involve the community, like the Port Susan Bay project. I have travelled quite a bit and observed and been involved in restoration projects that the community doesn’t see or know about, which is one of the major problems in restoration. If the community doesn’t see the work going on, they aren’t going to care about it. Outreach and getting people out there, like volunteer groups, is important.

What do you hope to do after graduation?

Two things – to travel more and see what projects are going on; and to be skilled at what it takes to start a non-profit. I want to have the skills to be able to set one up in a part of the world where there is less funding available and more need. Also to start one that is a leader in worldwide conservation efforts.

What interested you most about today’s tour/what will you take away?

The process of the recovery of the habitat. What really struck me is how much of this habitat there must have used to have been. This project supports hundreds of thousands of birds and it’s cool to see a piece of history/what the area historically must have been like.

What would you tell someone who thinks that the current environmental challenges we are facing are too big to overcome?

I read a quote once on a wall in a big CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) cabin that is a testament to how much work one person can do. The quote was something like “The biggest mistake a person could ever make is deciding to do nothing because it was not enough.”

That fits with this and the scope of problems we are trying to fix. It’s not just what’s going on now, but what’s been done historically; and it’s just now that we are really trying to change a lot of these things.

What do you think is the most important thing for The Nature Conservancy to be working on?

To continue engaging the public in environmental issues. Education has the capacity to spread much further through society than just work does. If you inspire a single person, they can keep reaching out to others.

That’s what I’m hoping to do.

Sharing the Beauty of Port Susan Bay

A tour of the preserve with the American Planning Association

Written & Photographed by Marlo Mytty, Conservation Coordinator Puget Sound Programs

It was great to get outside last weekend and lead a tour of The Nature Conservancy’s Port Susan Bay preserve for nine people, mostly planners, who were in Seattle for the American Planning Association’s National Conference. Getting out of the office to see and share the story of the restoration at the Preserve with others not familiar with the project is what helps make our work on the ground more real and meaningful for me.

The folks who attended brought diverse backgrounds and perspectives and came from afar - from Nebraska, Georgia, Virginia, Louisiana, Montana and British Columbia! It even included a student from Iowa and a former TNC staffer who helped develop the Natural Heritage program in the 1980s. The weather cooperated and the visitors were treated to views of the Cascades and Olympics and fertile farmland on the drive up. The birders in the group donned their binoculars upon arrival to watch birds at the site.

There was a lot of interest from the group around what nearby farmers, landowners, and the local community thought about the project and how they were impacted by it. It highlights the importance of working with neighboring landowners and the community for folks working on these types of projects in all geographies.

In the case of Port Susan Bay, all stakeholders were included in the process early on. The project provided not only ecological benefits, including new habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon, but also met the co-equal goal of enhanced flood protection for nearby farms and homes. There was significant support from the locals. This model of designing projects to meet both ecological and community goals is something we are replicating across Puget Sound through our Floodplains by Design initiative.

At the end of the tour, participants were reluctant to get back on the road. Yet, it made for a perfect ending, when upon exit, a Northern Harrier flew by the bus and flashed its white rump patch!

Meet Joelene Boyd

Meet Joelene Boyd

Joelene is our Stewardship Coordinator for the Puget Sound Program. If you have been to our many preserves and restoration projects in the Sound, you might recognize her!

Get to know her a little better!

Where are you originally from?

That questions a little difficult to answer. I’m an Army brat born near Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

If you could live anywhere, where would it be?

I live in a pretty special place already, between Cascade Mountain Range and the shores of Puget Sound. However, I love sagebrush country; the open skies, the unexpected beauty of wild flowers, and oh yeah, the sun.

What is your favorite part of nature?

The vastness and unexpectedness of it.

Favorite hobby?

Reading, hiking, jogging, road biking. But most of all I just really enjoy spending time with my family and seeing things through the eyes of my toddler son.

Favorite food?

Wild mushrooms! I’ve foraged quite a few; morels, chanterelles, king boletes…

Port Susan Bay Day

We had a fantastic time learning and witnessing how successful restoration can be for our waters around Puget Sound. Everyone had such a great time learning, going birding and enjoying the massive ice cream sandwiches to top off our day with nature at Port Susan Bay!

We loved having everyone come out and visit! Did you get your photo taken? Check out our photo gallery on Facebook, and let us know if you’d like a copy!

Port Susan Bay is one of The Nature Conservancy’s beautiful nature preserves in Washington, highlighting collaborative efforts to restore our floodplains and keep Washington beautiful.

BIG: Topic of the day at Puget Sound floodplains conference

By: Julie Morse, Project Ecologist

That’s a first. Trust me, I’ve attended a lot of conferences with Floodplain Managers, Biologists, Engineers, City Planners, etc… And I have NEVER seen this kind of inspirational language show up in the middle of a PowerPoint presentation. Presentations at these kinds of workshops are generally pretty dry - lots of numbers, graphs and figures. Sometimes the creative speakers will throw in a video or pretty pictures to keep people awake. But let’s be honest, these workshops are generally pretty dry with lots of “Blah, Blah, Blah…”

Yesterday was different.

Yesterday, The Nature Conservancy in Washington convened a workshop for people working in Puget Sound as part of our Floodplains by Design Partnership. Despite the fact that it was a beautiful June day and plenty of people were off of vacation, despite the fact that Seattle was experiencing one of its epic traffic days, despite the fact that there were other big meetings happening in the area, despite all that, more than 150 people showed up to hear what’s happening with Floodplains by Design.

Representatives from five Congressional offices and one U.S. Senator’s office. Staff from seven counties were there along with representatives from four of Puget Sound’s tribes. Farmers, businesses that work in flood plains and agencies came. What’s more - people even came from across the state (Yakima) and even out of state (Oregon) to hear what was happening in Puget Sound.

There was a buzz in the room, and with good reason. Among the successes we celebrated:

- In 2013, over $44 million in state legislative were appropriated for integrated floodplain projects

- This funding has helped catalyze 15 big projects – providing multiple benefits to a number of communities including reduced flood risks, restored salmon habitat, improved water quality, agricultural infrastructure upgrades and enhanced public access and recreational opportunities.

Colonel Estok, outgoing Seattle District Commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers thanked everyone in the room for their efforts working collaboratively, and The Nature Conservancy for being the glue that pulls these different groups together. He reflected on three years of incredible progress.

But it was also time to look forward. Here are some huge opportunities for collaboration and getting Big Things Done in the coming year:

- A new capital budget request highlighting at least $50 million in compelling, ambitious, needed projects

- Potential ballot initiative to create an even larger, dedicated revenue source for multiple benefit floodplain projects

- Colonel John Buck was introduced as the new Seattle District Commander for the Army Corps of Engineers, an important partner in the FbD Partnership

The best presentation of the day was the last, given by our government relations director Mo McBroom. Through Mo’s talk I could see her spunky enthusiasm was going to battle with her more subdued professional side. Mo was clearly trying to contain her excitement about the potential for the legislature to help support, and be a leader nationally, in addressing water issues - whether it’s too much water (flooding), too little water (irrigation needs), or nowhere for the water to go (stormwater). I’m not sure trying to contain her enthusiasm was really working for her, in fact quite the opposite; I thought her enthusiasm was contagious.

Mo ended her presentation with reiterating the phrase of the day - Think BIG. Believe BIG. Act BIG. And the results will be BIG. There are BIG things happening in Puget Sound. Yesterday I felt incredibly proud to be part of it.

To hear more of what people are saying about Floodplains by Design, please visit our website – http://www.floodplainsbydesign.org/perspectives/