Photographed by Chris Crisman

Restoring our forests, streams and all the habitat in between.

Our work making Washington’s forests and streams healthier is spotlighted in two vastly different landscapes – the temperate coastal rainforest of Ellsworth Creek, and the dry ponderosa forests of the Central Cascades.

These two stories highlight the restoration work taking place on the ground, as well as paint a picture of the long term vision for these very special places.

From the Chinook Observer, a beautiful story that captures the breadth and depth of the work we’re doing in Ellsworth Creek. Link below.

Chinook Observer - Towering Titans: Nature Conservancy Restoration Breathes Life Into Forest Stream

And a front page spread on the Yakima Herald that showcases our work with the Yakama Nation on the North Fork Taneum Creek. Link below.

New research identifies how forest conditions interact with snowpack in the Cascades Mountain range in Washington State. Focused on the drier eastern slopes, this research informs forest restoration strategies that both protect water supplies and reduce wildfire risk.

New research out of the Ellsworth Creek Preserve offers insights into how we can accelerate the development of the old-growth traits that help forests persevere through the most severe impacts of climate change.

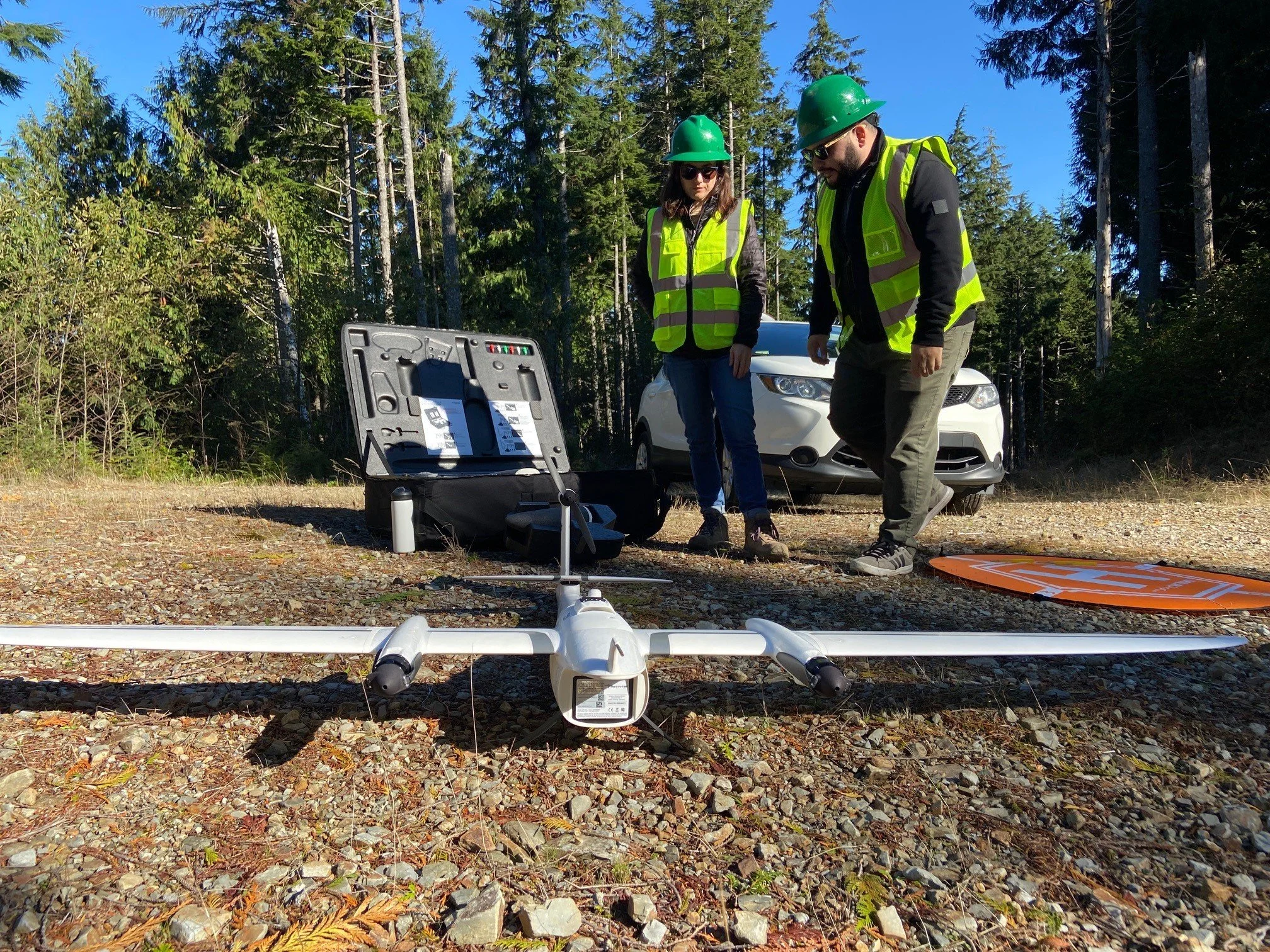

Drones have emerged as a groundbreaking tool extending our reach beyond the limits of human exploration. While many are familiar with seeing the possibilities in adventure photography or package delivery, the use of drones in conservation has become increasingly creative for those both out in the field and in the lab.

Nature Conservancy and University of Washington researchers are monitoring seedling growth and mortality along with local climate to evaluate climate resilience in the face of a changing climate at Ellsworth Creek Preserve.

The 2023 Legislative Session in Olympia saw some major achievements for nature and people: investments in improving air quality, natural climate solutions, curbing greenhouse gas emissions, and better long-term resiliency planning. A big thanks to our staff who dedicated their efforts to our priorities.

Passing a budget is one of the most important roles the State Legislature plays, as it determines how policies will be implemented and reflects what we value as a state. Our team dug into the details to see how our priorities are faring so far.

The 2023 legislative session is half-way complete - let’s check in on our priority bills, and what’s left to come.

In addition to building on the progress of the last few years, the 2023 state legislative session presents a momentous opportunity to invest in nature and people with the 2023-25 biennial budget.

Members of our all-volunteer Board of Trustees trekked to Virtual Olympia for an action-packed day of discussing our legislative priorities. It’s more exciting than it sounds!

Speak up for forests, trees and the people who depend on them by urging your legislators to support the Keep Washington Evergreen proposal this session.