New research out of the Ellsworth Creek Preserve offers insights into how we can accelerate the development of the old-growth traits that help forests persevere through the most severe impacts of climate change.

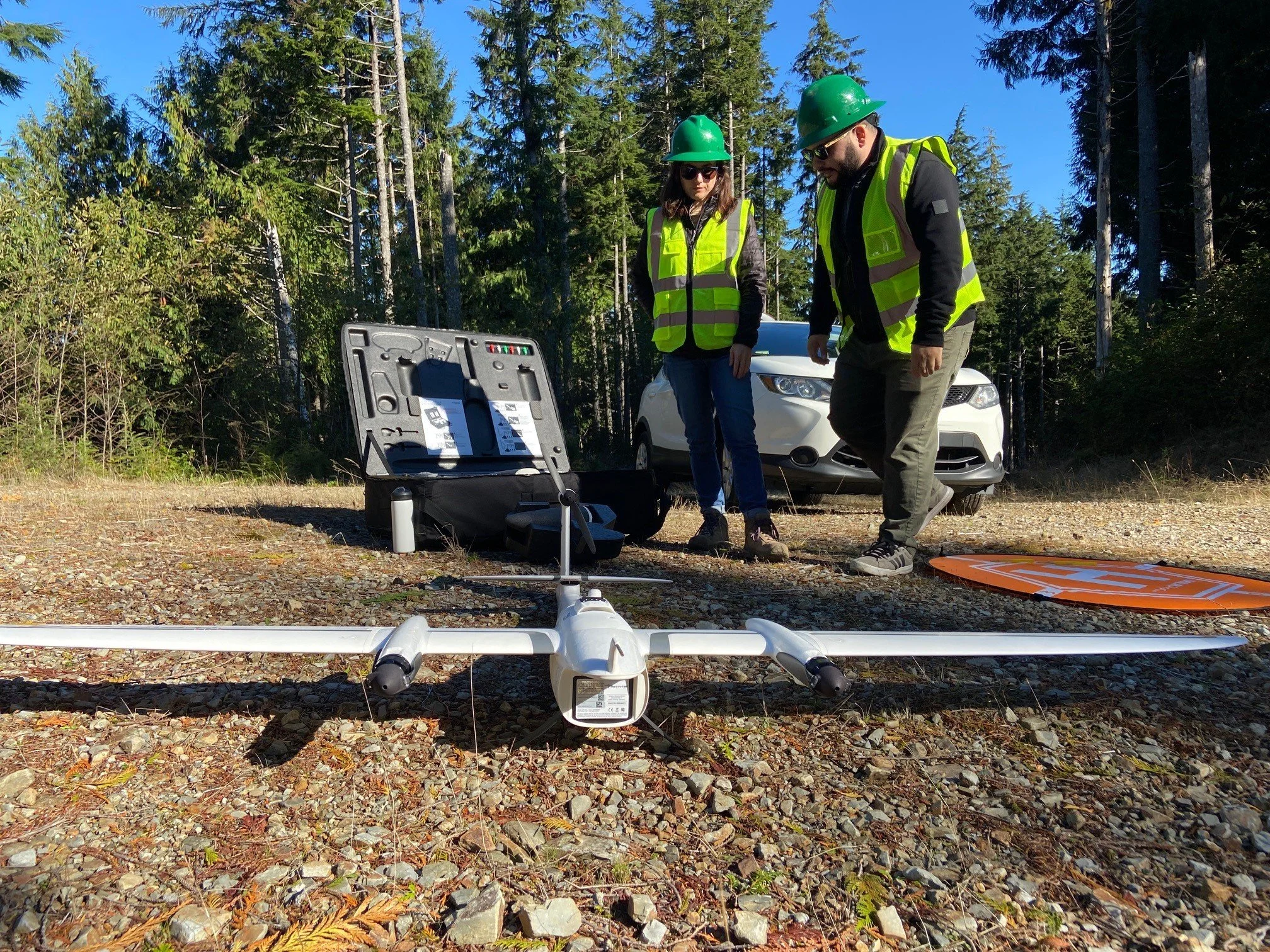

Taking Flight: How Drones Amplify Conservation Efforts

Drones have emerged as a groundbreaking tool extending our reach beyond the limits of human exploration. While many are familiar with seeing the possibilities in adventure photography or package delivery, the use of drones in conservation has become increasingly creative for those both out in the field and in the lab.

Summer Science Interns Find Connection in Conservation

New Seeds on the Block

Drone Saw aids in Drought Research

The Power and Potential of Collaboration for Real-World Results

Catching Animals... on Camera in the Ellsworth Creek Preserve

Science at Home: Environmental DNA & Biodiversity assessments - Small Tools With Big Impacts

Science at Home: Building Climate Resilience at Ellsworth Creek Preserve

Ellsworth Headwaters Protected

A small but significant 80-acre acquisition at our Ellsworth Creek Preserve in southwest Washington protects the headwaters of this 8,000-acre watershed where we’ve been working for more than 20 years.

The new property was harvested about five years ago, leaving our Preserve vulnerable to high winds on its boundary that blew down trees, and sediment runoff into Ellsworth Creek. With the acquisition, made possible by generous private donors, we’ll be able to restore it.

Restoring Old Growth on the Coast—Using Science to Measure Our Success

Salmon Are Bringing the Holiday Cheer to Ellsworth

Hawaii Program takes home lessons from Ellsworth Creek

Showcasing the Importance of NOAA Funding for Salmon Restoration

The 'cutting edge' of forestry practices

Writing and photos by Ryan Haugo, forest ecologist

On a misty December morning, an esteemed group of forest ecologists from across the Pacific Northwest met with our staff along the shores of Willapa Bay to talk science and restoration. This group had driven through dark morning hours in order to spend the day tromping around the forest and building and strengthening science partnerships, while gaining a first-hand experience with The Conservancy’s “Ellsworth experiment.”

The Ellsworth Preserve is best known for protecting some of the largest remaining stands of coastal old-growth rainforest in southwest Washington. Towering forests of Western red cedar, Sitka spruce, western hemlock and Douglas fir support a number of endangered and threatened species as well as coastal cutthroat trout, chum and coho salmon. However, the preserve doesn’t just protect old-growth forest. In fact, the preserve is predominately young, dense forests that for many decades were heavily harvested for timber. In 2006, we launched the audacious goal of conserving and restoring the ecological integrity of these former industrial forest lands.

At the time, moving from the protection of small preserves to entire watersheds and diving headlong into active forest management was a huge step for The Conservancy. The best available science suggested that forest thinning (logging!) and repair or decommissioning of forest roads would be important tools to aid recovery of coastal watersheds and restore old-growth habitats. However, across the Pacific Northwest coast, there were few examples of full-bore ecological restoration at such a scale. Our Ellsworth experiment applied a rigorous design and an extensive monitoring network to test and evaluate the best approach. Before the first forest treatments began, we conducted detailed measurements of forest structure and vegetation, birds and amphibians and stream habitats to establish a baseline.

Often we describe science as “cutting edge.” This might make it seem that data, the fundamental building block of science, have a limited lifespan and easily spoil if left too long on the counter. Sometimes this is true. But when science is done well, using experiments designed for the long haul, data are more like fine wines that get better with age. Do our original 10-year-old measurements from Ellsworth still have value? Absolutely. Ecosystems change slowly, and our pre-treatment data are just now ready to pair with updated findings on the state of the preserve today.

This will allow us to start answering the fundamental questions of the Ellsworth experiment. But we need to identify creative collaborations and funding opportunities to ensure a return on our investments in healthy forests (consider donating to help continue this work). Through outreach and an open invitation to the science and conservation communities, we hope to foster an extended shelf life for our data. The insights yet to be revealed have the potential to inform future forest restoration within and beyond Ellsworth.

As we concluded the Ellsworth science tour in the early December twilight, our boots were heavy with mud but our spirits were buoyant and enthusiasm was high. The pre-treatment data provide a tremendous foundation. New technologies are emerging to aid in our efforts and exciting new partnerships are on the horizon. The second decade of science at Ellsworth is looking very promising.

Read more about the Ellsworth experiment

Here come the Chum!

Written and photographed by Dave Ryan, Field Forester

On Thursday, October 20th four hopeful adventurers wended their way down to Ellsworth “Beach”, that small, rocky shore at the terminus of our old growth trail. The hope was that the recent rains and some applied positive mental attitude could summon the Chum salmon to make their annual run up Ellsworth Creek that day. Alas, our intrepid adventurers found no salmon that day; although a walk in the forests of Ellsworth is never wasted.

On Friday, October 21st a sole wanderer ventured back to the beach and welcome to Ellsworth Creek Chum Run 2016! At some point in the intervening 24 hours, the salmon made their push several miles up Ellsworth Creek. It is always a powerful experience seeing a salmon run; whether in Alaska, The Bonneville Dam fish ladders, at Klickitat Falls, or anywhere else in the world. However, there is a solitude, a solace, and an intimacy to the Ellsworth Creek Chum run that is especially powerful to me. Perhaps it is due to, rather than in spite of, the small scale. It is a favorite time of year in what is one of my favorite places in the world.

View the photo slideshow above to see the impressive chum run!

Learn more about Preserves like Ellsworth

From Trees to Seas: Marine Team Visit Ellsworth Creek

Written and photographed by Claire Dawson, Hershman Marine Policy Fellow

On our way to the Marine Resource Committee Summit in Long Beach, Washington, several members of the Marine Team here at The Nature Conservancy got the chance to visit forester, Dave Ryan, at Ellsworth Creek Nature Preserve. This 7,600 acre preserve encompasses an entire watershed, and links with the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge. Together these provide more than 15,000 acres of refuge to species like nesting marbled murrelets, cougar, black bears, elk, amphibians, and salmon.

Our visit began with a tour of the recent log jams that have been installed upstream on Ellsworth Creek. These jams, while appearing to be no more than piles of brush and logs thrown haphazardly across a stream, are in fact an important natural feature of creeks and rivers. For decades, woody debris was removed from rivers and streams to promote navigation, recreation and beautify river beds. However, recent research has shown us that removing debris is detrimental to fish habitat. Recent creek restoration efforts have therefore focused on rebuilding these essential features.

By forcing the water over, under and around them, log jams slow the water and allow historical flood plains around creeks and rivers to fill and pool with water, providing a more favorable environment for returning adult salmon and growing fry. Slowing water flow also allows the deposit of larger sediment like rocks and rubble further upstream, creating the habitat needed for salmon to build redds and lay their eggs. These newly established woody areas also lower stream temperature by providing shaded environments, and somewhere to hide. Properly engineered, they also serve to reinforce creek beds, preventing erosion.

The Ellsworth Creek Preserve also encompasses an area of old growth Sitka spruce and Western red cedar. Following a one-mile trail down into the valley, we walked among giants, some over 800 years old to what’s known as Ellsworth Beach. With the recent rains and cooler weather, the group had hoped to see that the Chum had arrived in this part of the creek. Alas, the Chum prefer to arrive in solitude, and waited until the following day to show up in droves.

Our visit to Ellsworth served as a wonderful reminder of the interconnectedness of nature – and the various elements that work together to create habitat that is ‘just right’ for some of our region’s most beloved species. Conservation progress has implications far beyond the lands we walk on, and progress made on land has rippling effects all the way out to the deep blue sea.

Visit Ellsworth Creek Preserve

Pleasantly Prickly

Written & Photographed by David Ryan, Field Forester, Willapa Bay

Earlier this month I was scouting a project that we are planning with our Willapa NWR partners when I came across this prickly fellow. Porcupines are relatively common denizens of forests across America. Historically, many states across the nation paid bounties for these slow moving rodents. However, this one had no qualms about walking right up to me and placing his nose on my toes to determine whatever it is that porcupines need to know about human feet. After a few minutes’ assessment, it learned what it needed to about my feet and went back to the more important business of munching vegetation.

The common name of the porcupine is derived from the Latin porcus, pig, and spina, quill or spine;essentially meaning quill pig. A common myth is that porcupines can “shoot” their barbed quills at potential predators. This is untrue and the quills only become problems for those intrepid and foolish enough to actually make contact with the porcupine. The defense mechanism is so effective that porcupine have few predators. Although bobcat, cougar, coyote, wolf, or other predator may attempt to make a meal of our rodent friend, the repercussions are severe enough that few make a second attempt. Although some stubborn domestic canines refuse to learn the lesson the primary consistent and persistent predators are fishers and humans.

Why would states pay for exterminating these docile creatures? Since the inner bark of trees proves to be an important food source for porcupines, especially in winter, many forest managers sought to eliminate these rodents in an effort to reduce porcupine induced tree damage. In the early and middle 20th century, bounties were paid by the nose, ears, or feet as proof of a porcupine kill. Depending on the area, bounties were about 25 to 75 cents per porcupine. By the 1980’s porcupine bounties had largely ceased throughout the country. Not for any ecological or humanitarian reason; they were deemed to be an ineffective policy since they amounted to a subsidy of activities which some people were already doing and the fee was not high enough to induce more people to hunt more porcupine.

At Ellsworth Creek Preserve, porcupines are accepted on the landscape. And based on this encounter, I look forward to another meeting … as long as I don’t have my dog with me.

Forest Restoration Spotlight

Photographed by Chris Crisman

Restoring our forests, streams and all the habitat in between.

Our work making Washington’s forests and streams healthier is spotlighted in two vastly different landscapes – the temperate coastal rainforest of Ellsworth Creek, and the dry ponderosa forests of the Central Cascades.

These two stories highlight the restoration work taking place on the ground, as well as paint a picture of the long term vision for these very special places.

From the Chinook Observer, a beautiful story that captures the breadth and depth of the work we’re doing in Ellsworth Creek. Link below.

Chinook Observer - Towering Titans: Nature Conservancy Restoration Breathes Life Into Forest Stream

And a front page spread on the Yakima Herald that showcases our work with the Yakama Nation on the North Fork Taneum Creek. Link below.

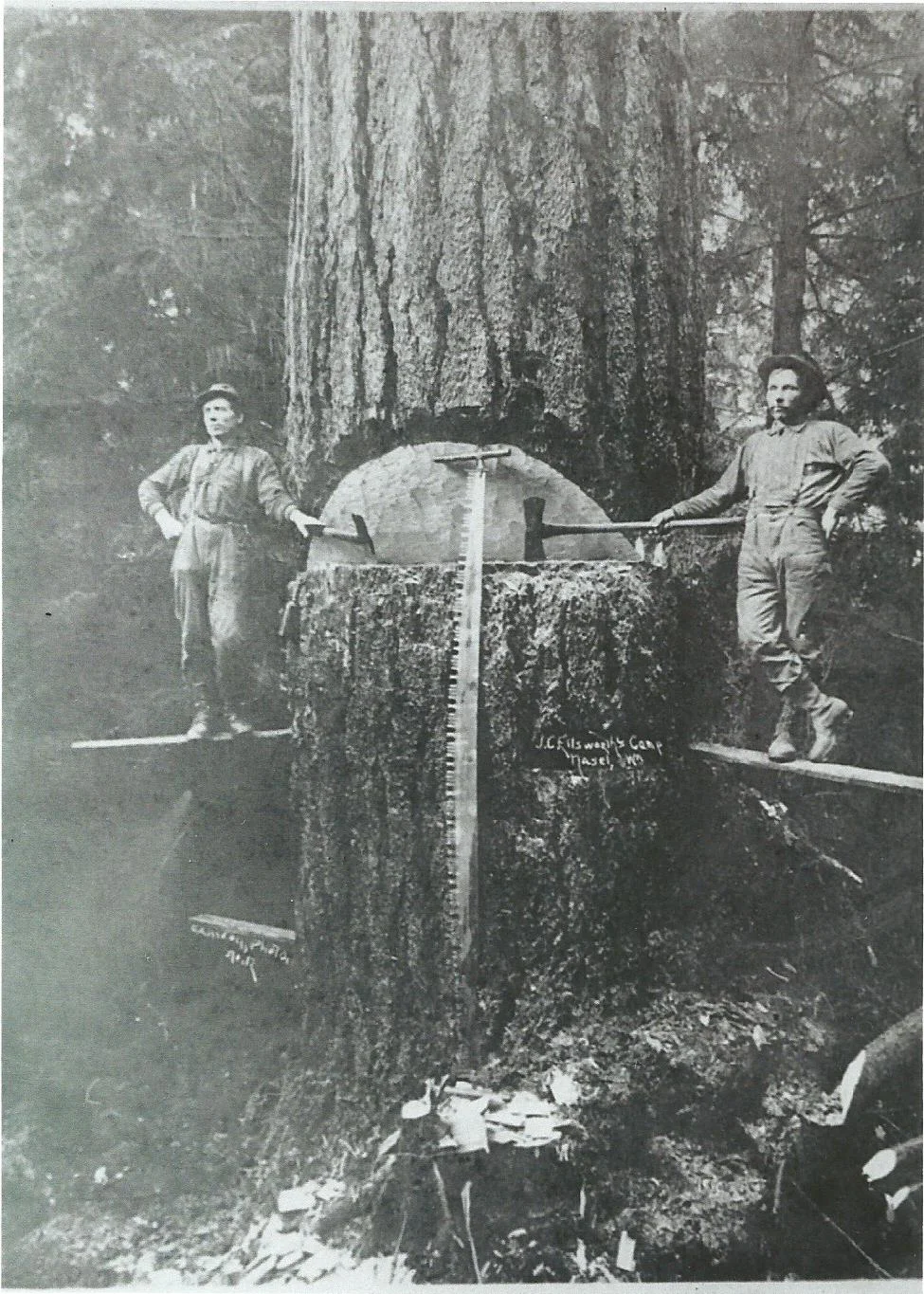

Unmaking and Remaking History

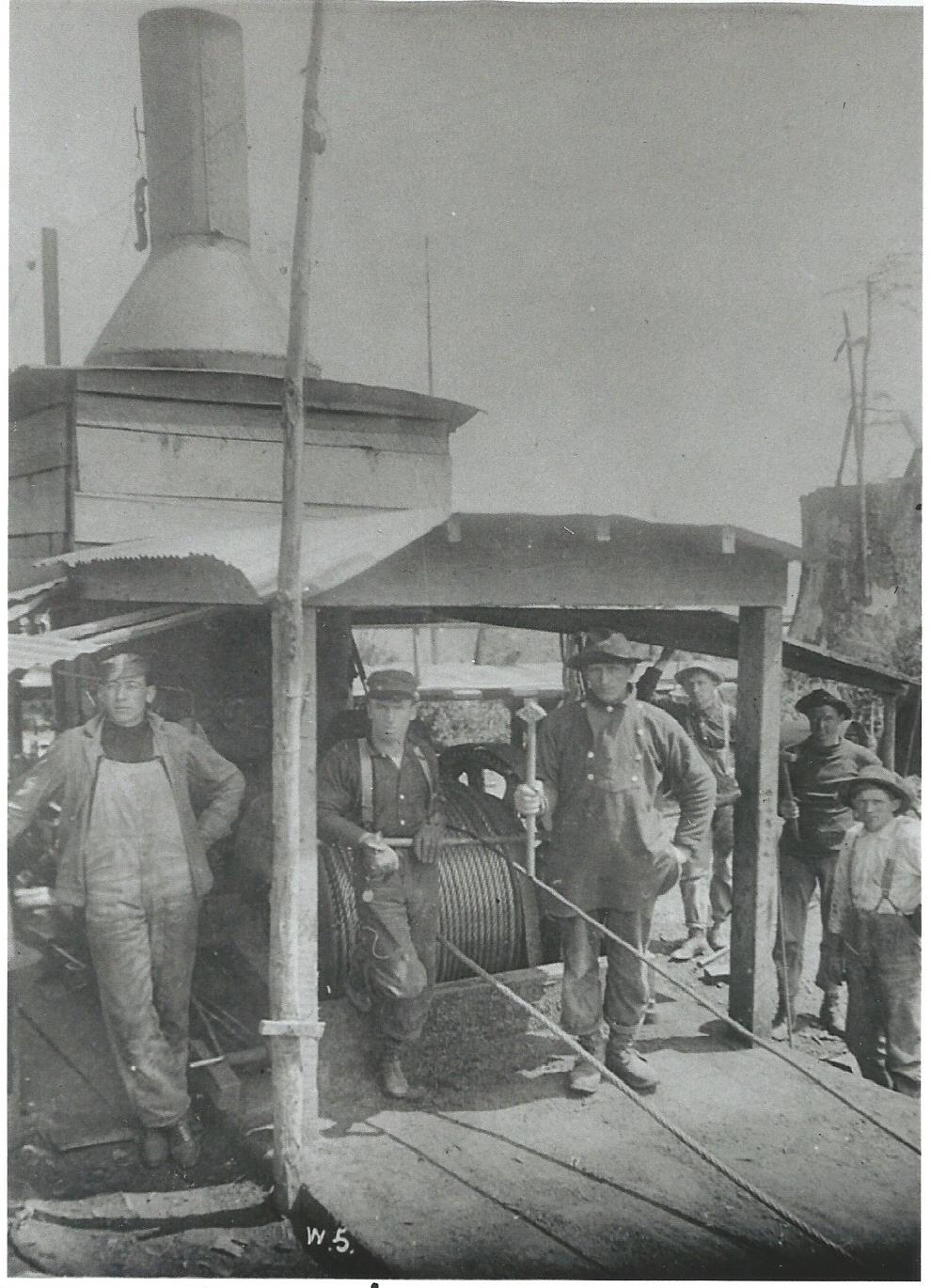

Written & Photographed by David Ryan, Field Forester; Kyle Smith, Washington Forest Restoration Manager

In the early 1940’s a cedar tree standing in the Ellsworth Creek watershed and measuring approximately 6 feet in diameter was felled by loggers from the Brix Logging Company. The bottom 110 feet of that tree was bucked into two 55 foot lengths and laid parallel on either side of Ellsworth Creek. Those two pieces formed the foundation for a bridge that spanned the creek until July 2016 when The Nature Conservancy, with the help of Ohrberg Excavation, removed that bridge, used the timbers to enhance stream structure, and restored the stream banks in an effort to improve our freshwater ecosystems and salmon habitat.

It was with mixed feelings that I watched this bridge retire from service. The design and materials were simple, efficient, and obviously effective. It was a tribute to ingenuity. Removing this bridge was necessary for many reasons; the environmental benefits are undeniable and, after over seven decades, its utility and integrity were eroding. Retiring this bridge from service supporting logging helps us to once again recruit Ellsworth Creek into service supporting salmon. But its history, and remembrance, are important. Not only was the bridge used to haul logs and loggers for almost 80 years, it was a remnant and a reminder of the history of the Pacific Northwest, of the men and women who resolutely toiled under arduous circumstances to help build this country. For better and for worse, these people worked the land and shaped it into what it is today. While some may debate about the logging history of the Pacific Northwest and the legacy that it left, I cannot dismiss the value of people who worked so hard under perilous conditions to achieve such monumental feats.

That same spirit and innovation, combined with modern machinery and technology, was apparent as the Ohrberg crew expertly removed the bridge, rebuilt the natural historic gradients, and decommissioned the road approaches as we unmade the human history and remade the natural history of Ellsworth Creek. The large diameter cedar that was used to make the bridge was returned to Ellsworth Creek in the form of a new log jam designed to foster salmon habitat. Given historic logging practices and “stream cleaning” activities from years past, it is unusual to be able to contribute wood of this size and type back into the system. When the work was completed my feelings were no longer mixed. Working with the crew, I experienced the same stalwart work ethic of those who built the bridge long ago; and I felt the absolute joy of seeing the namesake creek of this preserve take another positive step in our restoration goals.

At Ellsworth Creek Preserve we are striving to maintain and restore the forests and waters, we are striving to stay true to the natural history of the Willapa Hills. So that when salmon at sea answer the primordial call and resolutely undertake their own monumental feat of returning home to spawn, the home they return to looks like that of their ancestors who answered the same call long before there were roads and bridges in the neighborhood.