As 2023 draws to a close, Jamie Stroble, Director of Climate Action and Resilience reflects on the link between healthy community relationships and a healthy climate. She lists several ways every person can contribute to a thriving planet.

Jamie Stroble, TNC Director of Climate Action and Resilience

My experiences in the environmental sector are wide and varied—spanning a background in forestry and field work, community organizing, youth leadership development, urban planning, government and policy work. Throughout the years, I have attended many convenings with climate change as a centerpiece topic, often organized by larger environmental non-profits and organizations with abundant and well-established resources. Many of these organizations, such as The Nature Conservancy, benefit from a long legacy of major donors and have cultivated significant influence over time. These conferences and events often struggle to draw diverse representation, both among speakers and audience members alike.

My position at The Nature Conservancy affords me access to these spaces where the world’s prominent leaders and voices network and strategize. But, this wasn’t always the case early in my career. When I worked primarily within grassroots organizations, we found it difficult to afford these opportunities, as time, money, capacity and access were limited. Grassroots organizations operate in survival mode, so it’s no wonder these convenings are largely attended by predominantly white-led institutions (PWI) with large budgets.

When I started as the Director of Climate Action and Resilience at The Nature Conservancy in Washington (WAFO), I saw an organization with much potential for systemic level impact on climate change, for the benefit of people and critical ecosystems across our state. I knew that in order to achieve that impact, WAFO would need to acknowledge its position of power and privilege, how it was established, and how that power is being used. I am grateful there are many colleagues at WAFO who agree that how well we tend to each other impacts how well we tend to our Earth. Historically, many PWIs have not reflected on how they can best support frontline community partners, or how their access to resource is rooted in a long history of erasure of Indigenous peoples from the landscape in the name of “preservation of wilderness” and traditional conservation.

Near Pilchuck Creek on the Stillaguamish Reservation. Photo by Hannah Letinich.

In fact, according to Dorceta Taylor’s book The Rise of the American Conservation Movement (2016), the history of environmentalism in the United States “reflected elements of settler colonialism, cultural nationalism, and frontierism as well as Transcendental and romantic thought.” Wealthy business elites of the nineteenth century built an exclusive system by which only those who can afford to escape over-industrialized and deteriorating cities were able to enjoy nature’s beauty. By sequestering people of color to reservations and zoned districts of cities, early conservationism promoted the illusion of “untouched,” “uninhabited” and “pristine” landscapes, which were available for recreation and exploitation without input from the original keepers of the land.

In order for contemporary conservationists to have real impact on our climate at this critical time, we must acknowledge a legacy that Dr. Jessica Hernandez describes as being, “whitewashed, meaning that Indigenous contributions to science are ignored, suppressed and not acknowledged”(Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science, 2022). She says, “We cannot just solely identify Indigenous teachings and remove Indigenous people out of this narrative, as co-option of Indigenous knowledge contributes to the oppressive narrative we currently have in the environmental discourse. These teachings do not and cannot be applied in the Western scientific paradigms or frameworks without incorporating Indigenous peoples as well.”

The momentum and severity of climate change requires all of us work together. To do this equitably, we must confront common methods of work that are rooted in Western culture, such as exceptionalism, quantity over quality, and productivity over integrity. These Western paradigms have manifested in over-extraction of natural resources, excess carbon (CO2) emissions, water and air pollution, and increasing wealth inequality that leaves many people less resourced to withstand the impacts of climate change.

Here at WAFO, our staff have been working on a new strategic framework over the last year, that re-examines our positionality with the environmental movement, and pivots us toward work where we can have the most meaningful impact with the extraordinary access to resources and decisionmakers that we have. I am so proud of the hard work of our staff over the last year to dive deep into the questions: Why us? Why now? And what impact can we have within the broader movement to address climate change? This framework aims to foster right relations with Tribal and First Nations, center racial equity and environmental justice, and leverage learning and innovation. These three focuses are intended to become deeply integrated in all of our work, while orienting all projects around opportunities for climate mitigation and adaptation impact. My hope is that this sets us up for meaningful and impactful work, in partnership with other environmental organizations, Tribes, and community partners, that decenters us and focuses on our collective impact on climate change.

The mainstream environmental movement is at a critical turning point, one where we could collectively have more impact by centering and resourcing the leadership of Indigenous and frontline community leaders in the climate sector. We have the opportunity to change the historic narrative of hoarded power and competitive resourcing to one that is far more mutually beneficial to both the empowered and the disempowered. This is an opportunity for The Nature Conservancy and other mainstream PWI environmental organization to center climate equity in how we approach our work.

As I look back over 2023, we have made brave and crucial steps forward at The Nature Conservancy in Washington towards climate & equity. In an organization with such a storied legacy and history, I know this progress is but one step forward, but it is a turn in a new direction that opens so many more possibilities. I am committed to pushing my friends and colleagues (both in and out of my organization) to center care and relationships, to reach into where we have opportunities to be more generous, and be committed to continual growth and learning.

Here are suggestions for meaningful relationship-building & further learning:

Listen Indigenous and frontline community leaders often feel they are screaming into a void. Actively seek ways to create space for these voices to lead and be heard.

Embrace We are at the beginning of a necessary acknowledgement of the harmful history of conservation rooted in colonization. We must be willing to discuss this in order to make an impact on our climate crisis.

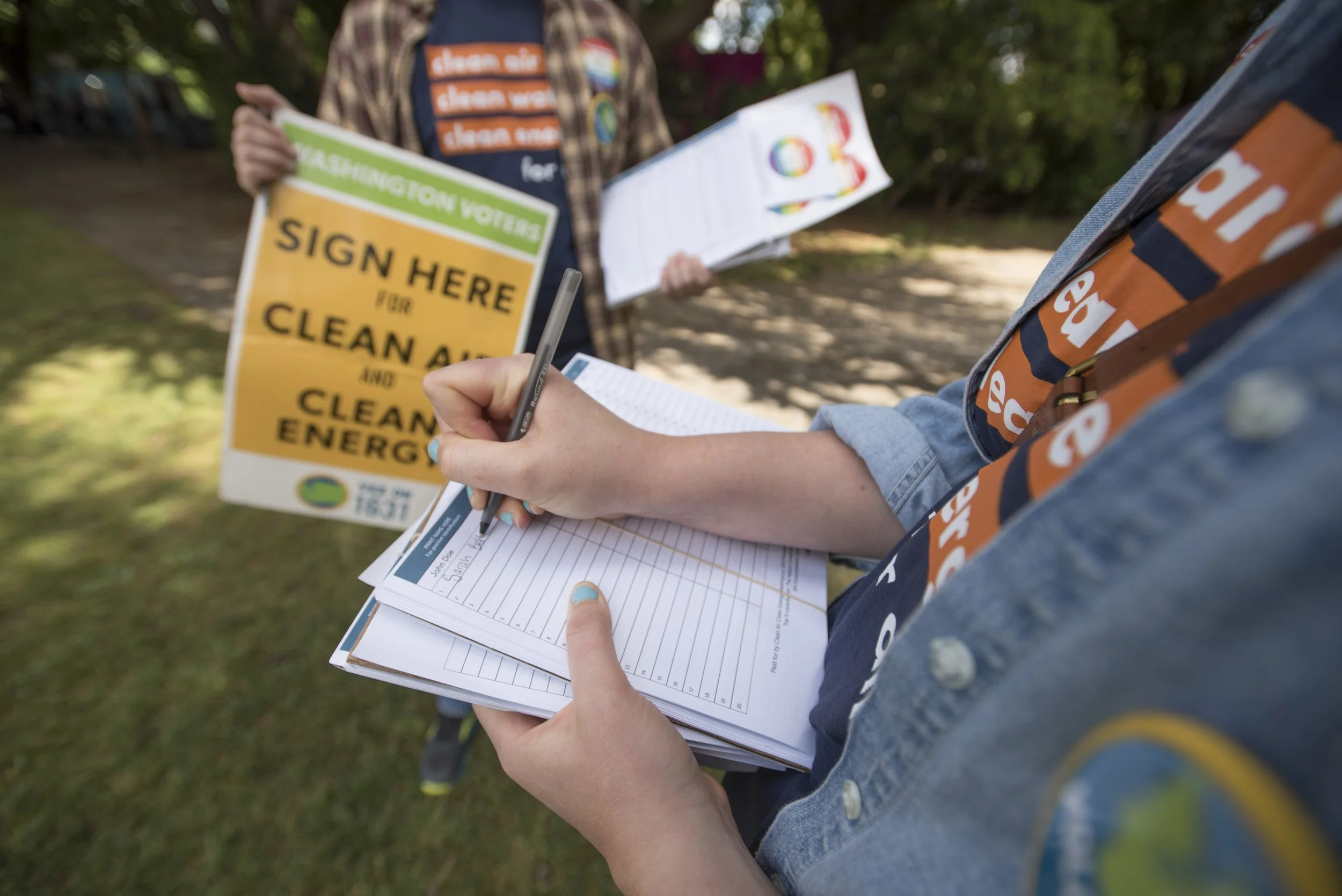

Extend If you find yourself in close proximity or with access to power and resources, look for ways to extend this and share with others.

Engage Show the leaders in your community that you care about centering Indigenous and frontline community leader’s voices when discussing the state of our climate.

Learn As 2023 comes to a close, I encourage you to commit to learning more about the climate.

Brush up on your climate vocabulary and explore more from 2023’s Climate Chronicles.

Read As 2023 comes to a close, I encourage you to commit to reading more about the climate.

The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection by Dorceta E. Taylor

As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock by Dina Gilio Whitaker

Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science by Jessica Hernandez

All We Can Save: Truth Courage and Solutions for the Climate Crisis edited by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine K. Wilkinson

Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance by Edgar Villanueva

United We are Unstoppable: 60 Inspiring Young People Saving our World by Akshat Rathi