By Stephanie Burgart, Contracts and Conservation Program Coordinator

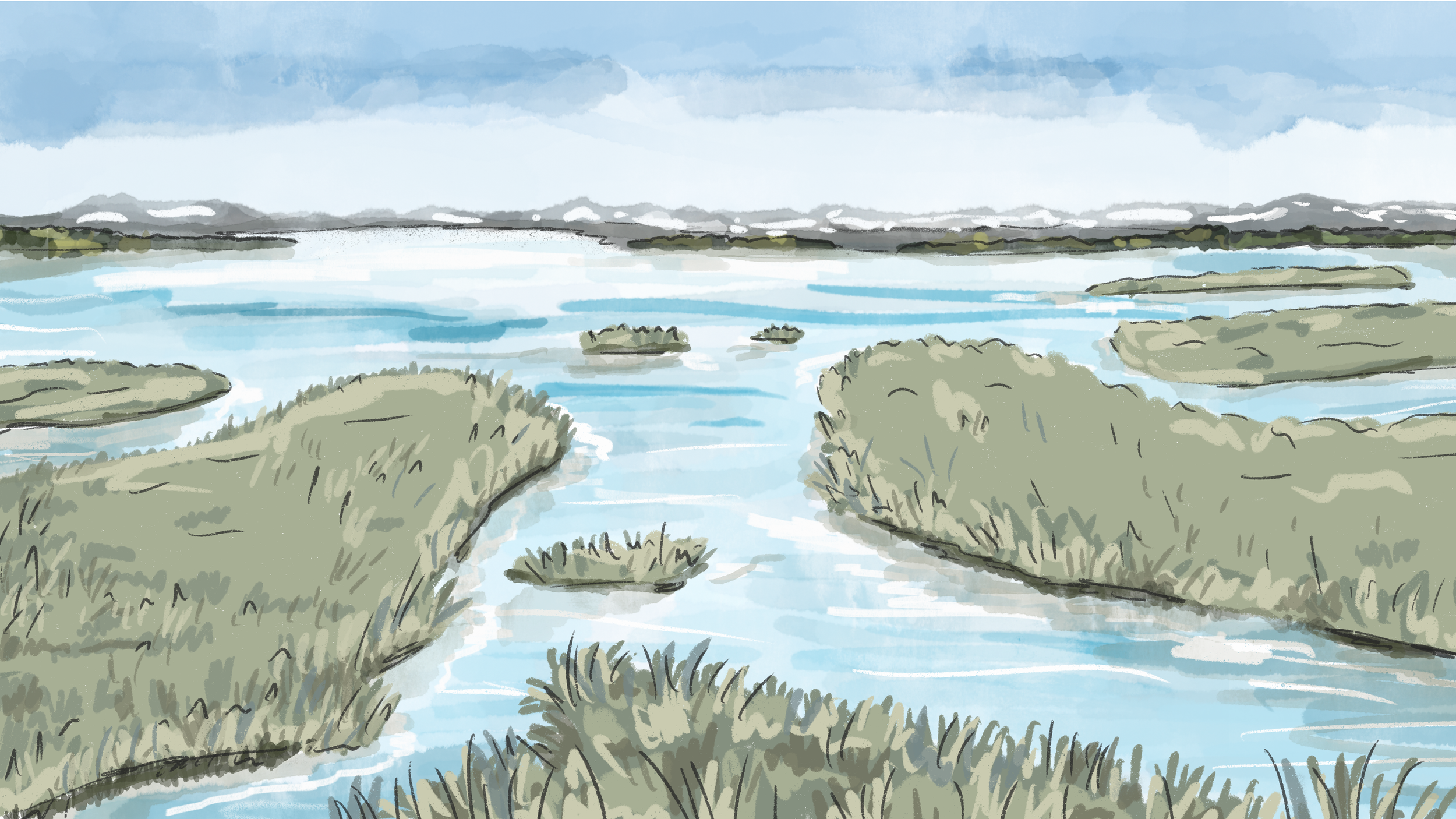

To many, the wide expanses of marsh mud looks desolate. The tide rolls in, soaks the muck and then rolls back out leaving slick spots. However, to scientists, naturalists and lovers of soils, it looks far from bleak. Marsh soils are teeming with life!

Roger Fuller, ecosystems ecologist at Western Washington University, has studied the Port Susan Bay estuary and marshes for more than 15 years and presented his work to our staff last month. One of the largest restoration projects The Nature Conservancy in Washington has ever completed is the Port Susan Bay tidal marsh restoration project.

The Stillaguamish estuary is a major feeding ground for salmon and sturgeon, and the estuary is second only to the Skagit River delta in numbers of shorebirds, waterfowl and raptors supported. But the tidal marsh here has been disappearing over recent decades, and with it go the diatoms.

What Are Diatoms?

Diatoms are a type of algae and the second most common form of life on Earth after bacteria. They may not be as charismatic as salmon or great blue herons, but they surpass them in abundance. Have you ever seen a slick greenish spot while stomping out in a marsh? Diatoms! Have you seen lines and trails through the green? Those are worms eating the diatoms! Do you notice little bird prints following the trails? Shorebirds! The food web multiplies in many ways, and it all goes back down to the diatom.

These single cells came to be at some point during the Jurassic period. They are producers, and they need water — thus they are found in oceans, lakes, rivers, bogs and even damp moss. Their unique feature is a cell wall made of silicon dioxide, which is the main component of glass. These little glass-housed cells form part of the basis of all marine food chains, and they produce approximately 20 to 40 percent of the oxygen on Earth.

Dike and channels on the rivers create high flow rates, so the water doesn’t have enough time to let sediments settle out in the marsh. Low winter snow fall creates low summer flow rates, which increases the salinity of the estuary — due to less fresh water coming in. These, and many other factors, are affecting the estuary’s ability to sustain and harbor life, like the diatoms. Without the diatoms, the larger creatures begin to decline.

So next time you talk a walk near the marsh, inhale that deep soil smell tinged with salt and know there are millions of little diatoms working hard to sustain a food web, and people working hard to sustain the environment for the diatoms.