Writer Owen Oliver travels to the Ellsworth Creek Preserve for the first time, the Indigenous territory of his people, the Willapa Band of the Chinook Indian Nation. Travel with him through old-growth cedar and Sitka spruce and learn what these lands and waters mean to the Chinook.

Climate Clues in Washington's Coastal Old-Growth Forest

The 'cutting edge' of forestry practices

Writing and photos by Ryan Haugo, forest ecologist

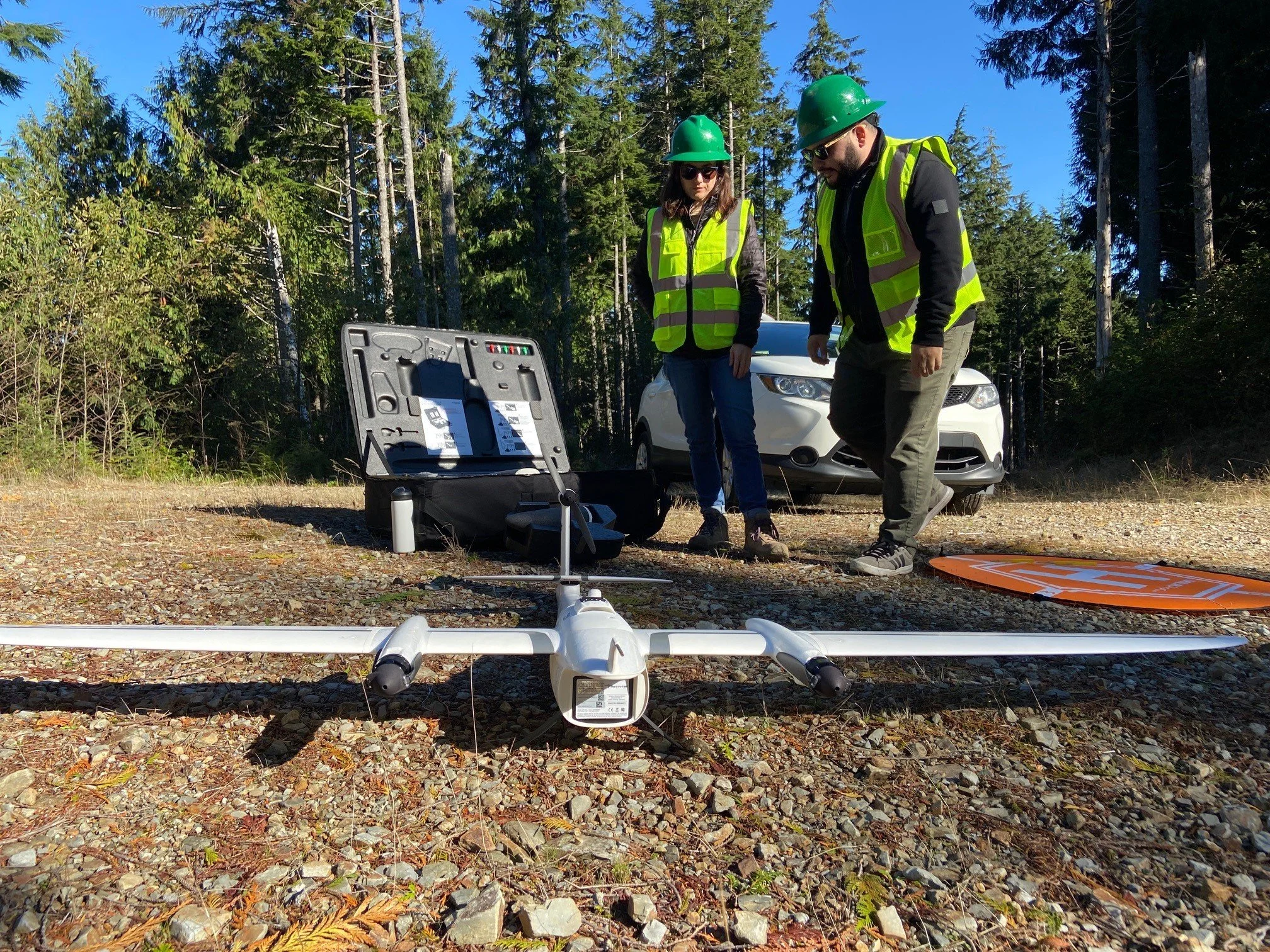

On a misty December morning, an esteemed group of forest ecologists from across the Pacific Northwest met with our staff along the shores of Willapa Bay to talk science and restoration. This group had driven through dark morning hours in order to spend the day tromping around the forest and building and strengthening science partnerships, while gaining a first-hand experience with The Conservancy’s “Ellsworth experiment.”

The Ellsworth Preserve is best known for protecting some of the largest remaining stands of coastal old-growth rainforest in southwest Washington. Towering forests of Western red cedar, Sitka spruce, western hemlock and Douglas fir support a number of endangered and threatened species as well as coastal cutthroat trout, chum and coho salmon. However, the preserve doesn’t just protect old-growth forest. In fact, the preserve is predominately young, dense forests that for many decades were heavily harvested for timber. In 2006, we launched the audacious goal of conserving and restoring the ecological integrity of these former industrial forest lands.

At the time, moving from the protection of small preserves to entire watersheds and diving headlong into active forest management was a huge step for The Conservancy. The best available science suggested that forest thinning (logging!) and repair or decommissioning of forest roads would be important tools to aid recovery of coastal watersheds and restore old-growth habitats. However, across the Pacific Northwest coast, there were few examples of full-bore ecological restoration at such a scale. Our Ellsworth experiment applied a rigorous design and an extensive monitoring network to test and evaluate the best approach. Before the first forest treatments began, we conducted detailed measurements of forest structure and vegetation, birds and amphibians and stream habitats to establish a baseline.

Often we describe science as “cutting edge.” This might make it seem that data, the fundamental building block of science, have a limited lifespan and easily spoil if left too long on the counter. Sometimes this is true. But when science is done well, using experiments designed for the long haul, data are more like fine wines that get better with age. Do our original 10-year-old measurements from Ellsworth still have value? Absolutely. Ecosystems change slowly, and our pre-treatment data are just now ready to pair with updated findings on the state of the preserve today.

This will allow us to start answering the fundamental questions of the Ellsworth experiment. But we need to identify creative collaborations and funding opportunities to ensure a return on our investments in healthy forests (consider donating to help continue this work). Through outreach and an open invitation to the science and conservation communities, we hope to foster an extended shelf life for our data. The insights yet to be revealed have the potential to inform future forest restoration within and beyond Ellsworth.

As we concluded the Ellsworth science tour in the early December twilight, our boots were heavy with mud but our spirits were buoyant and enthusiasm was high. The pre-treatment data provide a tremendous foundation. New technologies are emerging to aid in our efforts and exciting new partnerships are on the horizon. The second decade of science at Ellsworth is looking very promising.

Read more about the Ellsworth experiment

Black Bears Roam at Ellsworth Creek

Written & Photographed by Kyle Smith, Field Forester

Late Spring at The Nature Conservancy’s Ellsworth Creek Preserve in Southwest Washington is a magical place for wildlife viewing. Spring rains bring out amphibians in huge numbers such as the tailed frog, ruffed skinned newts, Columbia torrent salamander, pacific giant salamander. In fact, a survey conducted by the Washington Natural Heritage Program and TNC scientists found that Ellsworth Creek had on of the highest populations of amphibians in Washington State. Amphibians aren’t the only things that roam the misty forest floors in Ellsworth Creek.

Black bears come out of their winter torpor to forage on grasses, berries and the fresh sapwood of actively growing trees. Southwest Washington and in particular Ellsworth Creek have some of the largest numbers of black bears in the lower 48. We were lucky to come across these beautiful black bears at the preserve recently!

The huge old growth forests of Ellsworth Creek offer excellent denning sites and the productive soils and over eight feet of annual prescription grow huge thickets of huckleberries, salmon berries and salal berries that bears plump up on all summer long. High among the forested trees tops a small robin sized bird called the marbled murrelet flies in at over 60 mph to nest up in the old growth canopy with in the Ellsworth Creek. These small robin sized birds rare birds spend most of their life at sea but in late spring and early summer they can be seen flying in over Ellsworth Creek to use the large old growth tree branches to nest and raise their young before returning to the sea in late summer. Just off to the west looking down on to Willapa Bay, tens of thousands of dunlins and sandpipers swarm to Willapa Bays pristine waters to feed upon invertebrates with in the mudflats of the Bay.

A Quick Peek at Ellsworth Creek

Written by Jeff Compton, Conservancy staffer and sometime tree hugger

It’s been more than a decade since I first stepped foot in The Nature Conservancy’s Ellsworth Creek Preserve. That first visit was an introduction to an ambitious new project full of promise, challenge and uncertainty. We were talking about owning an entire coastal watershed, not just to protect it, but to use it as a laboratory for forest restoration – a place where we could collaborate on long-term trials that we hoped would deliver far-reaching benefits for nature and people.

But what really captivated many of us then were the serene patches of forest that were home to the few true giants that remained. In select spots above or beside the creek we met massive, ancient Western red cedar and Sitka spruce. We were dwarfed by those awe-inspiring trees, the mightiest of which were older than the Magna Carta.

Over the years I had the privilege of visiting this preserve many times, and always thrilled to spend a few peaceful moments in the tranquil forest with those enduring titans.

After a several year absence, I recently headed to southwest Washington with a group of colleagues and stepped once again into the Ellsworth Creek watershed. I am thrilled to report that the preserve is still there. The restoration work continues. The vision and optimism about our future forests is alive. And those giants still stand – old-growth trees that now feel like old friends.

The Conservancy’s efforts at Ellsworth Creek are about the future and the big picture. But the place offers something personal for me today. I sometimes feel overwhelmed, even intimidated, by the pace of change in my life, my city, my world. I take great comfort in knowing that some things – and some places – remain steadily, beautifully the same.

Scouts & Old Growth

“With 13 boys along there was no shortage of energy and humor.”

BY BOB CAREY, NATURE CONSERVANCY SENIOR PARTNERSHIP DIRECTOR, PUGET SOUND PROGRAM

Thirteen boys. 600 acres. 800 year old trees. Those are the impressive numbers from a weekend backpacking trip to Noisy Creek, along the eastern shore of Baker Lake. Boy Scout troop 4100 camped in the shadows of old-growth forest protected by The Nature Conservancy in 1990.

The conservation of this forest turns out to be a gift that keeps on giving. Amidst spectacular views of Mount Baker and Baker Lake, we walked through trees up to 15 feet in diameter in an area known for prolific owl activity. An adrenaline-infused game of “wolves and rabbits” (a teen-appropriate combination of hide-and-seek and tag) among the towering trees and billowing mosses made these youngsters forget all about their day to day lives and fully enjoy this time away from it all.

A weekend in the old-growth is a great respite from the drum of civilization and the pace of everyday lives packed to the brim with work, school, sports, music, homework. It was wonderful to see boys relax in an environment where they could be themselves. And it’s amazing how comfortable and completely un-bored they were in a place so far from their TV/video screens.

All of this was made possible through the conservation of an old growth forest, set aside for future generations before these boys were even born. What a great reminder of how critical it is that we save these very special natural places for generations to come.