This blog is condensed from the original posted on the University of Washington’s website.

Similar to how children learn, often unconsciously, to mimic the adults around them, a small, silvery ocean fish aiming to reproduce follow a strategy that scientists call “go with the older fish.” As juveniles, herring join large schools offshore to mingle, eat and grow. Then younger, smaller herring follow the older, more experienced fish back to specific beaches to spawn.

Herring roe are an important resource for many coastal tribes. The Sitka Tribe collects them on branches of native evergreens. Photo by Phil Levin.

Herring migration isn’t random, and this could explain why herring have been missing for years from some beaches, even in the few cases where the overall population numbers are adequate. If older fish that spawned at a specific beach are wiped out, there are no fish to lead the next generation to use that particular site.

These new findings could entirely change how Pacific herring are managed, and aid in restoring some of the spawning populations now absent from many of the beaches along the west coast of British Columbia and Alaska.

“The herring are very important to our people,” said Harvey Kitka, an elder and former tribal council member with the Sitka Tribe of Alaska. “Spawning was a huge event each spring, and probably for thousands of years herring spawned in the same area in Sitka Sound.”

The Ocean Modeling Forum — a collaborative, interdisciplinary effort that applies modeling to tackle ocean issues — kicked off its herring project in June 2015 with a summit in British Columbia. The summit convened a number of stakeholders, tribes and First Nations to discuss the role herring plays socially and ecologically, and to begin to develop a framework for how different approaches and knowledge — including traditional ecological knowledge — can be used in fisheries management practices.

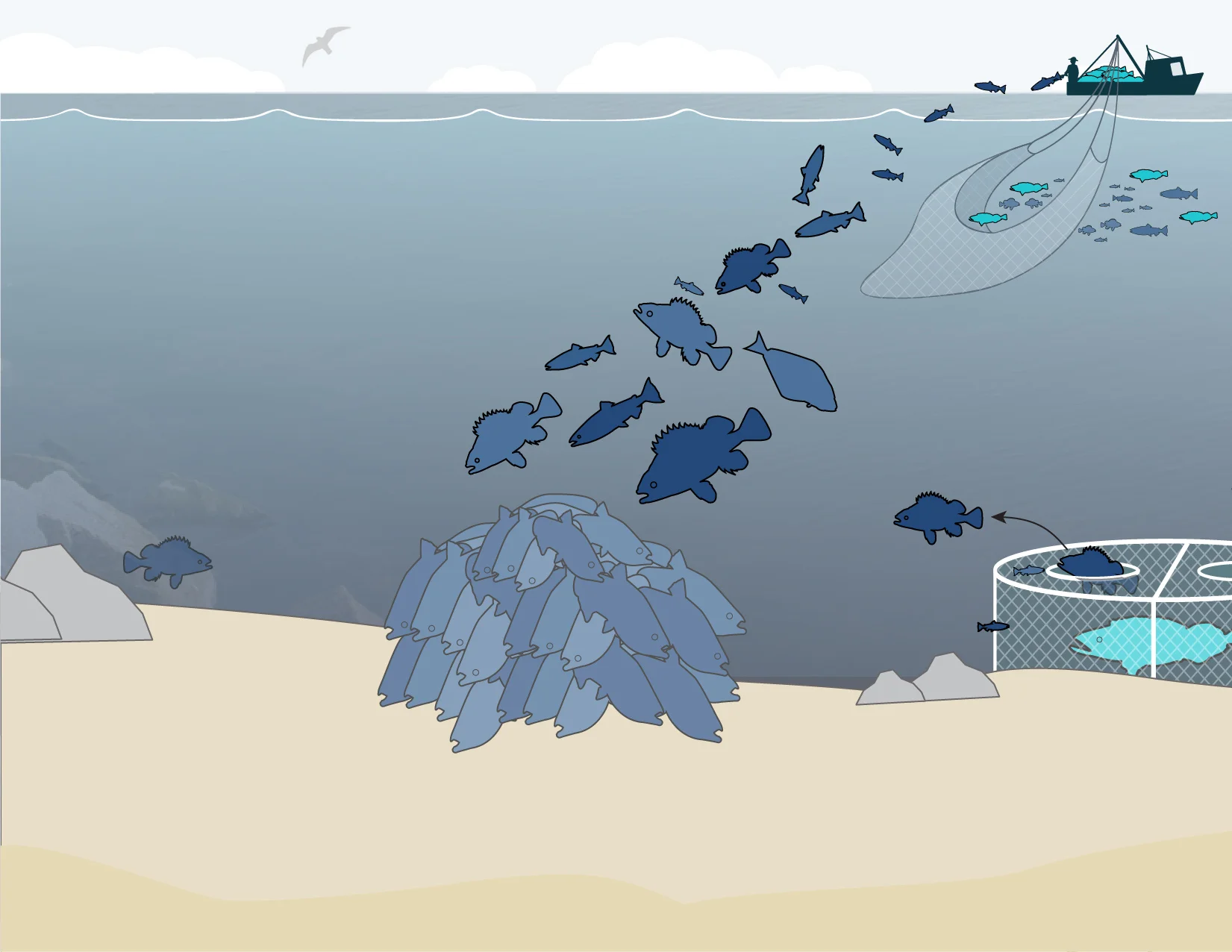

A visual representation of the perspectives on herring presented during the Ocean Modeling Forum’s kickoff summit. Image courtesy of Sam Bradd.

“During our conversations, it became very clear that herring and humans are really tightly coupled, and that’s true whether you’re a commercial fisherman, a vessel owner or a traditional harvester,” said Tessa Francis, managing director of the Ocean Modeling Forum and lead ecosystem ecologist with the Puget Sound Institute at UW Tacoma. “This was an opportunity for us to think about different forms of knowledge and alternative models in a situation related to fishery management.”

“Herring used to be the life force of the indigenous villages in the spring,” said Phillip Levin, co-director of the initiative who also holds a joint role as a UW professor of practice and lead scientist with the Nature Conservancy of Washington. “For herring management to be successful, it must address problems at the scale that impacts the well-being of the people who depend on the fish.”

Visit UW’s website to learn more about this research and collaboration.