From thousands to millions to hundreds of millions of gallons, the Aurora Bridge Bioswale Project paints the story of scaling green infrastructure projects to help our salmon and orca.

Digging in the Dirt Creates Budding Interest for Schoolchildren

Room for Nature in Our Cities

Protecting clean water takes a village

Written by Tammy Kennon

The Puget Sound region is a sprawling, productive ecosystem with a burgeoning population. Protecting this wonderland means bringing together an equally sprawling number of interests: counties, cities, engineers, scientists, non-profits, large corporations and the public. Is that even possible?

A pilot project in the Perrinville Creek basin says yes.

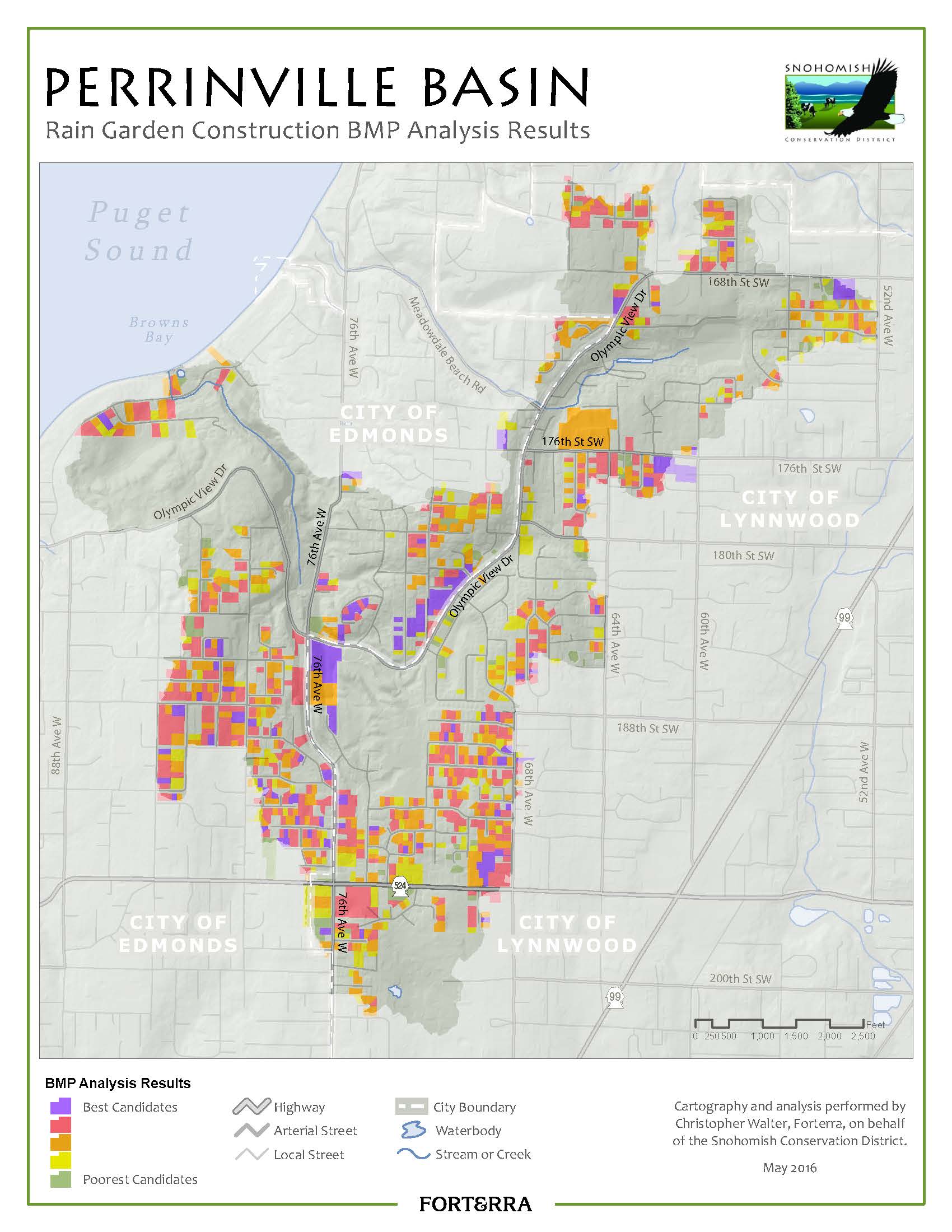

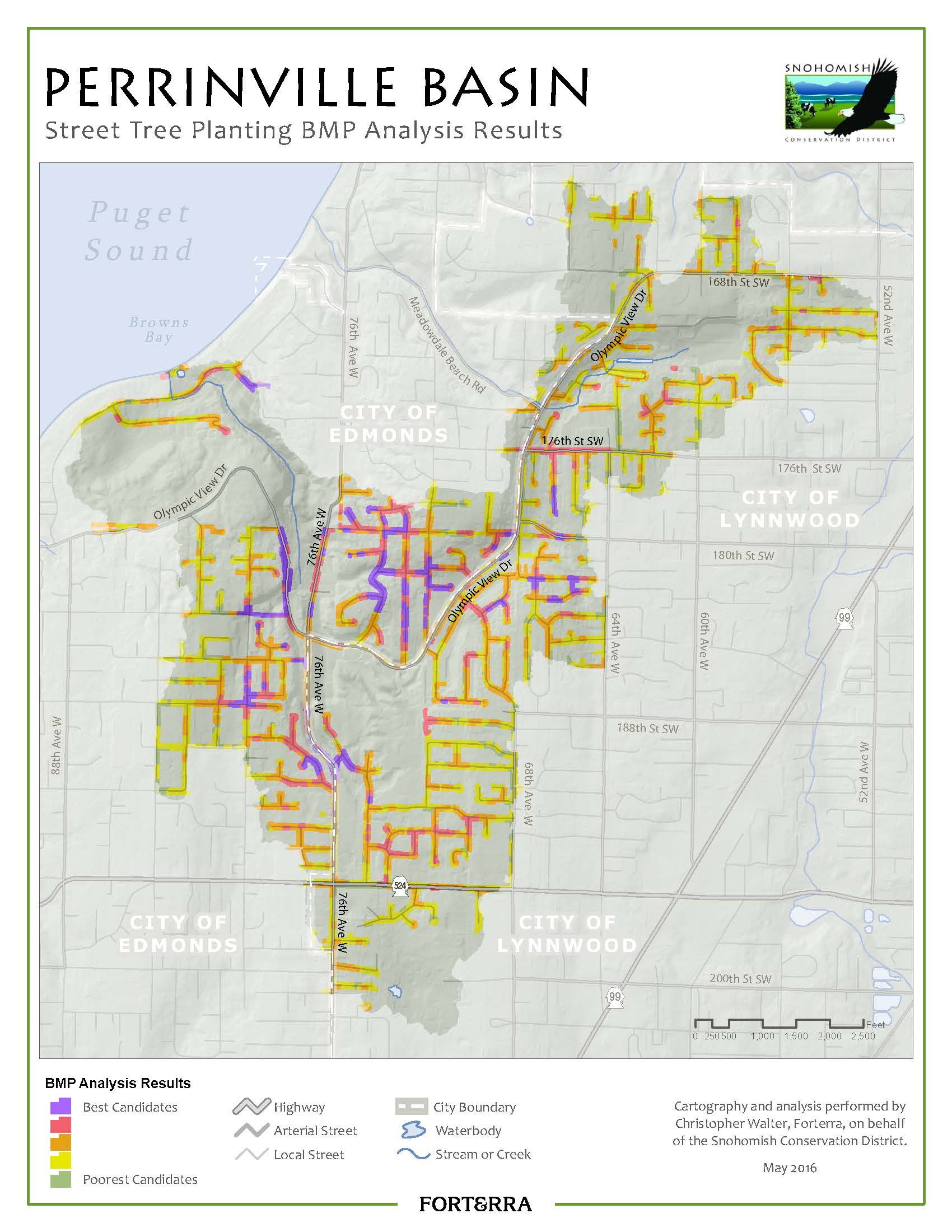

The Perrinville Creek basin, located in Snohomish County, is a small watershed that packs a punch. As rainfall runs over the paved surfaces and roof tops its 1200 acres of uplands drain polluted stormwater into the creek and eventually into Puget Sound. The basin, which includes the cities of Edmonds and Lynnwood, is part of the Snohomish Conservation District, which offers free help to residents to conserve natural resources.

Bringing together all concerned parties to address polluted runoff in the basin posed a daunting hurdle, but with grant money from Boeing and The Nature Conservancy, the Snohomish Conservation District met the challenge. Working with the city of Edmonds, Edmonds Community College and a nonprofit sustainability organization, they identified, evaluated and prioritized stormwater reduction opportunities in the creek basin.

Their first step was to gauge the interest of the local community, so they sought help from Dr. Thomas Murphy, Chair of the Anthropology Department at Edmonds Community College. Dr. Murphy and his students canvassed homeowners in the basin to measure their interest in natural solutions.

“We let the results speak for themselves,” said Riley. “It was overwhelming.”

Nine out of ten homeowners expressed willingness to install a rain garden in their neighborhood right-of-ways -- and even on their own property. And the majority of community members were willing to help maintain green infrastructure in public spaces.

To identify optimal locations for green infrastructure, Snohomish Conservation District also enlisted the help of the nonprofit Forterra, a regional sustainability organization, to analyze the basin.

For more information please visit the Community-Based Stormwater Solutions for the Perrinville Basin Report

Learn more about our work in cities

Bellingham Joins the Depave Revolution

Written By Tammy Kennon

Photographed by Puget Sound Conservation Districts

Squalicum Creek just got a little cleaner. A new rain garden carved out of two parking spots at Yeager’s Sporting Goods in Bellingham will filter pollutants out of more than 70,000 gallons of stormwater annually, sending clean, naturally filtered water into the creek.

Squalicum Creek flows into Bellingham Bay, part of the complex system of water bodies known collectively as Puget Sound, home to orcas, salmon and the giant Pacific octopus – and, unfortunately, the destination of the region’s polluted runoff.

Stormwater, the rain and snow that runs off of roads, roofs and parking lots, represents the single biggest source of pollution in Puget Sound. While a good rainstorm might cleanse our buildings and streets, the runoff sends toxins, sediment, nutrients and bacteria into our waterways. And there’s a lot of it. An estimated 14 million pounds of chemical pollutants run into Puget Sound annually, threatening wildlife, fish and people. Research has shown that this toxic runoff can kill adult salmon in less than three hours.

Bringing nature back into our cities helps purify otherwise polluted runoff using nature’s own filtering system. An acre of green space serves a dual purpose, sending only 208,000 gallons of clean runoff into waterways and at the same time replenishing vital groundwater with 311,000 gallons annually. By contrast, a single acre of paved surface, the size of a 150-car parking lot, sends a million gallons of polluted runoff into Puget Sound every year.

The good news is that even small green spaces, such as the two parking spots at Yeager’s, have an impact.

With funding from Boeing and The Nature Conservancy, the Puget Sound Conservation Districts (PSCD) created a Stormwater Action team to leverage the skills and resources of the region for districts that don’t have the capacity or experience to implement stormwater projects on their own.

“Through this team, which is made up of local leaders partnering across Puget Sound, we suddenly have a very big reach and can replicate top programs in the region,” said Kate Riley, a Community Engagement Program Manager in the Snohomish Conservation District. “The city of Bellingham wanted to try a pilot depave case.”

Yeager’s was identified as a high-impact site for depaving, because of the size of the parking lot and its proximity to the creek. And, it also helped that the owner grew up fishing Squalicum Creek.

“The area here has a special place in my heart,” Yeager’s owner John “Westy” Westerfield told the Bellingham Herald. “When we had this opportunity, we couldn’t pass it up.”

Volunteers from Yeager’s staff broke up and removed the asphalt in June, and the rain garden was planted this month with plants that are easy to maintain and tolerant of wet soil.

The Nature Conservancy, working with partners such as Boeing and the Puget Sound Conservation District, continues to mitigate polluted stormwater with projects like the new rain gardens in Bellingham and Tacoma. These successful depave ventures encourage communities to think about where unused pavement can be replaced with nature to energize our waterways and our neighborhoods.

You can learn more about installing a beautiful rain garden in your own yard or neighborhood at City Habitats.

Making a Difference One Rain Garden at a Time

October 22nd was a successful (and sunny) day for communities and Puget Sound! Make a Difference Day (MDDAY) is a one of the largest annual single-days of volunteer service nationwide. With the help of hundreds of volunteers and dedicated partners, we truly witnessed the difference happen right before our eyes. Check out the amazing outcomes from a few of the MDDAY projects and see the photos from each event.

MDDAY Project Outcomes

8 Rain gardens

1 Green Wall (Seattle’s longest at 136 feet in length!).

4,000 sq. ft + of depaved space planted with native plants.

150 Rain Barrels

Around 3000 plants planted

Around 300 volunteers

A rough estimation of the combine impacts of these MDDAY projects will be able to reduce about 473,000 gallons of polluted runoff that enters Puget Sound each year. That’s a half a million gallons of harmful pollution being redirected to attractive, healthy garden spaces that was made possible by hard working volunteers and dedicated staff from many organizations!

Read more about the success of a few these projects below

Tacoma

After removing 4,000 square feet of unsightly pavement from two asphalt islands in Tacoma, staff from Pierce Conservation District and City of Tacoma led a group of 90 volunteers, including staff from Lowes and KING5, who planted hundreds of trees and shrubs to beautify this space. By removing this impervious pavement the site will allow 86,400 gallons of rainwater to naturally infiltrate into the ground, water the plants, and reduce the amount of pollution each year.

Photos by Christin Hilton, Conservancy Urban Partnership Director

Poulsbo

Around 40 volunteers helped Kitsap Conservation District and the Conservancy to plant 6 residential rain gardens complete with native and edible plants! These rain gardens will help clean Liberty Bay by reducing the amount of polluted run off that flows into this body of water.

Photos by Emily Howe, Conservancy Aquatics Ecologist

Mill Creek

Volunteers from Lowes Heroes, KING5 News, and Phillips Law Firm participated in some friendly competition while building rain barrels for MDDAY. The barrels used were re-purposed from containers for fruit juice concentrate, complete with a fruit punch aroma. After a demonstration from Snohomish Conservation District staff, these fast working volunteers built 150 rain barrels in less than 2 hours! Rain barrels help the environment by capturing rain water that flows off of rooftops before it runoffs onto roads and driveways, where it picks up pollutants and eventually flows into Puget Sound.

Photos by Kat Mogan, Puget Sound Communication Partnership Manager

Learn More about our work in Cities

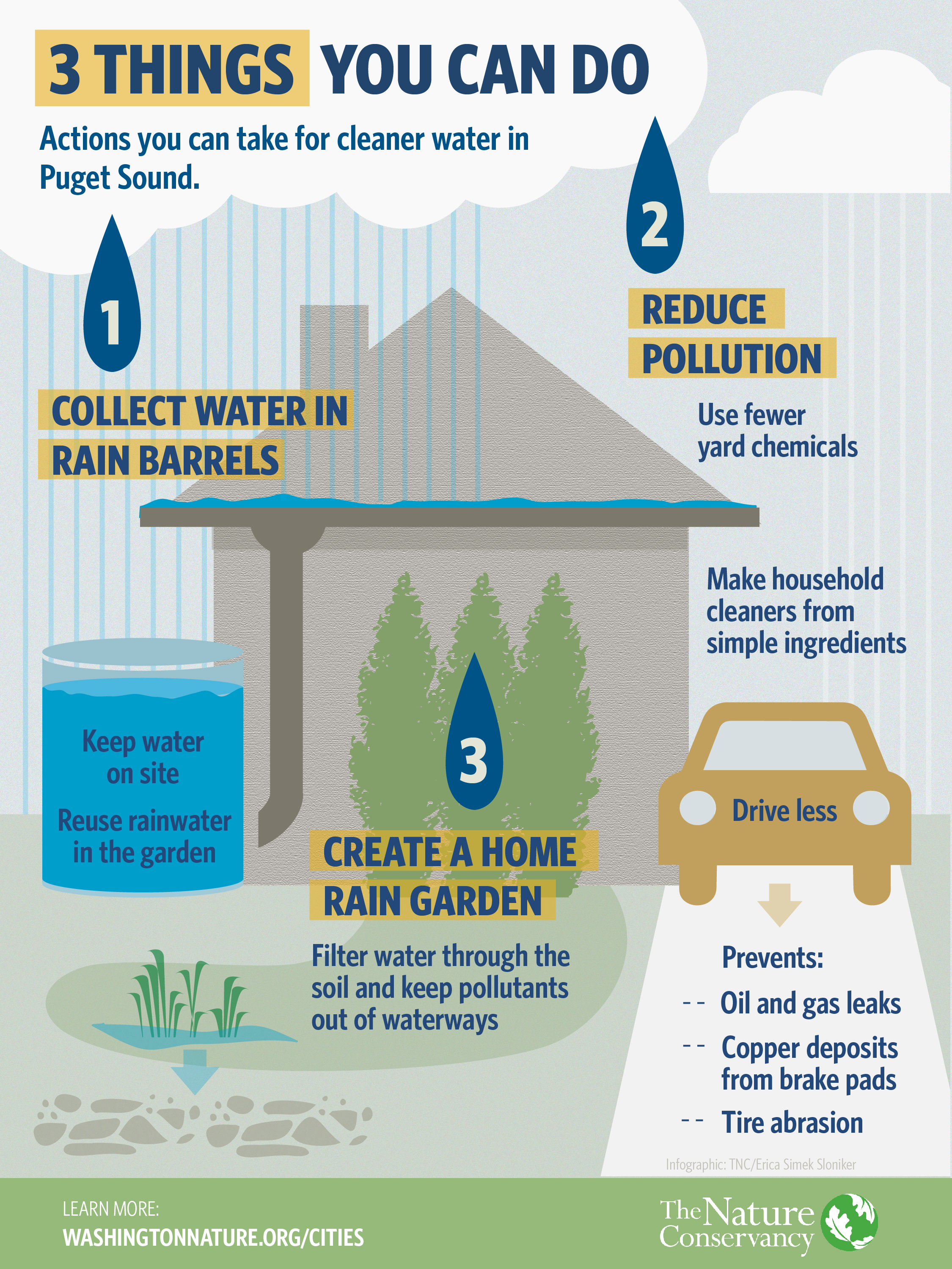

Take Action for a Cleaner Puget Sound

With all this talk about the negative affects polluted run off has on Puget Sound, here are a few things you can do to make a positive difference. Actions like capturing rain, building rain gardens and driving less can all help reduce the impacts of polluted run off and move towards creating a cleaner and healthier Puget Sound. Explore the infographic below to learn more about what you can do.

Infographic Created by Erica Simek Sloniker

The Truth About Puget Sound

Written by Stephanie Williams, Program Coordinator

The Pacific Northwest is known for its good looking bodies… of water, that is.

If people don’t know much about Puget Sound, they tend to at least know that this region has a wealth of gorgeous views of blue lakes, tree-lined rivers, waterfalls, and meandering creeks, not to mention the Sound itself. While this is something to boast about, it is also quite deceptive. These breath-taking views are hiding a serious problem that can only be seen with an up-close look. The water in Puget Sound looks healthy and is often described as pristine, but the truth is that it is in very bad shape.

What isn’t easily visible in the picturesque Elliot Bay, Skagit River, or Lake Washington is polluted run-off from our urban and suburban areas. While it may not be a floating plastic bag or a six-pack ring, the poster children of aquatic litter, polluted run-off is having a severe impact on salmon, marine mammals, and the entire ecosystem (humans included). It is the number one threat to water quality in Puget Sound.

But what is polluted run-off? What is this ghostly and invisible thing?

Polluted run-off, which is also referred to as “stormwater,” is rain water that rushes over pervious surfaces, such as buildings, roads, and sidewalks collecting dangerous oil, bacteria, chemicals and other pollutants along the way. Unlike sewage, which passes through treatment facilities, polluted run-off ends up in the nearest body of water dirty and untreated.

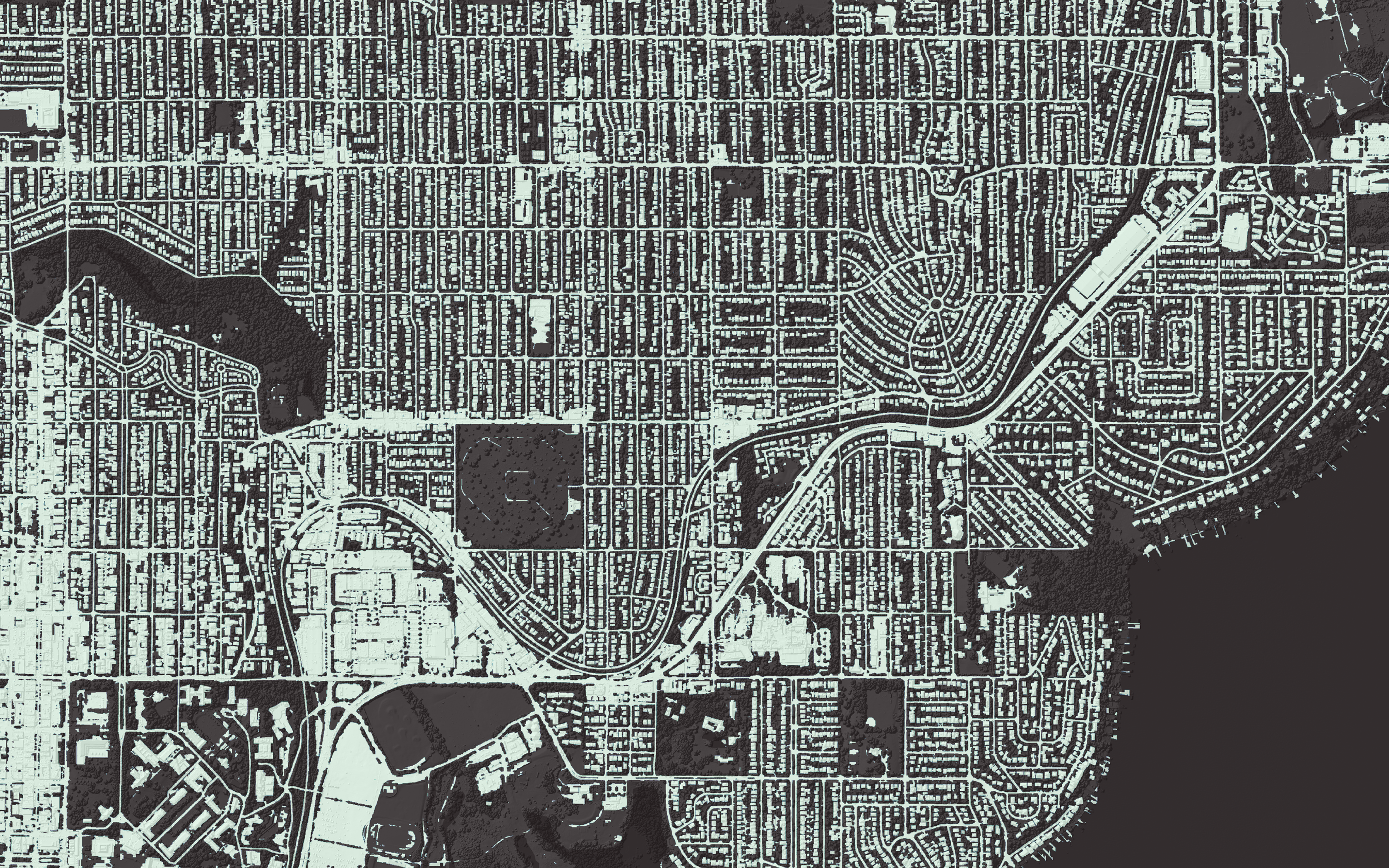

Imagine what your city or town looked like before humans built there. It was most likely a rich forest, lush with vegetation and healthy soils. Back then, the rain would catch on trees and be absorbed into the forest soils, which both slowed and cleaned the water as it made its way toward Puget Sound. Over time people greatly changed the landscape by erecting tall buildings, houses, and roads, all with hard surfaces that left nowhere for the rain water to go. To avoid flooding, storm drains were built to pipe the rain water away from the city to streams, lakes and the Sound. Water that used to soak into soils and groundwater, supporting a healthy ecosystem, now runs off and causes more frequent erosion and flooding in addition to its devastating impact on salmon and other species.

The problem of polluted run-off is not as simple as sea turtle caught in a six-pack ring. It is very complex and its inconspicuous nature only makes it more difficult to bring to people’s attention. Check out cityhabitats.org and washingtonnature.org/cities to see what The Nature Conservancy and its partners are doing to raise awareness of polluted run-off and affect change for salmon and for ourselves.

How Can I Make My Home More Green

Interested in building a rain garden but don't know how? Follow these guidelines and help us create a clean and healthy Puget Sound!

Creating, Connecting & Learning with Habitat Network

Did you know that the plants and natural features along your street, in your yard, and at your favorite playground or park improve your quality of life AND provide habitat for dozens of plants and animals?

The Nature Conservancy and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology have launched Habitat Network, a free online citizen science tool that invites people to map their outdoor space, share it with others, and learn more about supporting wildlife habitat and other natural functions in cities and town.

In Puget Sound, 75% of cities and towns are covered in impervious surfaces. These hard surfaces, like driveways, roads, and roofs, prevent rainwater from soaking into the ground. When it rains, water running off impervious surfaces picks up pollutants and debris. The polluted runoff can then end up in our nearest water body.

Habitat Network offers alternate solutions for yards, parks and other urban green spaces to reduce polluted runoff while supporting birds, pollinators, and other wildlife. Habitat Network can be used on properties of all sizes and types – from a shared urban garden in a city park to a large suburban backyard or a school yard.

What can a Habitat Network help you do?

- Manage rainwater

Attract a variety of birds to your home, school, or business

Help protect bees and other pollinators

Compare your map to other network members and get inspired!

“Science shows us that small changes in the way properties are managed can make a huge impact towards improving our environment,” said Megan Whatton, project manager for Habitat Network at The Nature Conservancy. “Creating and conserving nature within cities, towns and neighborhoods are key to global conservation.”

The mapping tool is also a social network, inviting participants to share information and learn from their neighbors. And over time, the self-reported information from citizen scientists using the Habitat Network will provide data the Conservancy can use to understand how much habitat exists in our cities and towns and what role that habitat can play in benefiting wildlife and humans.

In Washington, we’ll be using it to track progress on our City Habitats’ goal of building 20,000 rain gardens in the Puget Sound region.

Help us learn more about habitat in our cities and towns by making map on Habitat Network! Go to www.habitat.network to sign up for an account and get started mapping, sharing, and learning about sustainable practices you can implement in backyards, schoolyards, parks, and corporate campuses.

Visit habitat.network to join!

Rain Gardens: Below the Surface

Rain gardens are a great way to make any neighborhood shine. But there is more to a rain garden then the colorful flowers, trees, and grasses you see at the surface. See the image below to learn more about what is happening underneath a rain garden.

Infographic created by Erica Simek Sloniker

Learn more about rain gardens here

Sign up for Make a Difference Day

Bringing Nature into our Cities

We're looking to nature to solve our stormwater problems! By bringing nature into our cities, we can reduce the amount of polluted run off that travels into Puget Sound and protect our iconic marine life. See the infographic below to learn more.

Rain Gardens: A Beautiful & Simple Solution

Written by Stephanie Williams, Program Coordinator

Photo Cred: Zoe van Duivenbode & 12,000 Rain Gardens

What exactly is a "rain garden"?

A rain garden is a bowl-shaped garden specially designed to catch rain water from roofs and pavement. It helps to slow down the water and clean it naturally before it runs off into our streams, lakes, rivers, and ultimately Puget Sound. Without simple, natural solutions like rain gardens, rain water picks up nasty chemicals and bacteria from our pavement and built environment. This contaminated water then rushes too quickly into larger bodies of water, where it has very harmful impacts. Untreated polluted runoff can kill an adult salmon in as little as three hours!

Although a rain garden’s main purpose is to prevent the number one polluter of Puget Sound, these natural beauties have other benefits as well. Here are just a few to get you started:

1) Installing a rain garden can be a simple step to beautifying a community space or adding curb appeal to your home. The different colors and textures from stones, grasses, flowers, and plants in your rain garden will break up a boring landscape. Some communities in Puget Sound have already decided to take out unsightly and unnecessary pavement in order to add rain gardens. What a great way to instill pride and a sense of community in a local public space!

2) By using native plants, rain gardens can also promote biodiversity and attract wildlife such as birds, butterflies, and bees. Of course these creatures are fun to look at, but they are also important pollinators for growing many of our favorite local foods.

3) Since rain gardens slow the flow of water, they also prevent flooding. As climate change gives our region more intense rain events, rain gardens are a plan for resiliency.

4) Rain gardens are a great way to give your neighbors yard envy! Check out this video about the unquestionable community support for installing rain gardens in Snohomish County!

Polluted run-off is a very serious threat to Puget Sound waters. Rain gardens are such an easy solution for tackling this issue and reaping additional benefits along the way. If you’re still curious, one way to understand a rain garden is to see one first hand. Click here to see where there might be a rain garden in your area.

Learn more about our work in Cities

Find out how you can win a rain garden makeover

Puget Sound – It’s Time to Tackle Stormwater

Green Infrastructure Summit Brings Leaders together for Innovative Natural Solution

Written by Jeanine Stewart, Volunteer

Photographed by Paul Brown, Northwest Photographer

Infographics by Erica Simek Sloniker, Visual Communications

Stormwater sneaks up on the Seattle region so innocently, as rain droplets falling through the misty air. Yet when it hits the ground, it picks up bacteria from lawn fertilizers, copper from break pad deposits, oil and other pollutants that become deadly to salmon and Orcas in Puget Sound.

The Washington Department of Ecology calls it the biggest water pollution problem in the entire state, and yet lacks a comprehensive plan to tackle the problem.

That’s why the annual Green Infrastructure Summit each February is so exciting. This event, co-hosted by The Nature Conservancy, brings together key stakeholders to begin a discussion that will lead to collaboration for years to come.

Here, government, non-profit, business and research organizations will share what they’ve done already. There have been some great strides made. Green infrastructure such as rain gardens, which keep stormwater from trickling into places it doesn’t belong, have been installed around the city. However, there simply aren’t enough of them.

“We have to move beyond projects that are just another cute street, to tackle this problem on a scale thatwill make a difference to all of Puget Sound,” said Jessie Israel, Puget Sound Conservation Director for the Conservancy.

Stormwater pollutes the marine environment, leaving devastating impacts in its wake. A study flagged up by the Seattle Times recently said stormwater runoff can kill adult fish in as little as 2.5 hours. (Watch the Conservancy's video on this extraordinary research)

Stats like these are why The Nature Conservancy has laid out big goals for tackling this problem. In five years, here’s what we want to see:

- 1 billion gallons of stormwater treated using green infrastructure

- 1 million trees planted or maintained to impact freshwater quality, sequester carbon and benefit underserved communities

- 20,000 new raingardens in private spaces

- Green spaces created and enhanced in ways that better quality of life

- Cross sector, issue, and jurisdictional leaders deploy effective leadership and focus investments in green stormwater infrastructure

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK IN CITIES

Ellsworth Rain Garden Project

Written and Photographed by Tricia Sears, Julian Lawrence, and Megan Fishpool

We have volunteered for The Nature Conservancy, doing projects on the Ellsworth Preserve, for five years. Therefore, we are very familiar with the frequency and intensity of the rain in this area. Ellsworth Preserve is a thriving and beautiful landscape - logged and reforested over many years. There is a small building on a hill at the elevation of 800 ft. that receives over 100 inches of rain per year. The large amounts of rain in this area can cause erosion. To help alleviate erosion problems, we wanted to provide a better method for water to infiltrate into the soil. Being familiar with rain gardens, we were inspired to construct a rain garden by the small building.

Over the course of four days in October and November 2015, we dug the 15 ft. x 6 ft. rain garden out. We then installed small and large well rooted plants so the rain garden would be immediately functional. The plants, known as the common rush or Juncus effusus, were transplanted into the rain garden from an area adjacent to the small building. We also planted one sitka spruce, Picea sitchensis, in the rain garden. The small building has a water tank and its overflow is now directed to the rain garden using old gutters stabilized by strong support branches and cairn style rocks. Since we constructed the rain garden in heavy rain, the immediate effectiveness of the rain garden was clearly demonstrated as it quickly handled large amounts of water!