Written by Beth Geiger, Northwest Writer

Graphics by Erica Simek-Sloniker, Visual Communications

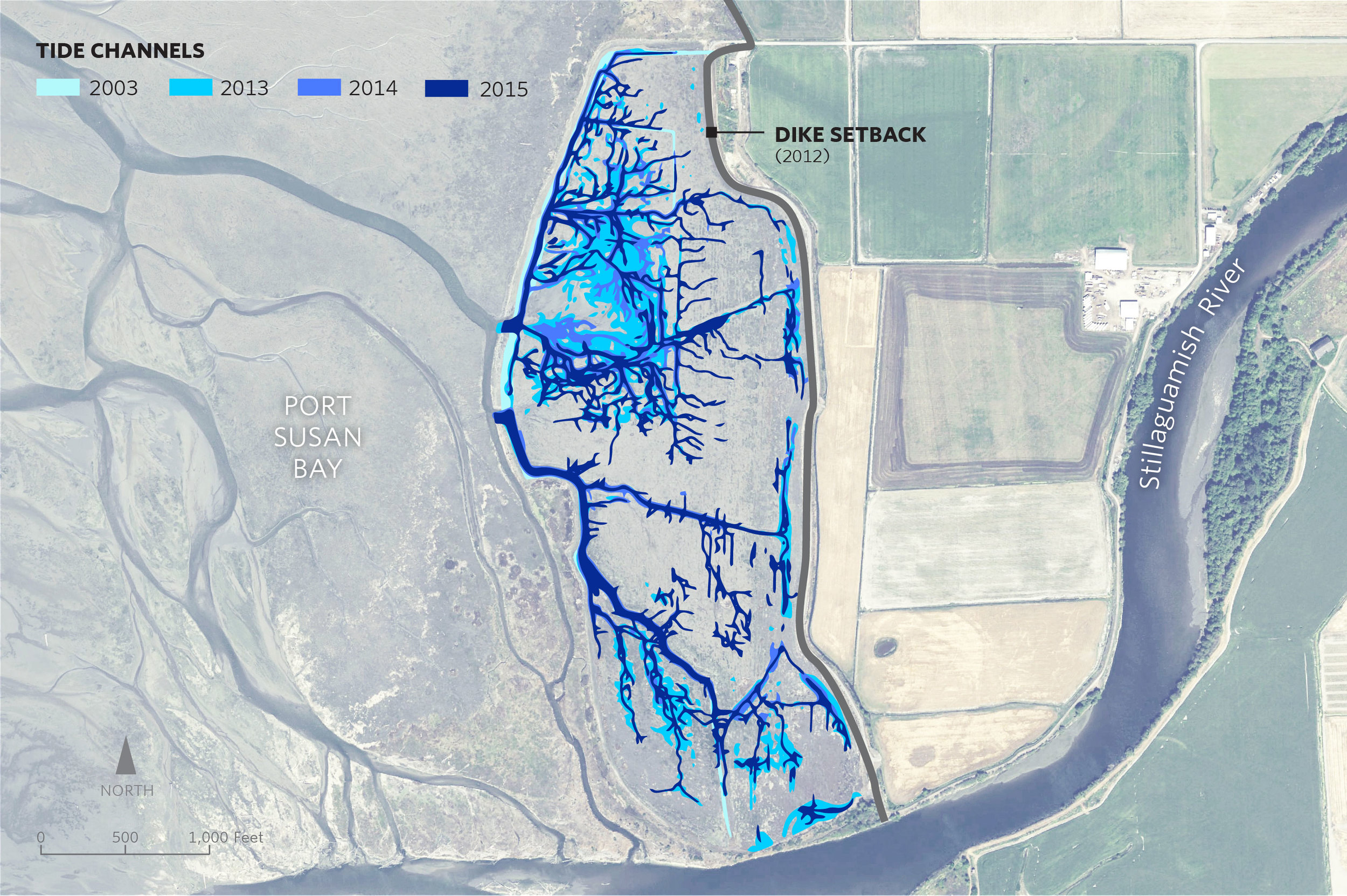

A dramatic change has taken place in a marsh in Port Susan Bay, near Stanwood, Washington. In just three years the total length of tidal channels naturally increased tenfold, from 2,300 to 23,000 meters.

Tidal channels are key to a well-functioning estuarine ecosystem. Channels increase habitat diversity, which in turn increases species diversity. Juvenile salmon use the channels, dabbling ducks use them, and invertebrates that provide food for other species use them.

Scientists like Roger Fuller, an ecosystems ecologist at Western Washington University, are chronicling the new tidal channels, along with other changes here. Fuller says the development of so many new channels is “a big surprise.”

Marsh Revival

The new channels started forming in 2012, after The Nature Conservancy removed 7,000 feet of dike that had separated the 150-acre marsh from the rest of Port Susan Bay since the 1950s. The dike removed had over time diverted Hatt Slough, the Stillaguamish River’s biggest distributary channel, south where it spills into Port Susan Bay. That dike had also cut the marsh off from its main source of fresh water and sediment.

With marsh, river, and Puget Sound connected again, natural processes took over. Critical estuary habitat quickly began to be rebuilt. A natural revival was underway.

The channels are a big part of this revival. “Channels build connections, creating the intimate links that tie the marsh, tide and river together,” Fuller explains. “They serve as the trade routes of the estuary, funneling water, sediment, fish, and the organic matter that fuels the entire estuarine food web back and forth between marsh and tidal flat.”

Sound Science

Supported by the Conservancy, Fuller and other scientists including Greg Hood with the Skagit River System Cooperative, and Eric Grossman, Christopher A. Curran and Isa Woo from the United States Geological Survey have been studying the channels and other ways that this estuary is recovering.

The researchers analyze before and after data, and compare the restoration area to a nearby reference marsh which has never been diked. They measure suspended sediment, water temperature, salinity, current, as well as topographic and ecological changes.

New tidal channels aren’t the only “before and after” they’ve seen. When the dikes were in place, the area inside them had been starved of its natural influx of sediment from the Stillaguamish River. The estuary had subsided until it was a meter lower than the surrounding tidelands in some places. It functioned more like a pond than a dynamic estuary. For example, there was no access or protected estuarine habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon transitioning from the Stillaguamish River into Puget Sound.

With the dike removed scientists have recorded a measurable rise in the height of the marsh. During those years the sediment delivered to PSB was unusually high in part due to the March 2014 Oso landslide. However, the data suggest that even if the marsh gets half as much sediment in future years, it may still rise fast enough to keep up with the rising sea level, estimated to be an average of about 24 inches by 2100.

Lessons from Nature

Fuller says that being surprised by nature here isn’t all that unexpected. “The one thing I knew before the restoration was that I would be surprised by the changes triggered by the restoration,” he says. “There's been so little research on restoration in northwest estuaries that I knew it would be really interesting to watch it unfold.”

The restoration project is part of the Port Susan Bay Preserve, which includes 4,122 acres of estuary that the Conservancy acquired in 2001. The science being conducted here reaches much further than the Preserve itself. Along with learning new lessons, we are applying scientific concepts and models honed under this and other Conservancy projects such as Fisher Slough.

Together, these projects demonstrate that carefully planned restoration can have complementary, not conflicting, benefits for people, salmon, farms, and wildlife. The Conservancy-led Floodplains by Design provides the partnerships and funding that ensure these lessons can extend to restoration projects all over Puget Sound.

As a result of diligent science and critical partnerships like this, we are learning how to make Puget Sound more resilient as climate changes, and sea level rises.