Dazzling, dramatic and iconic, the 27 glaciers cloaking Mount Rainier add much more to the Pacific Northwest than just scenery.

In fact, their importance runs as deep as our rivers. Mount Rainier’s glaciers, and hundreds more in the Cascades and Olympics, are unsurpassed as natural water storage and delivery systems. As neatly as a natural tap, glaciers dispense meltwater when we need it the most, during the hot days of late summer. That melt provides critical freshwater for drinking and agriculture and supports habitat for keystone species like salmon.

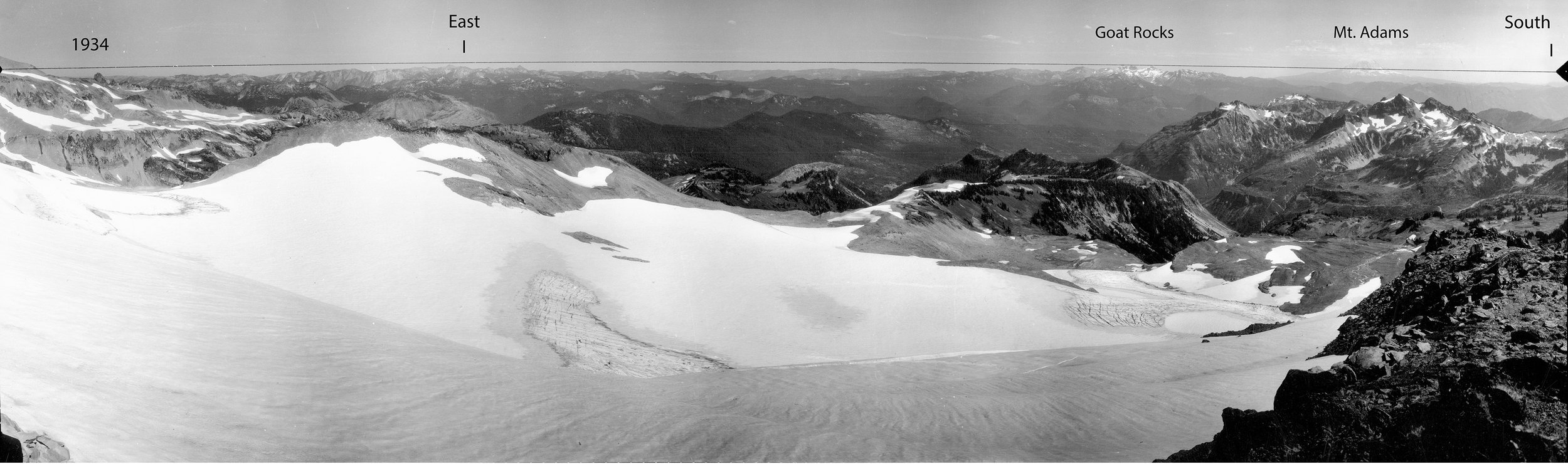

Move the slider above to reveal dramatic glacier loss between 1934 and 2017 at Sugarloaf Rock on Mount Rainier. Historic image by George B. Clisby for the U.S. Forest Service, provided courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Contemporary image by John F. Marshall for The Nature Conservancy. Keep reading for information on this photo comparison and to view others.

The Latest News on Climate

Glaciers are also stunning centerpieces of the region’s famed scenic and recreational riches. “Humans are drawn to glaciers’ beauty, to the interplay of light and water,” says Jon Riedel, geologist with the National Park Service. “They are a source of inspiration.”

Riedel should know. For decades, he has trekked into remote glaciers in Olympic, Mount Rainier and North Cascades national parks to study them. He’s braved crevasses, measured annual melt and accumulation and analyzed LIDAR imagery to monitor glacial volume.

Despite the beauty and inspiration he finds, Riedel’s work has also brought him face to face with a discouraging truth: Our glaciers are shrinking, and fast.

Going, Going … Gone

“The system is complex but the signals are clear,” Riedel told a concerned audience in January. “Losses are pretty staggering in the last 50 years.”

As climate warms and precipitation patterns shift from more snow to more rain, with longer and warmer summers, glaciers suffer a double whammy, explains Riedel. They melt more in the summer and gain less snow in the winter. The balance tips, and glaciers shrink dramatically.

From 1971 to 2006, he says, Mount Rainier lost 14 percent of its glacier cover. North Cascades National Park has seen 20 percent loss of glacier area from 1971 to 2006. And the Olympic Mountains have seen a staggering 43 percent of their glacier cover disappear since 1982.

These changes are starkly shown in image sets from Mount Rainier, which pair late season photos taken early in the 20th century with photos taken from the same locations by photographer John Marshall in last fall.

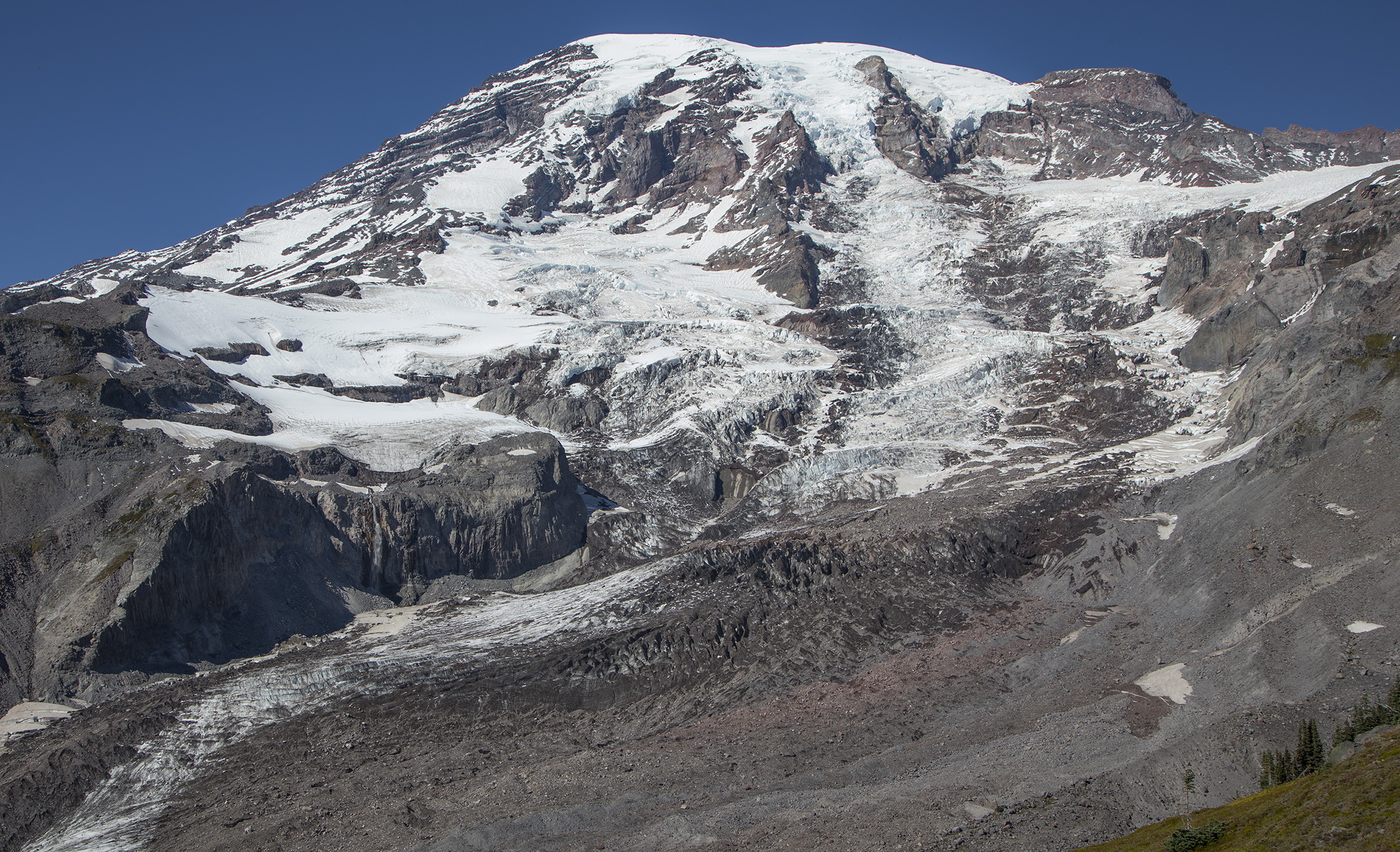

Move the slider to reveal dramatic losses on the Nisqually Glacier. Historic image (1910) by Francois Matthes; provided by University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections (UW39009). Contemporary image (2017) by John F. Marshall for The Nature Conservancy.

Riedel notes how each image set captures different geologic aspects of the changes. “I’m struck by how much the lower part of the glacier has thinned and narrowed since 1910,” he says of the Nisqually Glacier images (above). Shown on left, he adds, “A pretty large mass of the Wilson glacier is now broken in two by a newly exposed outcrop.”

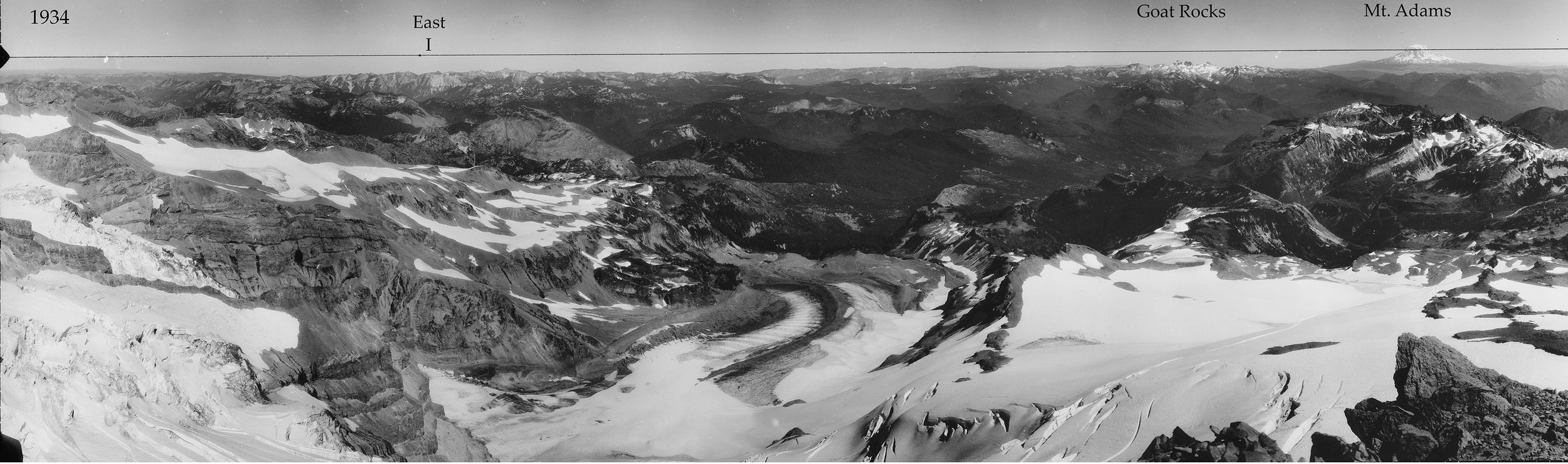

Move the slider to reveal dramatic glacier loss at Sugarloaf Rock. Historic image by George B. Clisby (1934) for the U.S. Forest Service, provided courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Contemporary image by John F. Marshall (2017) for The Nature Conservancy.

The Sugarloaf Rock photos (above) illustrate how lower elevation glaciers that are not connected to the summit are being lost more rapidly than glaciers higher on the mountain. “The large expanses of bare rock and rubble attest to the rapidity of the ice retreat,” says Riedel.

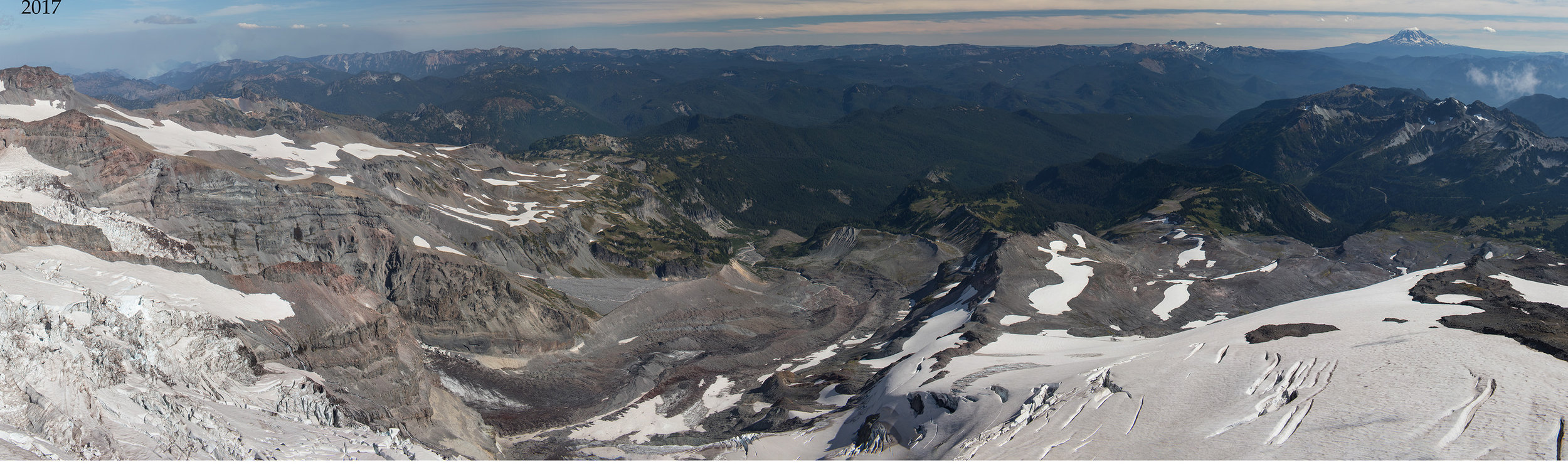

Move the slider to reveal glacier loss at Anvil Rock. Historic image by Reino R. Sarlin (1934) for the U.S. Forest Service, provided courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Contemporary image by John F. Marshall (2017) for The Nature Conservancy.

The view from Anvil Rock (above), just below Camp Muir, shows several interesting changes, he says. For example, the rubbly moraines that were once transported on top of the glacier are now seen as low, crescent-shaped ridges that rest directly on the ground.

Taken together, Riedel says the changes captured are both poignant and telling. “Glaciers remind us of our past, but give perspective on our future.”

Sentinels of Change

What will happen as Washington’s glaciers disappear? River volumes are already impacted, says Riedel. Just 30 years ago, for example, glacial melt accounted for up to 18 percent of the water in the Skagit River. Now, it’s just 10 to 12 percent — a 24 percent decline. The White River at Mount Rainier and other glacial-fed rivers have seen similar declines.

This trickle-down effect has ecologists like The Nature Conservancy’s Julie Morse concerned. “In unregulated watersheds, there really is no backup storage. Glaciers are the critical water source in spring and summer for many of our watersheds in Western Washington,” says Morse. “The loss of glaciers and snowpack will impact everything, from having enough water to irrigate crops in the summer, to even having enough water in rivers and tributaries for salmon populations.” What’s more, she adds, resulting warmer-stream temperatures could rise above the threshold for salmon.

Heidi Roop is a scientist and communicator with the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington. Roop believes that the inspiring beauty of glaciers, along with views of their demise, have a power that sparks people into action far more than abstract facts and figures. “You don’t have to understand the physics to see that something is different,” she says. “Glaciers are powerful and compelling sentinels of climate change.”