New research reveals the perspectives of fishing communities in Washington, Oregon, and California and connects it to data-driven science on climate risk, providing the strongest foundation for developing plans that ensure the resilience of fishing communities.

This 'Trash' Tastes Amazing!

A Message from the Sea

"I need the sea because it teaches me…

I move in the university of waves…

It’s ceaseless wind, water and sand…

I became part of its pure movement."

(from Pablo Neruda's The Sea)

Written by Phil Levin, Conservancy Lead Scientist

I first read Pablo Neruda’s poem The Sea as a graduate student while working on Appledore Island – a little island one mile long and one-half mile wide, ten miles off the coast of southern Maine. It was one of those perfect stormy, gray days that was amazing to watch, but much less fun to be out in a small boat doing research.

Looking out at the swell rolling in across the Atlantic, Naruda’s words were etched in my mind. Neruda captures so well a feeling of motion that anyone of us who spends time around the ocean experiences. The tides ebb and flow, waves slap ashore, and currents stream by. But its more than that – the sea’s animals are in motion too. Salmon that began their life hundreds of miles inland swim past us on their thousands-of-miles journey through the Pacific. Humpback whales, which we are seeing in the Pacific in ever-increasing numbers, can travel more than 13,000 miles in a year. And Steller sea lions make phenomenal dives to depths of up to 1,500 feet to feed, staying underwater for as long as 16 minutes.

A few years ago a 14 foot pregnant six-gill shark washed up dead in South Puget Sound. My team from NOAA took samples from the animal and found that its tissues were laced with a form of the pesticide DDT that we know was used only in California more than 40 years ago. Pesticide that a farmer had sprayed decades ago on a field 1,000 miles away had just washed up on a beach only a few miles from my Seattle home.

The ceaseless movement of water and animals connects us. It connects land and sea, sun-drenched shallows and dark ocean depths, distant continents and even time.

But as much as the ocean is about movement, we also turn to the sea for a sense of stillness. And stillness, it turns out, characterizes the lives of many of Puget Sound’s fishes.

Some of you may know one of my favorite fish: the lingcod. Besides being delicious, they are an important top predator in Puget Sound; on average, only killer whales are higher on the food chain in Puget Sound. But what else do we know about them? For properly managed fisheries, it is essential to know where fish live, what habitats they use and how far they travel.

To get at this, NOAA captured fish and inserted tiny transmitters into their bodies. We could then track their movement day and night for months. We were amazed to learn that they hardly move – if they lived on a football field, their whole life would take place in the red zone of a football field between the 20 yard line and the goal line. A full-grown lingcod is half the size of a full-grown human; imagine if you spent your entire life – working, meeting friends, finding food, eating, everything – in an area the size of half a football field.

This isn’t something that is unique for lingcod. The same is true for many fish, including yelloweye rockfish and bocaccio rockfish that live right here in Puget Sound – and are on now the Endangered Species list. In fact, when we look at fish overall, we see that, despite some fabulous exceptions like salmon, fish have the smallest home ranges for their size of any vertebrate animal. A raccoon in the city has a home range of about 28 football fields, or 140 times the home range of a similarly sized lingcod.

Why does this matter? In the early 1980s, rockfish were not really fished commercially in Puget Sound, and some fisheries managers thought they would be a great resource to exploit. Rockfish are a mild, tasty fish and they quickly became popular. The rockfish fishery boomed – you could even see an explosion of rockfish recipes in locally published cookbooks. But fisheries managers didn’t know that rockfish do not move much, and they did not know they grow slowly, mature late and have long lives (yelloweye rockfish can live for 200 years!). All this means that rockfish are easily overfished. About ten years after the Puget Sound fishery boomed, it was shut down. After ten more years, three Puget Sound rockfishes were on the Endangered Species list.

So, many fish basically stay home their whole lives. These fish can’t escape the effects our activities have on their homes.

New brain research is showing that our brains are hardwired to react positively to the ocean, and that being near it can calm and increase innovation and insight. It’s not surprising, then, nearly three billion people globally live within 60 miles of a coast, or that population growth along coasts is six times greater than inland areas.

As more and more people come to the shore to seek solitude and inspiration, we must let the sea teach us. Let it remind us that we are connected – that how we act transcends space and time. And for animals that can’t just get up and relocate, the consequences of our actions can be dire or provide solutions that make our piece of the world a better place.

Learn more about our Ocean Work

Cleaning Up Oceans of Debris

Written by Kara Cardinal, Marine Projects Manager

Photographed by David Ryan, Field Forester

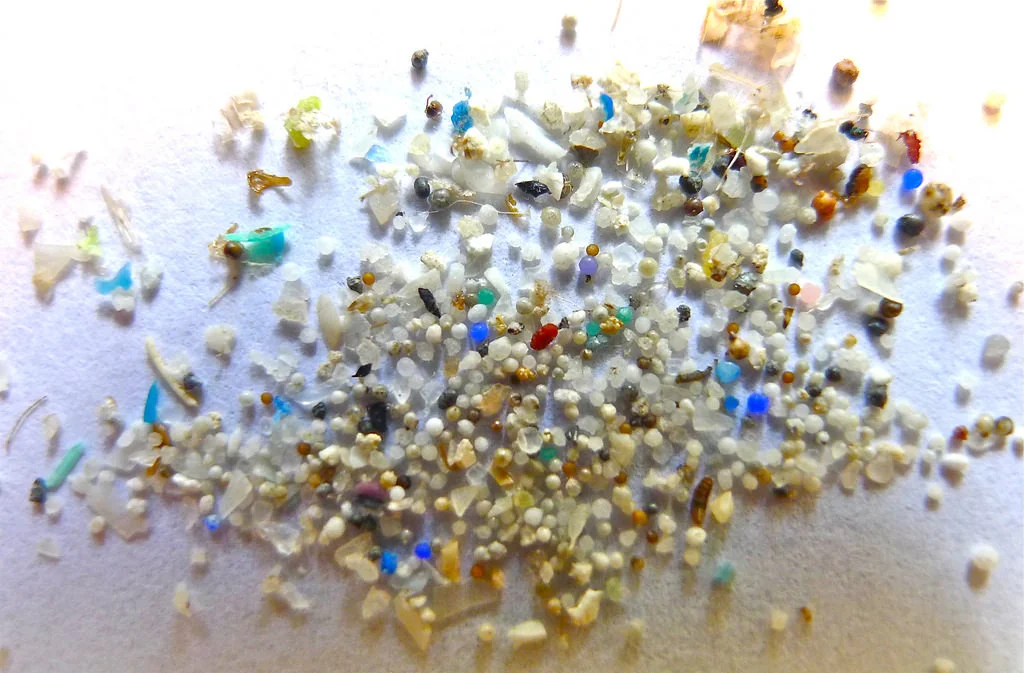

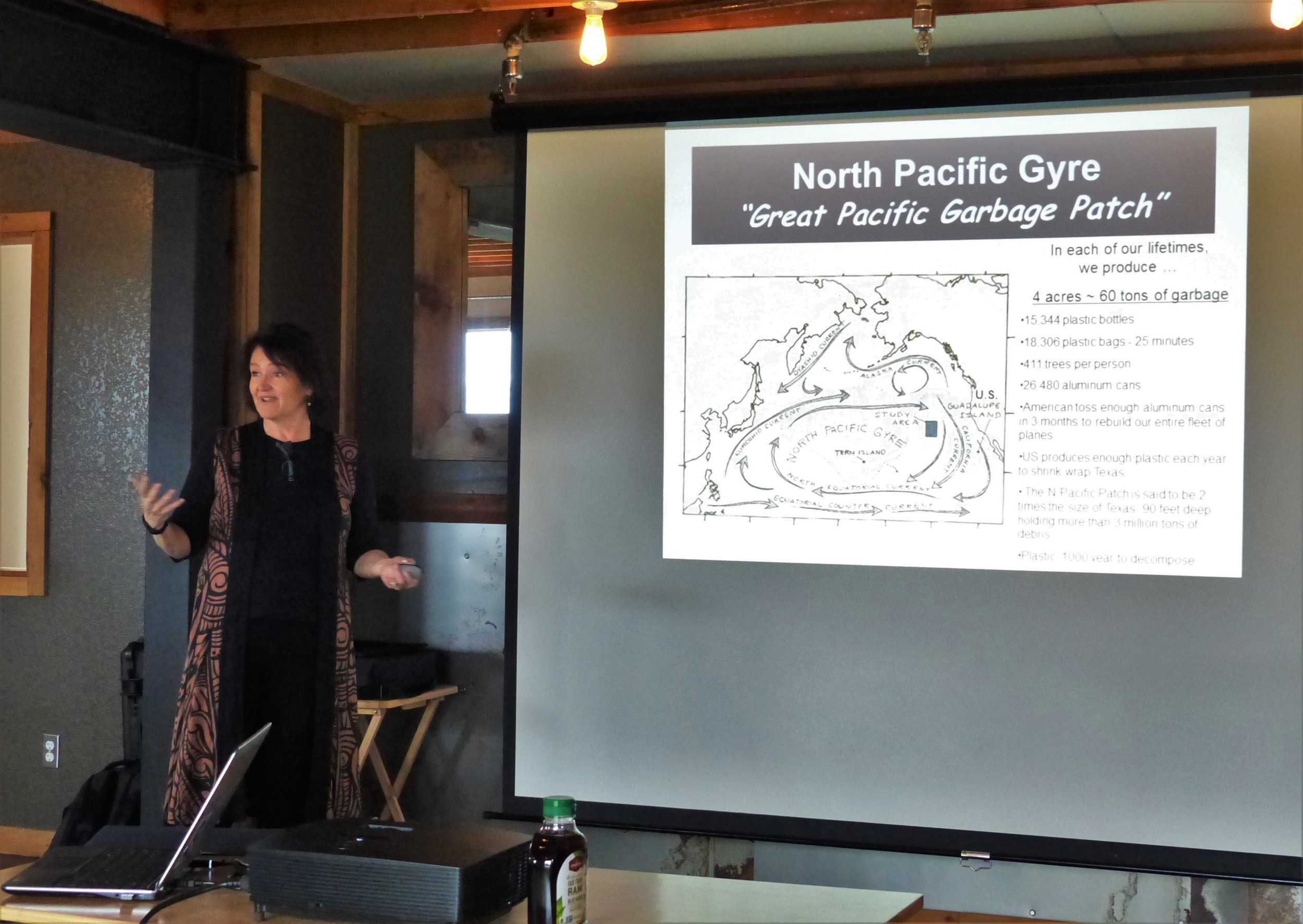

Marine debris - plastics, metals, rubber, paper, textiles, derelict fishing gear, vessels, and other lost or discarded items that enter the marine environment – is becoming one of the most widespread pollution problems facing our world oceans.

Marine life, such as sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals, are increasingly confusing it with food and ingesting plastics and other debris. It can damage important marine habitat. Derelict nets, ropes, line, and other fishing gear can lead to whale entanglements, vessel damage and navigational hazards. Not to mention, who wants to walk down the beautiful Washington coast only to stumble across rafts of Styrofoam, plastic bottles and grocery bags? No part of our world is left untouched by debris and its impacts.

“She may be small, but she is fierce.”

As overwhelming as this problem seems, incredible work is happening right here in Washington to clean up our local oceans.

I had the opportunity recently to join a group of dedicated individuals in Long Beach, Washington who are working to address marine debris issues in our state, as well as recognize the 10-year anniversary of the NOAA Marine Debris Program and the five-year commemoration of the tsunami that struck Japan and resulted in vast amounts of debris from across the world washing up on our local beaches.

This event brought together local volunteers (Grassroots Garbage Gang), NGOs, tribes, state agencies and NOAA officials to share and recognize our work. The event on April 8 kicked off with inspiring remarks from Dr. Kathryn Sullivan, Undersecretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and NOAA Administrator , who was eager to learn about our work and explore our local beaches.

Congresswomen Jaime Herrera-Beutler, with family in tow, also addressed the crowd. Referring to the community efforts on the Washington coast, she recited a quote from her daughter’s bedroom wall: “She may be small, but she is fierce.” These words couldn’t be more true – folks on the Washington coast are doing local-scale work with a global-scale impact.

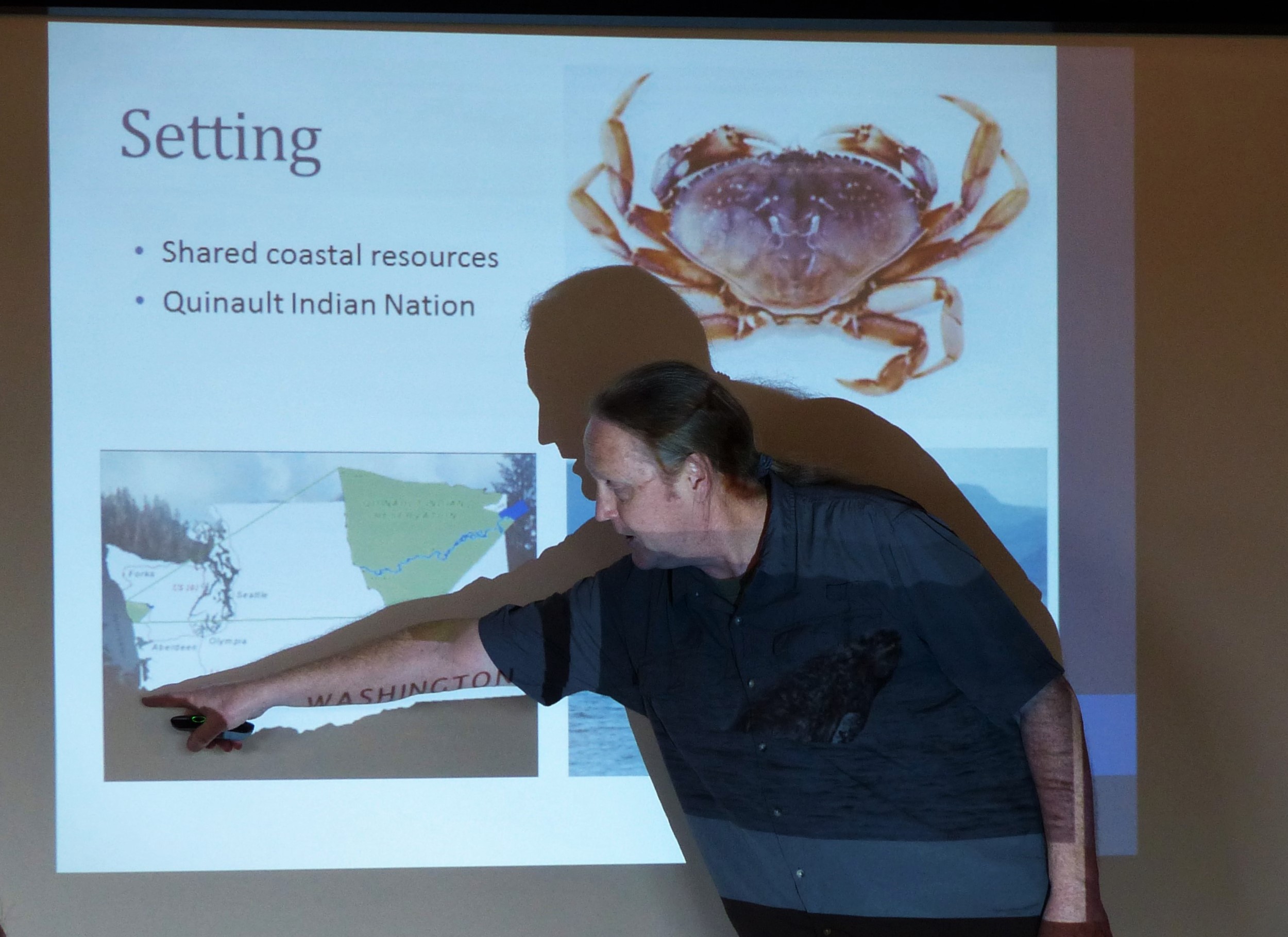

At The Nature Conservancy, we are doing our part by addressing the issue of derelict fishing gear along Washington’s rugged coast. With funding from NOAA and in partnership with the Quinault Indian Nation and Natural Resource Consultants, we have removed over 500 pots, lines, and buoys from the Washington Coast. The main goals of this project can be summed up by 1) getting derelict gear out of the water, 2) keeping gear out of the water through a sustainable recovery program, and 3) doing outreach to tribal fishermen and the surrounding communities about the habitat, economic and safety issues of derelict fishing gear.

See our recent blog post on this project.

Before I started my long journey home, I decided to take one last walk along the beautiful beaches of the Long Beach Peninsula. As I was walking out towards the water, who did I see coming off the beach lugging a big bag full of trash? None other than Dr. Kathryn Sullivan herself! I went up to shake her hand and thank her for visiting our special corner of the country. She remarked “I couldn’t travel all this way and not do my part.” I smiled to myself as I continued my walk along the waters edged and felt very confident that all of us together might just make a difference in this world.

NOAA’s Marine Debris Program

Grassroots Garbage Gang

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK IN OCEANS

Washington Trustee John Rose receives Oak Leaf Award

Champion for Eastern Washington Forests and Conservation across the state

John Rose is passionate about Washington’s great outdoors. It’s a passion that he has carried his whole life, has fostered in his family, and celebrates with his friends. The Evergreen State’s signature landscapes have been the backdrop for some of the most exciting and momentous times in John’s life – from childhood trips in the San Juan Islands, to exploring forests of the Cascades, to courting his wife, Patty in the fragrant sage desert of central Washington. John cares about maintaining our state’s beauty and health for all who live here. But there is one thing that John cares about even more than the great places of Washington and the Northwest- conserving those places for future generations.

John’s commitment to conservation here and around the world was honored this week at a global gathering of trustees where John was recognized with the Oak Leaf Award for his tireless leadership and hard work.

A member of The Nature Conservancy since 1975, John has served on the Board of Trustees of the Washington Chapter since 2000. During that time, has been Board Chair as well as chaired the Board’s Philanthropy, Nominating & Governance, Executive, Campaign and Conservations Committees.

John is a leader amongst our trustees and an anchor of the Board. He has a deep understanding of the Conservancy’s work and is relied upon by his fellow trustees to bring a balanced, insightful and probing perspective to our work. He deeply supports the staff. He works indefatigably on our behalf. He has an infectious passion for our work and the people with whom we work. And he has backed up his passion and his work with major philanthropic commitments.

A thought leader for the Conservancy, John has led the Board in moving from a preserve and Washington focus to an embrace of our global mission and the role of the Chapter in advancing our Global Challenges/Global Solutions approach. He has traveled to Central America and across the Pacific Northwest and Canada to learn about our work. He has galvanized Board support and engagement in our next-generation projects such as marine fisheries conservation and the Emerald Edge as well as large-scale forest conservation and restoration in the Cascades.

John’s tangible, lasting contributions to our mission, to the region and to the Chapter are extraordinary. John has demonstrated a remarkable ability to inspire giving in others. John is the kind of trustee that enables us to change the world.

It is a sign of John and his wife Patty’s exemplary leadership and their deep commitment that receiving the Oak Leaf Award is not only a highlight for them, but also a moving and joyous moment for all of us at the Washington Chapter.