by Grace Lee Kang, Freelance Writer

When Jamie Robertson and his wife moved into their house in Tacoma, the pair of bigleaf maples residing in the front yard welcomed them to their new home. Nearly 75 feet in height, the trees’ branches and foliage soared high and wide, providing shade and cooler temperatures all afternoon to the home and its residents.

But then several years ago, Robertson, a geographer at The Nature Conservancy, started to notice a change in the trees’ health. He recalled, “If we had set up a timelapse, you could have seen the damage move from one side of the tree to the other in an eerie way—with dead brown leaves on one side and vibrant, green foliage on the other.” Ultimately, the tree declined enough to require removal.

Reports of dying and dead bigleaf maples, a native Washington species, have puzzled experts for years. And there were no clear answers to the distinctive trees’ decline until recently, when a study led by the University of Washington found that bigleaf maple die-off is linked to hotter, drier summers as well as urban development. The extreme conditions weaken the tree’s immune system, leaving it vulnerable to other stressors and diseases.

The majestic maple that presided over Robertson’s home represents a larger loss beyond a single home or moment in time. Trees planted in urban areas help our cities function more like forests — reducing the effects of polluted stormwater and air temperature, and supporting human health and well-being. With greater tree canopy density, research shows urban communities can experience better long-term health with less asthma, strokes, and cardiac arrests.

360 Video [Click and drag to move around]: Ride through a North Tacoma Neighborhood. Big leaf maples and other trees provide shade and cooler temperatures all afternoon to residents of this neighborhood. Credit: Erica Sloniker/TNC

Yet Tacoma is just one of countless cities across the country where systemic racism and decades of racist housing and development policies like redlining are associated with low tree canopy coverage in communities of color.

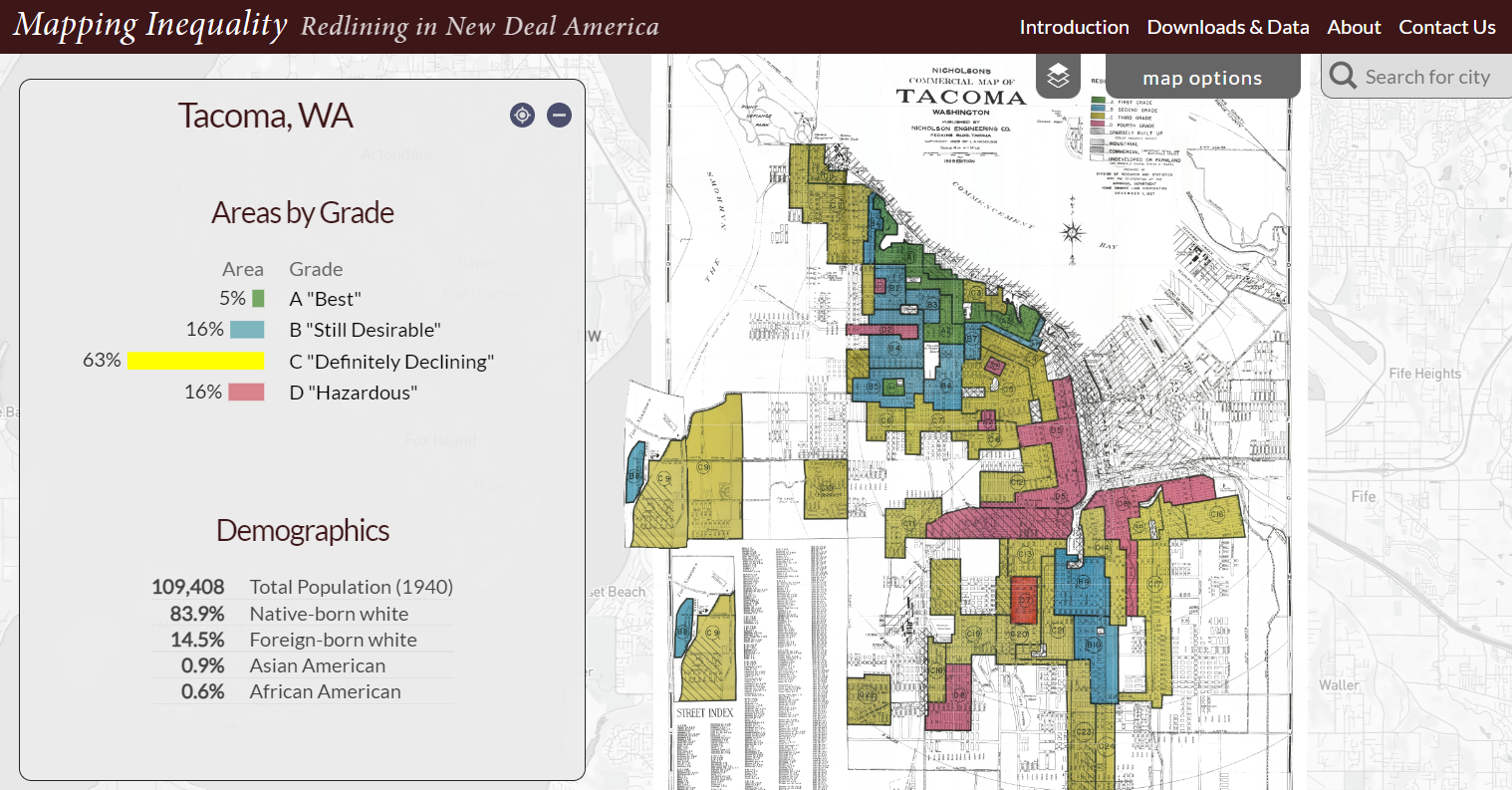

This Tacoma map created by agents of the federal government's Home Owners' Loan Corporation between 1935 and 1940, assigned grades to residential neighborhoods based on the race of residents. Neighborhoods receiving the highest grade of "A"—colored green on the maps—were deemed minimal risks for banks and other mortgage lenders when they were determining who should receive loans and which areas in the city were safe investments. Those receiving the lowest grade of "D," colored red, were considered "hazardous." Click on the image to see an interactive map. Credit: Mapping Inequality - Redlining in New Deal America.

Today, the Tacoma Mall neighborhood has 10% tree canopy cover — among the lowest percentages in the city, and half the city’s average. Areas with low canopy coverage are significantly more at risk from extreme heat and experience lower levels of air and water quality.

The Tacoma Mall neighborhood is the focus area for Greening Research in Tacoma (G.R.I.T). Credit: Erica Sloniker/TNC

And with a disproportionate distribution of trees, the energy savings and cooling effects aren’t equal in every neighborhood. For instance, if you live in a historically redlined area, you have to pay more to achieve the same level of cooling than those in traditionally white, wealthier neighborhoods.

360 Video [Click and drag to move around]: Ride through a Tacoma Mall Neighborhood. With ten percent tree coverage, this neighborhood has one of the lowest tree canopy covers in Tacoma—a city itself that has some of the lowest canopy cover in the Puget Sound region. Credit: Erica Sloniker/TNC

Against this backdrop, the City of Tacoma, Tacoma Tree Foundation, and The Nature Conservancy have been investing in community engagement and greening measures like art installations, tree plantings, and additional green infrastructure. Greening Research in Tacoma (GRIT) builds on this work as a research project bringing together these organizations, with the Environment & Well-Being Lab at the University of Washington and funding from Puget Sound Partnership, to better understand how these initiatives impact the South Tacoma neighborhood and the ways in which human well-being and green infrastructure intersect.

To date, most research in this field is correlative and macro in scale, using remote sensing or satellite data to look at tree cover and comparing that with census data — leaving us with an incomplete picture of what’s happening within a community. GRIT is a collaborative and quantitative effort seeking to address the lack of on-the-ground data through different ways, including: monitoring temperature before, during, and after green infrastructure installation; learning from residents about their experiences with tree plantings and vision for the community; and building community-led science projects.

Alejandro Fernandez (left) with the Tacoma Tree Foundation and Dr. Ailene Ettinger (right) with The Nature Conservancy participate in a tree giveaway for residents. Credit: Hannah Letinich

As a quantitative ecologist with The Nature Conservancy, Dr. Ailene Ettinger is one of the GRIT team members working to assess the environmental and social effects of greening efforts in South Tacoma. She explains,

“There’s a real need to understand how the communities affected by systemic inequities, like redlining or discriminatory urban planning, experience changes. It’s only with fine-scale data from within the communities themselves that we can start to answer questions like: When we plant trees, how do people experience that? How did the benefits reach them, if at all? How does it feel to be in that neighborhood before and after a greening installation takes place?”

Currently, Dr. Ettinger is working on measuring environmental effects by installing temperature loggers (also known as temperature sensors) on utility poles throughout the South Tacoma neighborhood. Monitoring the air temperature in various areas will help determine what effects tree planting has, including larger trees established two or more years ago, on nearly a block by block level. Reflecting on her time in the field, Dr. Ettinger appreciates the chance to engage with people walking by who are curious about what she’s doing on the local utility poles.

“Residents often stop and ask what’s going on, and I also get to hear about trees that are important to them — like a postal service worker I often see who shared how much he appreciates the shade when he’s delivering mail on a hot day.”

For Alejandro Fernandez, building relationships in South Tacoma, where he lives and works, is a critical way to understand what’s also happening on a human level. As Community Partnerships Coordinator at the Tacoma Tree Foundation, Fernandez has gotten to know and hear peoples’ perspectives through community events like educational tree walks, tree giveaways, and tree plantings.

Alejandro Fernandez, Community Partnerships Coordinator at the Tacoma Tree Foundation, helps distribute trees to residents as part of a tree giveaway to encourage tree planting. Credit: Hannah Letinich

One of the biggest challenges Fernandez has seen through his work is the sheer amount of care and commitment it takes to maintain new tree plantings and help them grow to maturity. He cautions,

“You can plant a tree, but you’re also battling climate change and its extreme temperatures. If you miss a couple of days of watering during a hot week, you can come back to a tree that’s stressed and may end up dying.”

And a healthy tree canopy depends on mature trees.

“US Forest Service research shows that healthy, long-lived shade trees provide the maximum benefit to people and wildlife at maturity, roughly between 30-60 years of age. We need to protect the trees we already have, and make sure new tree plantings are done thoughtfully to promote healthy urban tree canopy for the long-term future.”

The tree giveaways and plantings are just the beginning, which makes the Tacoma Tree Foundation’s on-the-ground work within the community a vital foundation for long-term success. From free training to become a Tree Steward advocate to family-friendly nature walks, the organization’s programming engages community members where they are. To Fernandez, the most exciting part of his job is the response from his fellow residents.

“Whether it’s going door to door to see who’s interested in hosting a tree or delivering them to homes and planting them the right way, it’s nice to see the energy given back to us from the community.”

Since GRIT kicked off in late 2021, the collective effort and data from the partner organizations has already begun to deepen our understanding of how greening initiatives affect people and communities. As the project progresses, the research will continue to generate new ideas about how we can plan and invest in greening our neighborhoods, cities, and states — with more equitable and effective results for people everywhere.